Back in 2010, I speculated that one of the oddly-unreadable lines of text on the Voynich Manuscript’s last page (f116v) might have originally read “pax + nax + vax”. Here’s a little bit more background on that mysterious phrase…

A Prague Nun’s Amulet

In “The Book of Grimoires: The Secret Grammar of Magic” (and in several other of his oddly-similar books), Claude Lecouteux mentions that:

During the restoration of the Saint George Basilica in Prague, a parchment strip requesting the cure of a case of trench fever for a certain Dobrozlava was found under the plaster of an alcove. The prayer ended with: “May Pax + nax vax be the remedy for this servant of God. Amen.”

Confirming this account is “STÄRKER ALS DER GLAUBE: MAGIE, ABERGLAUBE UND ZAUBER IN DER EPOCHE DES HUSSITISMUS” by František Šmahel (p.322, Bohemia Band 32 (1991)):

Einen nicht weniger seltenen Beleg stellt das Original eines Pergamentamuletts aus der ersten Hälfte des 14.Jahrhunderts dar, das die Schwester Dobroslawa aus dem Prager Benediktinerinnenkonvent des hl Georg vor dem Schüttelfrost bewahren sollte. Wurden die magischen Wirkungen des Textes in diesem Falle durch die Beschwörungsformel „pax-nax-vax” erhöht, so erfüllten im Milieu des einfachen Volkes einzelne Buchstaben oder auch deren bizarre Ansammlungen diese Funktion, wie wir sie z.B. auf keramischen Gefäßen finden.

…which Google Translate (slightly tweaked) turns into:

An original parchment amulet from the first half of the 14th century, which the sister Dobroslawa from the Benedictine convent of St. George in Prague was to protect against the chills, is no less rare a document. If the magic effects of the text were increased in this case by the incantation “pax-nax-vax”, in the milieu of the common people individual letters or their bizarre collections fulfilled this function, because we find them on ceramic vessels, for example.

Šmahel’s footnote 19 gives as his sources:

Eine Photographie aus dem St.-Georg-Kloster nebst Transkription und Übersetzung enthält Nováček, V. J.: Amulet ze XIV. století, nalezený v chrámu sv. Jiří na Hradě Pražském [Ein Amulett aus dem XIV. Jahrhundert aus der Basilika des hl.Georg auf der Prager Burg]. ČL 10 (1901) 353 f. Es bleibt zu erwähnen, daß ein Mönch aus dem Kloster Ostrov den Nonnen des St. Georg Klosters zu Beginn des 15. Jahrhunderts das gegenseitige Beschenken mit sog. Amuletten oder Talismanen an bestimmten Tagen im Jahr vorhielt, siehe Truhlář, Josef: Paběrky z rukopisů klementinských VIII. [Nachgelesenes in den Clementinischen Handschriften VIII.]. VČA 7 (1898) 210f. Aufschriften und Buchstaben auf mittelalterlicher Keramik belegt Švehla, Josef: Nádoby a nápisy na středověké keramice z Ústí Sezimova a Kozího hrádku [Aufschriften auf mittelalterlichen keramischen Gefäßen aus Ústí Sezimovo und Kozí hrádek]. ČSPSČ 19 (1911) 10-18. Interpretationen der beschützendmagischen Funktion der Aufschriften auf mittelalterlichen Glocken (lateinisch geschriebene hebräische Ausdrücke, Buchstaben des griechischen Alphabets u.a.) finden sich bei Fiodr, Miroslav: Nápisy na středověkých zvonech [Aufschriften auf Mittelalterlichen Glocken]. SPFFBU C 20 (1973 148f.

…which Google Translate also turned into pretty good English (has GT recently been upgraded, it seems better than usual?)…

Nováček, V. J.: Amulet ze XIV. Století, nalezený v chrámu sv. Jiří na Hradě Pražském [An amulet from the 14th century from the Basilica of St. George in Prague Castle]. ČL 10 (1901) p.353 contains a photograph from the St. Georg monastery along with transcription and translation.

