There are many different ways of, well, reading the unreadable: what isn’t so well-known is that the technical terminology we use tends to highlight those particular aspects that we think are worthy of study (as well as to occult those aspects we are not so interested in). The big three buzzwords are:-

- Cryptography: writing hidden messages – a historical / forensic approach

- Cryptanalysis: analysing hidden messages – a statistical / analytical approach

- Cryptology: reading hidden messages – a linguistic / code-breaking approach

Generally, you’ll see these terms used extremely loosely (if not interchangeably): but that’s something of a tragedy, as each strand is concerned with a different type of discourse, a different type of truth to help us get to the end-line, that of finding out what happened.

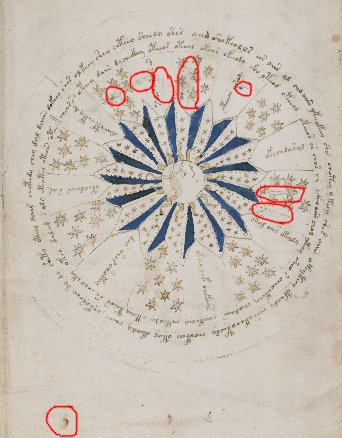

(1) If you study the cryptography of the Voynich Manuscript, you would primarily focus on issues such as: the intellectual history behind (and embedded within) the glyphs, the forensic layering of the writing itself, the physical strokes that make up the letters, what corrections there are to be found, how Voynichese practice evolved during the construction of the document, how the writing interrelates with the drawings, etc. This is reconstructive forensic history, that seeks to establish the truth of the writing system – to establish the mental structures that were given systematic shape (and yet were hidden) in the writing. In many ways, the end-product would be an accurate transcription of the text – but I strongly believe that this strand has not yet been pursued to its logical conclusion.

(2) If you study the cryptanalysis of the Voynich manuscript, you would instead take the study of the cryptography completely as a given, and use the resulting transcription as a starting point for your analytical research, however (in)accurate it may be. The argument has typically been that even if, say, 10% of the transcription is wrong, statistical analysis of the remaining 90% should still yield informative results that are (to a certain degree) illustrative of the underlying mechanisms. Yet the specific reliance upon the transcription cannot be ignored, particularly when you go hunting for larger-scale patterns (such as words, or lines). And there is a very strong case to be made that the absence of convincing statistical results to date arises not from inadequate statistical testing, but instead from some basic division within the text being misunderstood.

(3) If you study the cryptology of the Voynich Manuscript, then you would take as a given a carefully-selected set of statistical properties previously derived from cryptanalysis, and look for some kind of linguistic fit between those properties and the properties of known languages and/or transformations of known languages (such as shorthand, patois, abbreviation, contraction, etc). Many Voynich theories are based on a very naive cryptological reading, often filling the vast gaps between the two models by expanding the range of possible languages that are present all at the same time, and hence resulting in a claimed plaintext that is a hugely interpretative soup of Romance language fragments – though Leo Levitov’s “polyglot oral tongue” is a prime example, it is very far from being the only one of its kind.

In terms of this framework, I’ve invested most of my time on the VMs’ cryptography, to the point where I believe I can give an account of each of the glyphs and of the evolution of the writing system: but I’m now at the point where I have to move on to the cryptanalysis in a more focused way to make progress.

The overall point I’m trying to make is that we need to get the history (cryptography), the statistics (cryptanalysis) and the linguistics (cryptology) sorted out in order to get over the high walls of the Voynich Manuscript’s defences: its singular beauty arises from how it manages to confound all three of these approaches simultaneously. This is, I suspect, merely a byproduct of the ‘undivided’ Quattrocento thinking that gave it life – that it comes from the time-period just before we (as a culture) imposed artificial divisions on the way we think about the world… just before intellectual specialization took hold. The historian part of me wants to shout: look, it’s the product of a Renaissance Man, in every useful sense of that much-abused phrase.