A grateful tip of the hat to Zodiac Killer Cipher Meister Dave Oranchak, for passing me a lovely little story in the Daily Mail (and now many other newspapers) about a plucky Second World War carrier pigeon found dead in a Surrey chimney. So far so mundane (there were 250,000 in the Royal Pigeon Service, and many failed to reach home): but what sets this particular one well apart was that it was carrying an enciphered message.

My transcription of the message looks like this (where there’s ambiguity, I’ve included the possibilities in square brackets, though I’d recommend sticking with the first of each set):-

AOAKN HVPKD FNFJ[W/U] YIDDC

RQXSR DJHFP GOVFN MIAPX

PABUZ WYYNP CMPNW HJRZH .

NLXKG MEMKK ONOIB A[K/R/H]EEQ

UAOTA . RBQRH DJOFM TPZEH

LKXGH RGGHT JRZCQ FNKTQ .

KLDTS GQIR[U/W] AOAKN 27 1525/6.

The first and last group (both “AOAKN”) almost certainly denote a key reference, a feature common to many cipher systems. The “27 1525/6” bit is probably not part of the code but a military reference of some sort – I’d predict day of current month (27th) & time of day (3.25pm). It also seems vaguely possible that the dots delimit sentences, but they could just as easily be bits of dirt. 😉 According to Geoff here, SOE started the war with poem codes (see Leo Marks’ “Between Silk And Cyanide”) moved to various double transposition systems after 1942 (Marks joined SOE in 1942), before moving to one time pads in 1943 (see Marks’ Appendix Two): so if it can be proved to be something like a Playfair cipher (as Geoff suspects from a number of repeated bigrams), a tentative date would seem to be 1942.

As for me, I’m rather taken by the poem cipher system (most famous of which was Violette Szabo’s poem: “The life that I have / Is all that I have / And the life that I have / Is yours“), which p.11 of Marks describes as:-

“An agent had to choose five words at random from his poem and give each letter of these words a number. He then used these numbers to jumble and juxtapose his clear text. To let his Home Station know which five words he had chosen, he inserted an indicator-group at the start of his message.”

Hence my guess is that “AOAKN” are the initial letters of the five words in the SOE agent’s poem which (in the early part of the war) was often by Shakespeare or even Edgar Allan Poe (though probably not “The Raven”, as no word in the first section begins with ‘K’, bah!). Furthermore, “HVPKD” could well be a nonsense five letter set (as this was one of the tricks SOE told its agents to use to improve security on what was otherwise a fairly brittle code). (Incidentally, my favourite bit of “Between Silk & Cyanide” is Chapter 20 “The Findings of the Court”, where Marks finally gets to meet his hero John Tiltman). All the same (as you’ve probably guessed), the single message was have here may well be far too small a sample to break with confidence, without some kind of historical deus ex machina to help us out. That, or a really good guess at a poem (but hopefully not the one about Charles De Gaulle). 🙂

Anyway, back to our plucky-dead-Surrey-chimney pigeon. Below the cipher section, the transmission sheet notes that two copies were sent at “1522” (presumably the time of day again), and there are also two markings:

* NURP 40 TW 194

* NURP 37 DK 76

It turns out that these are the reference numbers of the two pigeons (the dead one is the first one). Remember that thirty two pigeons were awarded the Dickin Medal (the animal version of the Victoria Cross) in WW2, so this was a serious business! Kenley Lass (NURP.36.JH.190) was one of the 32, as was Dutch Coast (NURP.41.A.2164), Commando (NURP.38.EGU.242), Royal Blue (NURP.40.GVIS.453), and Mary (NURP.40.WCE.249). Moreover, “NURP” stands for the “National Union of Racing Pigeons”, so these were all NURP-affiliated pigeons, as was the dead pigeon itself.

