It’s a nice historical detective story, one kicked off by John Dee, Frances Yates‘ favourite Elizabethan ‘magus’ (though I personally suspect Dee’s ‘magic’ was probably less ‘magickal’ than it might appear), when he claimed to have told an angel that his “great and long desyre hath byn to be hable to read those tables of Soyga“. Dee lost his precious copy of the “Book of Soyga” (but then managed to find it again): when subsequently Elias Ashmole owned it, he noted that its incipit (starting words) was “Aldaraia sive Soyga vocor…“.

However, since Ashmole’s day it was thought to have joined the serried, densely-stacked ranks of long-disappeared books and manuscripts, in the “blue-tinted gloom” of some mythical, subterranean library not unlike the “Cemetery of Lost Books” in Carlos Ruiz Zafon’s novel “The Shadow of the Wind” (2004)…

Fast-forward 400 years to 1994, and what do you know? Just like rush hour buses, two copies of the “Book of Soyga” turn up at once, both found by Deborah Harkness. Rather than searching for “Soyga“, she searched for its “Aldaraia…” incipit: which is, of course, what you were supposed to do (in the bad old days before the Internet).

It is a strange, transitional document, neither properly medieval (the text has few references to authority) nor properly Renaissance. There are some mysterious books referenced, such as the Liber Sipal and the Liber Munob: readers of my book “The Curse of the Voynich” may recognize these as simple back-to-front anagrams (Sipal = Lapis [stone], Munob = Bonum [Good], Retap Retson = Pater Noster [our Father]). In fact, Soyga itself is Agyos [saint] backwards.

But what was the secret hidden behind the 36 mysterious “tables of Soyga” that had vexed John Dee so? 36×36 square grids filled with oddly patterned letters, they look like some kind of unknown cryptographic structure. Might they hold a big secret, or might they (like many of Trithemius’ concealed texts) just be nonsense, a succession of quick brown foxes endlessly jumping over lazy dogs?

- oyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoy

rkfaqtyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyo

rxxqnkoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoy

azzsxbqtyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyo

sheimasddtguoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoy

eyuaoiismspkfaqtyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyo

enlxflfudzrxxqnkoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoy

sxcahqczfbtfzsxbqtyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyo

azepxhheurgmyknqnkoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoy

rlbriyzycuyddpotxbqtyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyo

ryrezabirhdiszeknqnkoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoy

ogzgfceztqalpntsxhssyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyo

opnxxsnodxqhuekknykkoyoyoyoyoyoyoyoy

rcqsfueesfsqrqgqrossyoyoyoyoyoyoyoyo

roauxmdkkxkhyhmpzqphdtgtguoyoyoyoyoy

aqxmudiamubkoqifbszktdmspkfaqtyoyoyo

sazoesrmlrnaqnzhgabmsmlpeahfsddtguoy

………………………………

(etc)

Jim Reeds, one of the great historical code-breakers of modern times, stepped forward unto the breach to see what he could make of these strange tables: he transcribed them, ran a few tests, and (thank heavens) worked out the three-stage algorithm with which they were generated.

Stage 1: fill in the 36-high left-hand column (which I’ve highlighted in blue above) with a six-letter codeword (such as ‘orrase‘ for table #5, ‘Leo’) followed by its reverse anagram (‘esarro‘), and then repeat them both two more times

Stage 2: fill each of the 35 remaining elements in the top line in turn with ((W + f(W)) modulo 23), where W = the element to the West, ie the preceding element. The basic letter numbering is straightforward (a = 1, b = 2, c = 3, … u = 20, x = 21, y = 22, and z = 23), but the funny f(W) function is a bit arbitrary and strange:-

- x f(x) x f(x) x f(x) x f(x)

a…2, g…6, n..14, t…8

b…2, h…5, o…8, u..15

c…3, i..14, p..13, x..15

d…5, k..15, q..20, y..15

e..14, l..20, r..11, z…2

f…2, m..22, s…8

Stage 3: fill each row in turn with ((N + f(W)) modulo 23), where N = the element to the North, ie the element above the current element.

