Quick digression: I went into several second hand bookshops a couple of weekends ago, and while I found a few nice historical books to keep me occupied, what struck me was the complete lack of the usual breathless UFO books. In the olden days (i.e. five years ago), these used to fill the shelves, so why are they now so few and far between? Might conspiracy theorists have moved on from UFOs to (who knows?) vaccine, woke, Brexit, Russian political funding, MAGA, Trump, Jewish space lasers, American democracy, doomscrolling? Is Roswell too distant a memory for anyone but me to give a stuff about?

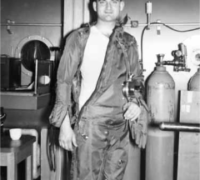

Anyway… one of the big ‘traditional’ focuses of UFO conspiracy theorists is Major Jesse Marcel. It was he who famously went to Mac Brazel’s ranch in Corona NM (near Roswell) where pieces of strange metal foil and curious beam fragments (some with odd writing on) were found. Plenty of books and documentaries have been made featuring Marcel, mainly because he combined a credible straight-down-the-line military career with his firm belief that what crashed near Roswell was, ummm, extra-terrestrial.

Yet another very similar military man went to Brazel’s ranch that day: Counter Intelligence officer Captain Sheridan Cavitt. Relatively little UFOlogical ink has been spilt on Cavitt, perhaps because he combined a credible straight-down-the-line military career with his firm belief that what crashed near Roswell was… ummm, just a balloon. Which would, of course, make for far less juicy books and tabloid headlines.

Still, it’s time to take a look at Sheridan Cavitt, the other well-known military Roswell responder…

Captain Sheridan Cavitt

Perhaps the best place to start is Nick Redfern’s two-part article on Sheridan Cavitt: here’s part one, and here’s part two. The most ‘horse’s mouth’ thing Cavitt said about Roswell was in a May 24, 1994 interview with Colonel Richard L. Weaver, USAF:

“There were no, as I understand, checkpoints or anything like that (going through guards and that sort of garbage) we went out there and we found it. It was a small amount of, as I recall, bamboo sticks, reflective sort of material that would, well at first glance, you would probably think it was aluminum foil, something of that type. And we gathered up some of it.”

As to how large that debris field was, Cavitt asserted that it was “Maybe as long as this room is wide.” And he was sure (he said) that it was “a weather balloon”.

UFO researcher Kevin Randle interviewed Cavitt in 1990: Cavitt told Randle that because in 1947 he was working for the CIC (Counter Intelligence Corps), any report he made would have gone to Washington (there’s a persistent rumour Cavitt wrote a report that has since disappeared). As far as the Roswell incident goes, Randle was sure Cavitt was lying (which he was), and Cavitt was pretty sure Marcel was lying (he probably was). At the same time, Randle pointed out that “Cavitt doesn’t even agree with Cavitt“, so we have to exercise caution when trying to make sense of all this.

But there was in fact a third Army early responder, Bill Rickett. And according to Rickett’s later testimony, it was Rickett and Cavitt who got to Brazel’s ranch first, with Rickett coming back later with Marcel. And that kind of broadly squares with Cavitt saying that he took the stuff he collected from the site with Rickett back to the base at Roswell and handed it to Marcel; and that he thought Marcel claiming that he’d gone to the site first with Cavitt was wrong, and had caused Cavitt a load of problems.

So… what did happen?

On balance, I think that the actual first Roswell responders were probably Sheridan Cavitt and Bill Rickett; and that Jesse Marcel, having been handed debris from the site by Cavitt back at the base, had then gone to the site with Bill Rickett a little later that day. Generally, even though Cavitt wasn’t a particularly reliable witness, I’m a little more comfortable with parts (though, again, not all) of Rickett’s account.

Does that mean that I think Jesse Marcel embiggened his role up in the whole affair, and should really have been recorded as third or fourth or fifth responder? Yes, probably. Really, my guess is that Marcel had told his family stories for several decades about what happened that day, and in the end wasn’t really comfortable untangling that whole knot if that meant reducing his heroic role in the story.

At the same time, Marcel was sure what had been in the field wasn’t a weather balloon, even if Cavitt was: yet if the debris resembled aluminium foil and bamboo, it can’t have had anything to do with Project Mogul, as Cavitt and others later (incorrectly) claimed. I believe they all tried to frame what they saw in terms of what they knew: but what they saw it wasn’t anything that they knew. By which I mean to imply not that it was some kind of ‘alien technology’ (because I’m sure it wasn’t): but rather non-Army technology sufficiently advanced to confuse the heck out of them both (while still not being magic).

Finally, on the matter of the mysterious “bodies” at the other site close to Roswell, Cavitt kept resolutely schtum: but that’s definitely a topic for another day (i.e. not today).

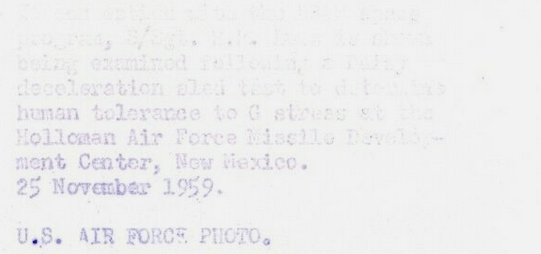

PS: here’s a nice video of Project Mogul balloons being launched, courtesy of the Black Vault. Might one of these have come down on Mac Brazel’s ranch? I really don’t think so, sorry.