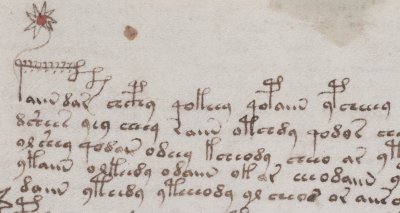

Though the Voynich Manuscript has many unusual and interesting sections, arguably the most boring of the lot is Quire 20 (‘Q20’). This comprises a thick-ish set of six text-only bifolios (though with a central bifolio missing), where just about every paragraph has a tiny drawing of a star/flower/comet shape attached to it.

Tally all these up, and you find that Q20 as it now is has between 345 and 347 stars (two are slightly questionable). This is intriguingly close enough to the magic number 365 for some researchers to have speculated that this section might actually be an almanack, i.e. a one-paragraph-per-day-of-the-year guide. It is also close enough to the similarly resonant number 360 for some (and, indeed, often the same) people to speculate whether the section might be a kind of per-degree astrology, i.e. a one-paragraph-per-degree judicial astrological reference. If neither, then the general consensus seems to be that Q20 is some kind of secret recipe / spell collection (there were plenty of these in the Middle Ages).

Yet the problem with constructing an explanation around 365 stars, as Elmar Vogt pointed out in a 2009 blog post, is that Q20 ticks over fairly consistently at about 15 paragraphs/stars per page, and we have four pages missing from the centre: hence we would expect the grand total to be somewhere closer to 345 + (15 x 4) = 405, which is far too many. Of course, the same observation holds true for 360 per-degree paragraphs too.

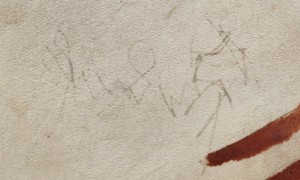

You could try – as Elmar subsequently did – to start from a count of 365 (or indeed from 360) and hold that as a constraint to generate plausible codicological starting points (i.e. by answering the question “what kind of ordering could be constructed that would be consistent with 360 or 365 starred paragraphs?”). However, you quickly run into the problem that the marginalia-filled f116v looks very much as if it was originally (as it now is) the final page of the quire, which (in my opinion) is also supported by the large, final, unstarred paragraph on f116r, [which, incidentally, I predict will turn out to hold the most informative plaintext of the whole book, i.e. stuff about the author]. And if you accept that f116 was indeed probably originally the end folio, then you run into a bit of a brick wall as far as possible shufflings of Q20 go.

All the same, here’s an interesting new angle to consider. Cipher Mysteries reader Tim Tattrie very kindly left a comment here a few days ago, pointing out that the rare EVA letter ‘x’ appears in 19 folios – “46r, 55r, 57v, 66r, 85r, 86v6, 94r, 104r, 105r, 105v, 106v, 107v [NP: actually 107r], 108r, 108v, 111r, 112r [NP: ?], 113v, 114v, 115v” – which he wondered might suggest a possible thematic link between Q8, Q14 (the nine-rosette fold-out) and Q20. However, what particularly struck me about this list of pages was that (remembering that f109 and f110 form Q20’s missing central bifolio) every folio in Q20 has an ‘x’ except for the first folio (f103) and the last folio (f116), which are of course part of the same bifolio.

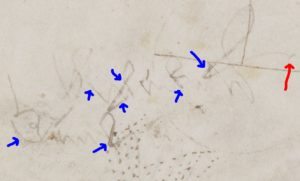

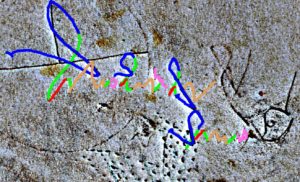

Could it be that the f103-f116 bifolio was originally separate from the rest of the Q20 bifolios? Even though f116v looks as though it really ought to be the back page of the quire, I have always found f103r a very unconvincing first page for a quire – with no introduction, no title, no ornate scribal scene-setting, to my eyes it seems more like a mid-quire page, which is a bit of a puzzle. In fact, of all the Q20 starred paragraph pages I’d have thought the strongest candidate for quire-initial page would be f105r, courtesy of its overelaborate split (and dotted, and starred) gallows, as per the below image. Just so you know, f105r also contains two of Q20’s four ‘titles’ (an offset piece of Voynichese text), one on line 10 and one on its bottom line, the latter of which crypto crib-fans may well be pleased to hear that I suspect contains the title of the chapter – “otaiir.chedaiin.otair.otaly” (note that the two other Q20 titles are to be found on f108v and f114r).