For example, if you try Stage 2 out on ‘o’, (W + f(W)) modulo 23 = (14 + 8) modulo 23 = 22 = ‘y’, while (22 + 15) modulo 23 = 14 = ‘o’, which is why you get all the “yoyo”s in the table above.

And there (bar the inevitable miscalculations of something so darn fiddly, as well as all the inevitable scribal copying mistakes) you have it: the information in the Soyga tables is no more than the repeated left-hand column keyword, plus a rather wonky algorithm.

You can read Jim Reeds paper here: a full version (with diagrams) appeared in the pricy (but interesting) book John Dee: Interdisciplinary essays in English Renaissance Thought (2006). The End.

Except… where exactly did that funny f(x) table come from? Was that just, errrm, magicked out of the air? Jim Reeds never comments, never remarks, never speculates: effectively, he just says ‘here it is, this is how it is‘. But perhaps this f(x) sequence is in itself some kind of monoalphabetic or offseting cipher to hide the originator’s name: Jim is bound to have thought of this, so let’s look at it ourselves:-

- 1.2.3.4..5.6.7.8..9.10.11.12.13.14.15.16.17.18.19.20.21.22.23

2.2.3.5.14.2.6.5.14.15.20.22.14..8.13.20.11..8..8.15.15.15..2

If we discount the “2 2” at the start and the “8 8 15 15 15 2” at the end as probable padding, we can see that “14” appears three times, and “5 14” twice. Hmm: might “14” be a vowel?

- 2 3 5 14 2 6 5 14 15 20 22 14 8 13 20 11 8

- a b d n a e d n o t x n g m t k g

- b c e o b f e o p u y o h n u l h

- c d f p c g f p q x z p i o x m i

- d e g q d h g q r y a q k p y n k

- e f h r e i h r s z b r l q z o l

- f g i s f k i s t a c s m r a p m

- g h k t g l k t u b d t n s b q n

- h i l u h m l u x c e u o t c r o

- i k m x i n m x y d f x p u d s p

- k l n y k o n y z e g y q x e t q

- l m o z l p o z a f h z r y f u r

- m n p a m q p a b g i a s z g x s

- n o q b n r q b c h k b t a h y t

- o p r c o s r c d i l c u b i z u

- p q s d p t s d e k m d x c k a x

- q r t e q u t e f l n e y d l b y

- r s u f r x u f g m o f z e m c z

- s t x g s y x g h n p g a f n d a

- t u y h t z y h i o q h b g o e b

- u x z i u a z i k p r i c h p f c

- x y a k x b a k l q s k d i q g d

- y z b l y c b l m r t l e k r h e

- z a c m z d c m n s u m f l s i f

Nope, sorry: the only word-like entities here are “tondean”, “catsik”, and “zikprich”, none of which look particularly promising. This looks like a dead end… unless you happen to know better? 😉

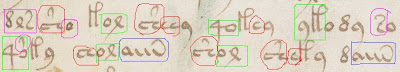

A final note. Jim remarks that one of the manuscripts has apparently been proofread, with “f[letter]” marks (ie fa, fb, fc, etc); and surmises that the “f” stands for “falso” (meaning false), with the second letter the suggested correction. What is interesting (and may not have been noted before) is that in the Voynich Manuscript, there’s a piece of marginalia that follows this same pattern. On f2v, just above the second paragraph (which starts “kchor…”) there’s a “fa” note in a darker ink. Was this a proof-reading mark by the original author (it’s in a different ink, so this is perhaps unlikely): or possibly a comment by a later code-breaker that the word / paragraph somehow seems “falso” or inconsistent? “kchor” appears quite a few times (20 or so), so both attempted explanations seem a bit odd. Something to think about, anyway…