Interestingly, Royal Blue was a blue cock pigeon, owned by King George VI at his Royal Pigeon Lofts at Sandringham: hence “GVIS” was short for “George VI Sandringham”, while the “40” means that the pigeon was entered into the database in 1940. Hence “NURP 40 TW 194” could not have been sent before 1940, because 1940 was when its little pigeon-y war began. Also: TW would have been the reference for the pigeon’s club (perhaps Twickenham?) or individual owner. Doubtless someone at The Racing Pigeon Magazine has already worked this out, so perhaps they’re holding it back to announce at the Racing Pigeon Show in Telford on 24th November 2012, who knows? 🙂

Yet according to the New York Times, though, pigeon NURP 40 TW 194’s remains were first found in 1982 but – according to Colin Hill, Bletchley Park’s go-to-guy for pigeon history – the mystery here is that neither pigeon’s reference number appears in any pigeon archive listing. Dnn dnn daaaaah!

Other useful information: the message was addressed to “X02” (the code for Bomber Command) and the sender was apparently “W Stott Sjt”, i.e. Sergeant W. Stott, where the fact that Sergeant was written “Sjt” rather than “Sgt” may possibly imply that he was in the RAF (opinions differ on this). A quick database search yielded two good candidates: “Sergeant William Gordon Stott” (1232159 in RAF’s Volunteer Reserve 13 Squadron, died in 1942, buried in Beja War Cemetery, Tunisia) and “Sergeant William Leslie Stott” (508080 in the RAF, died in 1945 aged 35, buried in Chester’s Overleigh Cemetery).

I also found out the history of 13 Squadron:

* 1939 – Odiham, Hants

* October 1939 – Mons-en-Chausseé (mainly photographic reconaissance)

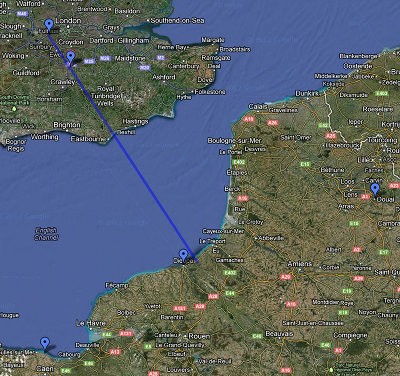

* May 1940 – Douai (bombing frontline troop positions)

* June 1940 – Hooton Park, Cheshire (anti-submarine patrols, Lincolnshire & Irish Sea)

* July 1941 – Odiham, Hants (dropping smoke screens to cover paratrooper drops & gliders)

* November 1942 – Blida, Algeria (bombing airfields and troop groupings)

* [???] 1943 – Protville II, Tunisia (shipping protection)

* October 1943 – Sidi Ahmed, then Sidi Amor

* December 1943 – Kabrit, Egypt

* September 1945 – Hassani

* April 1946 – squadron was disbanded.

The nice thing that has historians ooh-ing and aah-ing is that the kind of red Bakelite canister containing the message was apparently only used by SOE, the Special Operations Executive where Marks worked. Note that even though Stott’s name doesn’t appear on the (now-deleted) list of SOE agents on the Internet, that doesn’t really mean a lot, as it is woefully incomplete.

So… what does it say? To me, the likeliest story seems to be that it was sent by an SOE agent in Douai in early 1940, using a pair of pigeons brought there by 13 Squadron, and using just the kind of poem code Leo Marks fought hard to get rid of. Yet I can’t help wondering whether the comment left by “MrEdTheTalkingHorse” on the Daily Telegraph’s webpage is correct, and that “Perhaps it was helping von Stauffenberg plot a coo.”

PS: if you don’t believe any of this, here’s a nice picture of a RAF guy with a pigeon. Aaah.

PPS: a pigeon sketch I found online (but can’t now find a link to, sorry)

Tim Brooke-Taylor: Look, a carrier pigeon with a message tied to its leg!

John Cleese: What does it say?

TBT: It says .. “this is the leg of a carrier pigeon”.

JC: Turn it over, I think there’s something written on the back!

TBT: So there is! It says .. “this is the back of a carrier pigeon”.

JC: Is that it?

TBT: No, wait, there’s a PS!

JC: What does it say?

TBT: Pssss.

PPPS: …and of course the story has been Slashdotted already. Yes, “Drink more ovaltine” gets yet another airing by a plucky flamebaiter there. Hats off to Slashdotters!

Update: for more recent Cipher Mysteries updates to this story, there is a “ring of truth” post and a dead pigeon timeline post, with highish-resolution images of the enciphered message.