It should be mentioned that at the beginning of the 15th century, a monk from Ostrov Monastery reproached [the nuns for] the mutual gifts of so-called amulets or talismans on certain days of the year, see Truhlář, Josef: Paběrky z rukopisů klementinských VIII. [Manuscript fragments from the Clementinum VIII.]. VČA 7 (1898) p.210.

Inscriptions and letters on medieval ceramics are documented by Švehla, Josef: Nádoby a nápisy na středověké keramice z Ústí Sezimova a Kozího hrádku [Inscriptions on medieval ceramic vessels from Ústí Sezimovo and Kozí hrádek]. ČSPSČ 19 (1911) 10-18.

Interpretations of the protective, magical function of the inscriptions on medieval bells (Latin Hebrew expressions, letters of the Greek alphabet, etc.) can be found in Fiodr, Miroslav: Nápisy na středověkých zvonech [Inscriptions on Medieval Bells]. SPFFBU C 20 (1973 p.148

This in turn leads Google to a footnote on p.65 of Benedek Lang’s (2008) “Unlocked Books” which I mentioned in my 2010 post. Lang gives the following transcription of the charm’s text, which refers to the famous legend/story of Seven Sleepers:

+ In nomine + patris + et filii + et spiritus + sancti + In monte + Celion + requiescunt septem dormientes + Maximianus + Martinianus + Malcus + Constantinus + et Dionisius + Seraphion + et Johannes. Domine Jesu Christe liberare digneris hanc famulam Dobrozlauam a febribus quintanis. pax + nax vax sit huic famule dei remedium Amen.”

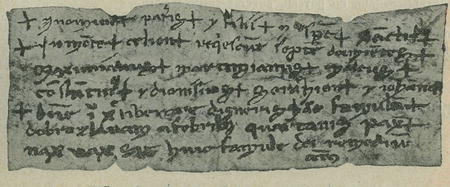

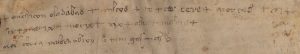

Actually, it turns out that we can do even better than this, because Nováček’s 1901 article has been placed online. Nováček describes the strip of parchment as being 10cm x 4cm, folded three times and then pierced twice, through which holes a narrow strip of the same parchment was threaded. He describes the lettering as somewhat poor, but definitely dating to the first half of the 14th century.

To my pleasant surprise, the scan included a low resolution image of the parchment charm itself:

It’s not the best scan you’ll ever see, sure, but it’s a lot better than nothing. 🙂 To my eye, a reasonable transcription would be:

+ In nomine + patris + et filii + et spirit[us] + sa[n]cti + In mo[n]te + Celion + requiescu[n]t septe[m] dormie[n]tes + Maximia[n]us + Martinianus + Malcus + Co[n]sta[n]tin[us] + et Dionisius + Seraphion + et Joha[n]nes. Dom[ine] J[esu] Ch[rist]e liberare digneris hanc famula[m] + dobrozlauam a febrib[us] quintan[us]. pax + nax vax sit huic famule dei remediu[m] a[m]en.

Dr. Čeněk Zíbrt

Finally, Nováček directs readers who would like to know more to an article by Dr. Čeněk Zíbrt entitled »Kouzla a čáry starých Čechů« in Archaeolo-gických Památkách XIV (1887), which details inscriptions found on a number of similar amulets.

Of course, I couldn’t let the minor impediment of not even remotely reading Czech stop me pursuing this a little further. 😉 So I tracked down a Czech academic website where all the volumes of “Památky archaeologické a místopisné” were digitized, and found the article in Volume XIV (1887-1889).

However, just to make life difficult, Zíbrt’s article was broken up into lots of smaller pieces: but I’ll summarize the relevant pieces below.

Zíbrt starts by confirming that he had seen written mention of such amulets in the Třeboň and Jindřichohradecký archives. For example, in 1474 the Kantor in Soběslav wrote to the Burgrave in Krumlov about a “Mrs. Makhny”. She had been instructed to wear a certain amulet around her neck for nine days, because the Burgrave of Chúsnický had said that when he wore the same thing around his neck, the disease had gone away. (Arch. Třeboň.)

