(I’ll declare my hand: back when my 2008 History Today article on the early history of the telescope came out, Enrique Joven very kindly translated it into Spanish for the magazine Astronomia, so I know Enrique pretty well. That said, Cipher Mysteries reviews don’t have star ratings & I’m not one to hide what I’m thinking, so this connection shouldn’t affect the following in any significant way.)

A thing I hear again and again from Cipher Mysteries readers is that they just aren’t into buying novels: for the most part, they’re non-fiction addicts hooked on the subtle adrenaline rush of research and who mostly feel bemused (and possibly even slightly alienated) by my fiction reviews. What, they say, can we possibly learn from a novel?

My angle on Voynich novels has never really been that of a lit crit: which is possibly just as well, it ought to be said, because most are little more than medium-boiled airport novels. Rather, I’m interested in how the idea of the Voynich Manuscript (and/or other historical cipher mysteries) is perceived and passed on by non-Voynich-researchers. Do novelists and/or their research assistants just read the Wikipedia page and make up the rest (as per the basic ‘lazy writer’ stereotype), or do some of them actually engage with the VMs, with the messy Voynich research process, and perhaps even – shock horror – with the historical evidence?

To be honest, few VMs novelists give the impression of their even having reached halfway through the Wikipedia page (however understandable that is), while a surprising number give a strong impression of having relied on even less helpful VMs information sources (such as “The Friar and the Cipher”, ugh). Even in this glorious era of Internet research, the ancient ‘GIGO’ rule (“Garbage In, Garbage Out”) works the same as it ever did. *sigh*

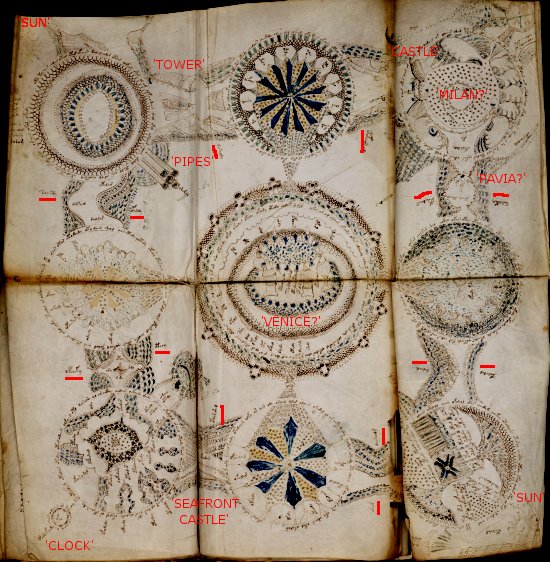

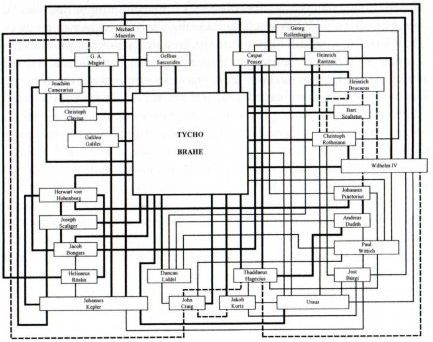

Yet Enrique Joven falls squarely into the engagement camp with his novel “The Book of God and Physics: A Novel of the Voynich Mystery”, in that he has plainly done a lot of reading on the subject and is even well aware of the Voynich mailing list. His fictional treatment of the Voynich mystery is also pretty much the first one I’ve read that treats Jesuits in a fairly sensible, non-tokenistic way (doubly impressive given that his protagonist is a teacher at a Jesuit school), and he constructs his narrative around the VMs’ thrice-APODed page f67r1 and the astronomical sparks showered over the Imperial Court by the tense relationship between Brahe and Kepler (a subject I happen to know a fair amount about).

Yet curiously, the limitations of Enrique’s book arise not from the cipher or from the history, but instead from his treatment of those (fictional) Voynich mailing list members his protagonist gets caught up up with, many of whom apparently suffer from multiple-(virtual)-personality disorder. Now, I’m no great fan of the Voynich mailing list as it has become (has any genuinely useful research appeared there in several years? I don’t think so), and it is true that some listmembers post under deliberately false or whimsical names, as if they were secretly emo teenagers. But to make this aspect so central to the story has all the feeling of a false modern mythology, a kind of ‘Hollywood Internet’ where Everyone (apart from the straight-as-a-die protagonist) Is Online In Order To Hide Some Important Aspect Of Themselves That Will Be Revealed Later In The Plot.

That aside, Joven writes pretty well – and it was a pleasure to read a Voynich book where the Long-Hidden Secret Power It Contains is in fact not About To Destroy The World As We Know It, where the main character is not a charmlessly bionic version of Anthony Grafton, and where there are neither hordes of competing three-letter-agencies nor quasi-mystical Church-backed Conspiracies all fighting each other for ownership of the VMs’ boringly heretical secret.

Long-time (if not actually long-suffering) Cipher Mysteries readers may possibly point to my high opinion of Matt Rubinstein’s Vellum and Lev Grossman’s Codex (both of which have much the same kind of ambitions and restrained execution as Enrique’s book) as correlative evidence that I’m down on Voynich airport novels: but actually, given that Max McCoy’s “Indiana Jones and the Philosopher’s Stone” is still firmly my #1 (why don’t Voynich novelists ever read this first?) on the Big Fat List, it really is all a matter of personal taste. OK, I still think Enrique’s publishers should have dug deep inside themselves to find the sense to keep the rather nice original Spanish title “The Castle of the Stars” (which actually chimes nicely with the story on many different levels, while also being pleasantly reminiscent of the linguistic hack “The astronomer married a star”), but then again it is what it is, and perhaps a clunky title alone isn’t enough to make or break a book these days.

One slightly odd coincidence is that just about the time that the paperback version came out recently, an entirely new Voynich theory came out (courtesy of P. Han) linking Tycho Brahe and historical supernovae to the VMs by way of China (but more on that another day). All of which just goes to show that there really is, errrm, nothing new under the sun, and that the boundary between historical hypothesis and fictional supposition can be surprisingly thin!