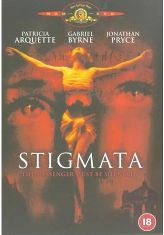

The film Stigmata (1999) presses a whole lot of my buttons. At the time it was originally released, I had been researching my own novel built on broadly the same premise: a globetrotting protagonist hunting down miraculous statues and people claiming to have duplicates of Christ’s stigmata (though that’s basically where the similarities ended). And so I was fascinated to see how the film-makers went about bringing this to life.

Even though the story and script (by Tom Lazarus, the not-quite-so-famous brother of Paul Lazarus III, director of Westworld & Capricorn One) didn’t itself think far out of the [confession] box, something magical happened in the art direction and cinematography: the use of colour, focus, light, time, sets, costume, and even make-up were all exemplary. For me, watching Stigmata was at times like being artfully collaged to death, machine-gunned with photographically (and geometrically) perfect moments: a tick on a piece of paper, Patricia Arquette lying underwater, a blood drop in a pool, blood being drawn, a blood centrifuge – all elegant, spare, swift, and focused. I highly recommend the film to anyone purely to enjoy its five-star visual treatment.

As a writer myself, however, I think the film’s problems stemmed right from the initial plotting – basically, having a priest-scientist (Gabriel Byrne) investigate the stigmata being suffered by a young atheist-hairdresser (Patricia Arquette) beneath a Vatican conspiracy managed by his control-freak boss (Jonathan Pryce) never worked as a setup for me… all too staged / stagey. The walls between the characters stopped the emotional side of the film from developing in a satisfactory way: I also didn’t much like the St Francis of Assisi (arguably the most famous stigmatic?) resolution, but you’d have to see that for yourself to see if you agree or disagree.

Watching this film a decade on, it feels a bit dated: could it be that the Da Vinci Code (and its flood of [make]-me-[rich]-too ripoffs) made the whole notion of devastating-secrets-that-would-topple-the-Church-were-they-to-be-made-public seem lightweight? And I kept wondering: was Holy Blood Holy Grail ultimately to blame?

Regardless, the film set me thinking about the kind of ur-story towards which Tom Lazarus was reaching, with his ancient Aramaic codex (based loosely on the Coptic Nag Hammadi Gospel of Thomas) triggering high-stakes factional infighting within the Vatican, with the supernatural subtext that The Truth Will Out (even beyond death).

Yes, it’s undoubtedly a cliché: and the overarching literary / cultural template at play is pretty easy to sketch out:-

- concealed message left by an ancient (implicitly perfected) person, that requires…

- deciphering and translation by (extremely proficient) domain experts, to expose…

- long-held lies behind contemporary doctrinal messages, which are supported by…

- powerful present-day conspiracies trying to maintain the (morally untenable) status quo.

Historically, does this sound familiar? After all, it is not vastly different to the entire back-story of the Renaissance (particularly during the Quattrocento). There, you had people scouring the known world for lost or concealed messages left by the Greco-Roman civilizations, to be deciphered by humanist scholars for their presumed wise (and frequently contrarian) messages.

And so I would argue that HBHG-style searches for enciphered traces of a ‘real Jesus’ are arguably little more than back-projecting our present-day cultural insecurities onto early Renaissance cultural insecurities – their search for lost classical wisdom was no different. One irony, though, is that things like the Turin Shroud (which I blogged about here and here) offer us glimpses of an entirely parallel kind of lost Christian history, far beyond the conceptual reaches of most contemporary conspiracy theorists.

What I personally fail to understand, though, is how this whole wonky ‘enciphered anti-doctrinal message’ meme has managed to endure the centuries as a literary conceit. Even my new best friend François Rabelais satirized this none too subtly in Chapter 1 of Book 1 of his alcohol-obsessed Gargantua and Pantagruel:

The diggers struck with their picks against a great tomb of bronze… Opening the tomb at a certain place which was sealed on the top with the sign of a goblet, around which was inscribed in Etruscan letters, HIC BIBITUR, they found nine flagons, arranged after the fashion of skittles in Gascony; and beneath the middle flagon lay a great, greasy, grand, pretty, little, mouldy book, which smelt more strongly but not more sweetly than roses.

Rabelais goes on to offer (“with much help from my spectacles“) his translation of the “Corrective Conundrums” found in that stinky little tome, all of them nonsensical and presumably meant to resemble some kind of vaguely prophetic quatrain-based literary genre popular in France at the time (Nostradamus fans, take note):-

The year will come, marked with a Turkish bow,

And spindles five and the bottoms of three pots, […]

This age of hocus-pocus shall go on

Until the time when Mars is put in chains

So… even though this concealed-text plot pattern was a hoary old chestnut by 1530, can anyone really explain to me how come it continues to drive a low-brow literary industry nearly five centuries later? For me, the big mystery here centres on the apparent lack of cultural progress: does Dan Brown’s success actually prove that we have learnt practically nothing in half a millennium?

Consider that your cipher mystery for the day… 🙂