Interestingly, Tim Tattrie then pointed out that “f103 and 116 are linked as they are the only folios in Q20 that do not have tails on the stars“: which (together with the absence of ‘x’s) suggests that they were originally joined together, i.e. as the central bifolio of a quire. All of which suggests that the original layout of Q20 may have been radically different layout, with the f105/f114 bifolio on the outside of (let’s call it) ‘Q20a’ and the f103/f116 bifolio on the outside of ‘Q20b’, and all the other Q20 bifolios in the middle of Q20a.

Picking up where Elmar left off before, this is where almanack (365-star) and per-degree (360-star) proponents would somewhat enthusiastically ask how many stars this proposed Q20a gathering would have originally had. Because f103 has 35 stars, and f116 has 11 stars, Q20a has (say) 299 stars across five bifolios. Add in the missing f109/f110 bifolio, and the answer is terrifically simple: extrapolating from Q20a’s stars-per-paragraph figure, we’d expect the original quire to have had (299 * 6 / 5) = 359 stars – hence the likelihood is that Q20a contained some kind of per-degree zodiac reference, most probably along the lines of Pietro d’Abano’s per-degree astrology.

Having said that… the figures are extremely tight, and if the missing bifolio instead mimicked the f108/f111 bifolio (which, after all, it ended up physically next to in the final binding) rather than the overall section average (which may also be slightly lowered by the 11-per-page average of f105), it would have closer to 72 stars rather than 60, which would then bring the 365-star almanack hypothesis back into the frame. It’s a tricky old business this, nearly enough to drive a poor codicologist to drink (please excuse my shaking white cotton gloves, etc).

There are various other observations that might help us reconstruct what was going on with Q20a/Q20b:-

- Helpfully, Elmar documented the various empty/full star patterns on the various Q20 pages, and noted that most of them are no more than empty-full-empty-full-empty-full sequences, with the exception of “f103r, f104r and f108r”, which he interprets as implying that they were probably originally placed together.

- f105v is very much more faded than all the other pages in Q20, which I have wondered might have been the result of weathering: if f105 had been the outer folio of an unbound Q20a, then it could very well have ended up being folded around the back of Q20b by mistake for a while early in the life of the Q20 pages, which would have put it on the back page of the whole manuscript.

- I still believe that the gap in the text in the outside edge of f112 was no more than a vellum fault (probably a long vertical rip) in the page in the original (unenciphered) document from which Q20a was copied, but that’s probably not material to any bifolio nesting discussion.

- The tail-less paragraph stars on f103r seem slightly ad hoc to my eyes: I suspect that they were added in after the event.

- The notion that Q20 originally contained seven nested quires (as per the folio numbering) seems slightly over-the-top to me: this seems a bit too much for a single mid-15th century binding to comfortably take.

What are we to make of all this fairly raw stream of codicological stuff? Personally, I’m fairly sold on the idea that Q20 was originally formed of two distinct gatherings, with f105r the first page of the first gathering (Q20a) and f116v the last page of the last gathering (Q20b). Placing all the remaining bifolios in Q20a to get close to the magic numbers of 360 and 365 is a hugely seductive idea: however, such numerological arguments often seem massively convincing for a short period of time, before you kind of “sober up” to their limitations, so I think it’s probably safer to note the suggestion down as a neat explanation (but to return to it later when we have amassed more critical codicological information about the Q20 pages).

Perhaps the thing to do now is to look at other features (such as handwriting, rare symbols, letter patterns, contact transfers, etc) for extra dimensions of grouping / nesting information within the Q20 pages, and to look for more ways of testing out this proposed Q20a/Q20b split. Sorry not to be able to come to a definitive conclusion on all this in a single post, but with a bit of luck this should be a good starting point for further discussion on what Q20 originally looked like. Tim, Elmar, John, Glen (and anyone else), what do you think? 🙂

Update: having posted all the above, I went off and had a look at all the ‘x’ instances in Q20 – these seem to have a strong affinity for sitting next to ‘ar’ and ‘or’ pairs, e.g. arxor / salxor / kedarxy / oxorshey / oxar / shoxar / lxorxoiin, etc.