Similarly, the Catholic missionary Matěj Václav Šteyr wrote in 1719 about people believing (falsely) that amulets guard against fevers. The words found on such amulets were:

- Hax, pax, max etc

- Arac, Amou etc.

- Barata, Daries etc

- Galhes Galdis etc

- Gibel, Cor etc

- Ira, Bira, Lira, Pira, etc (to protect against the bite of a rabid dog)

In 1564, the scholar Wierus (who wrote “De praestigiis daemonum”) wrote that he had seen “Hax pax max Deus adimax” written on an amulet to protect against rabies. Rukop. univ. knih. Pr. (17 D 4), str. 81 contains the following: “DEX PEX NOVA MXZATX VAhX PRAX ZVAX ZISX PYX IVONXAX ANIX”. [Might some of these Xs actually be crosses? NP]

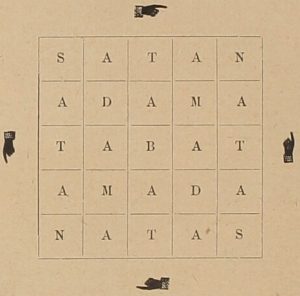

The last amulet Zíbrt discusses is a Czech variant on the SATOR / AREPO / TENET / OPERA / ROTAS magic square:

Along the way, Dr. Zíbrt confesses that the article was triggered by seeing a similar series of amulet-related articles from 1880 onwards in Verhandl d. Berlin. Gesellschaft f. Anthropologie, Ethnologie u. Urgeschichte, and feeling affronted that nothing similar had been written from the point of view of the Czech archives. But I’ll leave those articles for another day, this post is already more than large enough. 🙂

Meanwhile in Vltava…

One Czech web page reports the specific wording of a formula found being used on an amulet in the Vltava region to protect against fever, as reported by Matěj Václav Šteyr:

“Ve jménu Otce i Syna i Ducha svatého Ve vrchu Kelion odpočívá sedm spících….Pane Ježiši Kriste osvoboditi ráčiž tuto služebnici od zimních pětidenních. Pax nax vax budiž této služebnici Božím lékem amen. ” [In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Lord Jesus Christ, free this servant from the quintan fever. Pax nax vax let this servant gain God’s cure. Amen].

According to the dissertation by Mgr. Jitka Rejhonová, Matěj Václav Šteyr was the most published Bohemian missionary of the Baroque period. Anyone wishing to read more Czech is welcome to download this and find out more.

Regardless, it already seems more than clear to me that this specific charm text (combining the Seven Sleepers with pax nax vax to protect the wearer against fever) was a long-held belief in the region, from the 14th or 15th century right through to the 18th century.

Finally, f116v…

So, the question is: what does this tell us about the three-line block of marginalia on the Voynich Manuscript’s final page (f116v)?

I can certainly easily see how the middle line might (before one or more heavy-handed emenders got in on the act) have originally been “six + pax + nax + vax + ahia + ma+ria +”, so my previous suggestion that this block of text might have been the text of a charm still basically stands.

Moreover, given that it seems to have been traditional to write amulet charms on a piece of vellum (presumably because vellum is so durable), I wonder whether the reason someone wrote the charm on this sheet was because they intended to then cut it out and use it as magical protection. Perhaps, having written it, that person then realized that there was writing on the other side, and so decided (or was told) to leave it instead?

Finally, given the long-standing link between the story of the Seven Sleepers and pax nax vax, I now wonder whether the first word originally was not “michiton” but in fact “m[onte] celion“. Something to think about, anyway. 🙂

Other Pax nax vax examples…

In his (2011) “Norse Magical and Herbal Healing“, Ben Waggoner takes a close look at AM 434a 12mo in the Arnamagnæan Institute at the University of Copenhagen, an Old Norse-Icelandic medical text from circa 1500.

In his footnote 158 to the phrase “res [shape], fres †, pres †, tres †, gres †”, Waggoner notes:

The magic words are gibberish. MS Royal Irish Academy 23 D 43 uses similar words in blood-stopping charms: fres † prares † res † pax † vax † nax † (Larsen, Medical Miscellany, p. 138) and fres pres res rereres reprehex (Larsen, Medical Miscellany, p. 139). A blood-stopping charm in AM 461 has pax, vax, vax, hero, boro, iuva tartar gegimata, and another in the same manuscript has sumax pax (Kålund, Alfræði Íslenzk, vol. 3, pp. 109, 111).

