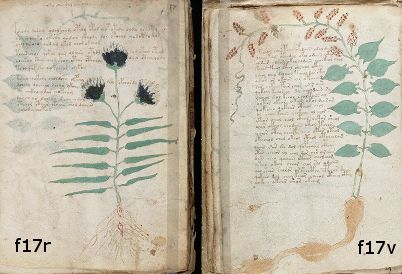

A new day brings a new Google Adwords campaign from Edith Sherwood (Edith, please just email me instead, it’ll get the word out far quicker), though this time not promoting another angle on her Leonardo-made-the-Voynich-Manuscript hypothesis… but rather a transposition cipher Voynichese hypothesis. Specifically, she proposes that the Voynich Manuscript may well be Italian written in a simple (i.e. ‘monoalphabetic’) substitution cipher, but also anagrammed to make it difficult to read.

Anagram ciphers have a long (though usually fairly marginal) history: Roger Bacon is widely believed to have used one to hide the recipe for gunpowder (here’s a 2002 post I made on it), though it’s not quite as clear an example as is sometimes claimed. And if you scale that up by a factor of 100, you get the arbitrary horrors of William Romaine Newbold’s anagrammed Voynich ‘decipherment’ *shudder*.

More recently, Philip Neal has wondered whether there might be some kind of letter-sorting anagram cipher at play in the VMs: but acknowledges that this suggestion does suffer from various practical problems. I also pointed out in my book that Leonardo da Vinci and Antonio Averlino (‘Filarete’) both used syllable transposition ciphers, and that in 1467 Alberti mentioned other (now lost) kinds of transposition ciphers: a recent post here discussed the history of transposition ciphers in a little more detail.

So: let’s now look at what Edith Sherwood proposes (which is, at least, a type of cryptography consistent with the VMs’ mid-Quattrocento art history dating, unlike many of the more exotic ciphering systems that have been put forward in the past), and see how far we get…

Though her starting point was the EVA letter assignments (with a few Currier glyphs thrown in), she then finessed the letter-choices slightly to fit in with the pharma plant label examples she picked: and there you have it (apart from H, J, K, Q, X, Y, Z and possibly F, which are all missing). All you’d have to do, then, is to anagram the rest of the text for yourself, sell the book rights, and retire to a sea-breezy Caribbean island.

![]()

Might Edith Sherwood be onto something with all this? No, not a hope: for example, the letter instance distribution is just plain wrong for Italian, never mind the eight or so missing letters. As with Brumbaugh’s wobbly label-driven decipherment attempts, I somehow doubt you would ever find two plausible adjacent words in the main body of the text. Also: what would a sensible Italian anagram of “qoteedy” (“volteebg”) be?

Her plants are also a little wobbly: soy beans, for example, were only introduced into Europe in the eighteenth century… “galioss” is a bit of a loose fit for galiopsi (not “galiospi”, according to “The Botanical Garden of Padua” on my bookshelf), etc.

As an aside, I rather doubt that she has managed to crack the top line of f116v: “povere leter rimon mist(e) ispero”, “Plain letter reassemble mixed inspire” (in rather crinkly Italian).

All the same, it is a positive step forward, insofar as it indicates that people are now starting to think in terms of Quattrocento dating and the likely presence of non-substitution-cipher mechanisms, both of which are key first steps without which you’ll very probably get nowhere.