MS Royal Irish Academy 23 D 43, which was written a little before 1486, is described in Henning Larsen’s 1926 article in Modern Philology (it’s in JSTOR): Larsen believes that it was assembled at Munkelif in Bergen from primarily Norwegian sources. However, the full discussion seems to be in Larsen’s ultra-rare 1931 book “An Old Icelandic Medical Miscellany” (which I haven’t seen).

Handritið AM 461 12mo is discussed here (admittedly in Icelandic): “Consummatum est, inclinato capite emisit spiritum. Pax, vax, vax, hero, boro, iuva tartar gegimata + In nomine patri et spiritus sancti”. (p.124) This same (encyclopaedic) manuscript includes an Icelandic Cisiojanus, which is nice.

My point is that the fifteenth century craze for using “pax nax vax” seems to have happened all across Europe. Anyone hoping to fix this just to Bohemia will therefore probably be fairly disappointed. Just thought I’d say!

PS: also mentioned in AM 434a is the formula where “a man writes these words in Latin letters with dog’s blood on his own wrist: “Max, píax, ríax”…” (p.48)

Pax Nax Vax’s Father, Rex Pax Nax

For the benefit of anyone trying to Google more stuff about Pax Nax Vax, I should add that it seems highly likely to me that it evolved out of a well-known earlier toothache charm, Rex Pax Nax. For example, there’s the one you can read in Edward Thomas Pettit’s critical edition of the Lacnunga (Remedies) in MS. Harley 585, f.183a, b (11th Century):

[Contra dolorum dentium]:

(Cristus) sup(er) mamoreum sedebat; Petrus tristis ante eum stabat, manum ad maxillum tenebat, et interrogebat eum D(om)in(u)s dicens:

“Quare tritis es, Petre?”

Respondit Petrus et dixit :

“D(omi)ne, dentes mei dolent.”

Et D(omi)n(u)s dixit :

“Adiuro te / migranea uel gutta maligna p(er) Patre(m) et Filium et Sp(iritu)m S(an)c(tu)m et p(er) celum et terram et p(er) XX ordines angelorum et p(er) LX p(ro)phetas et p(er) XII apostolos et p(er) IIIIor euangelistas et p(er) om(ne)s s(an)c(t)os q(u)i D(e)o placuerunt ab origine mundi, ut non possit diabolus nocere ei, nec in dentes, nec in aures, nec in pal[a]to, famulo D(e)i, ill(i) non ossa fra[n]gere, nec carnem manducare, ut non habeatis potestatem nocere ill(i), non dormiendo, nec uigilando, nec tangatis eum usq(ue) LX annos et unum diem. “

Rex pax nax in (Cristo) / Filio . Am(en) . Pater noster.

A later (and significantly cut-down) version of this from the Wolfsthurn handbook appears in the introduction to Kieckhefer’s “Magic in the Middle Ages” (p.4). There, it says that a person afflicted by toothache should have “Rex pax nax in Cristo filio suo” written on his/her jaw. (This came from the 14th century physician John of Gaddesdon, according to the Routledge History of Disease, p.56: BL Harley 2558 is online here).

Rex pax nax also appears in Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ashmole MS 1451, and San Marino, Huntington Library HM 64, and no doubt close to a hundred other medieval manuscripts. Hence my best guess is that pax nax vax started its life as a garbled / misremembered version of Rex pax nax, a formula which was still reasonably current in the 15th century.

[Incidentally, if I had money to burn, I’d now buy access to Lea Olsan’s (2003) “Charms and Prayers in Medieval Medical Theory and Practice” in Social History of Medicine, Volume 16, Issue 3, December 2003, Pages 343–366, as well as a copy of Don C. Skemer’s (2010) “Binding words: Textual amulets in the Middle Ages“. But I’ve already managed to blow half of my 2020 book budget, so I hope to return to these at a later. *sigh* ]