I’ve just watched a sort-of-mostly-interesting voynich.ninja interview with Adam Lewis, whose senior thesis at Puget Sound I mentioned here a few days ago.

However, one particular part of his argument (as presented in the interview, at least) made no real sense to me at all: that even though the Voynich offers (Lewis says) a decent-sized corpus of text to work with [in fact, it’s possibly the largest ciphertext from the pre-machine-cipher era], its text style is somehow too ‘samey’ for linguists to find the weak link in (and hence crack).

In fact, we have (at least) two ‘languages’ to work with, better known in Voynich circles as Currier A and Currier B (named after the distinguished US code-breaker Captain Prescott Currier, who first noted them in the 1970s), though it remains an open question as to whether or not they are closer to ‘dialects’ than distinct ‘languages’ per se. Hence I’m not entirely convinced by Lewis’s argument.

Regardless, might there be some subtle thread (whether linguistic, cryptological, or whatever) connecting two different blocks of text that we can trace between the two pages they appear on? Might we be able to find a tentative internal Voynichese text match (be it ever so small) to cast some faint light on both parts, in precisely the way that Adam Lewis asserts that we cannot?

Well… I hope you’ll agree that it’s worth attempting, so let’s give it a go, eh? 🙂

Three Pages, One Plant?

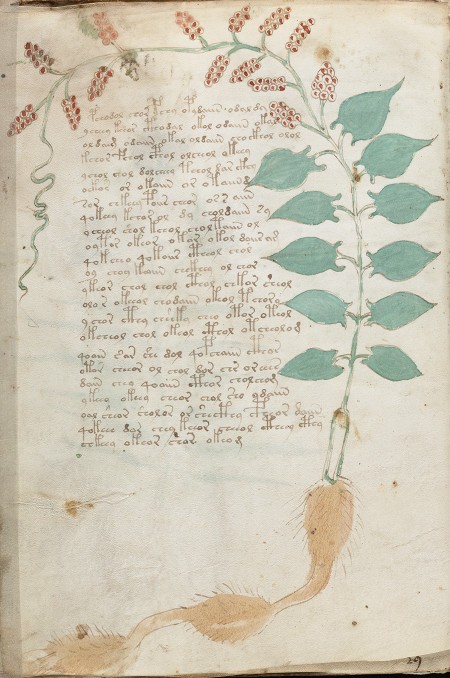

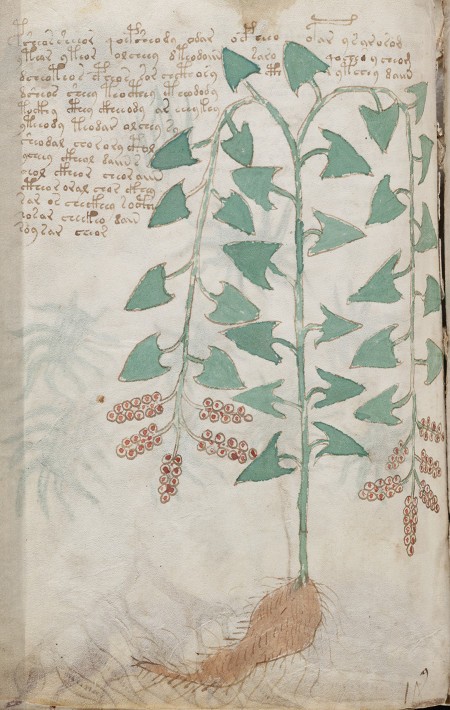

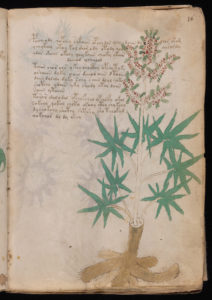

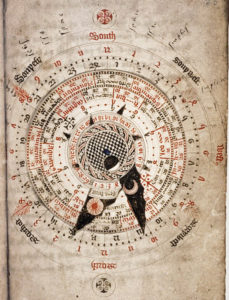

I believe that most Voynich researchers would agree that – very unusually – a single plant seems to appear in three separate places in the manuscript: f17v, f96v, and f99r. Long-suffering Cipher Mysteries readers may also remember that I posted about these pages back in 2013.

Note that identifications of the plant are somewhat nebulous and unsure:

* Dana Scott – wild buckwheat (Ellie Velinska tends to agree with this, or perhaps bryony)

* “biologist from Finland” – – Rumex acetosella? or Smilax aspera (=common smilax) or Smilax excelsa. Or Dioscorea communis / Tamus communis?

* Peter – Tamus communis or Smilax aspera

* MarcoP – Cadamosto’s “vitis nigra” (black vine) commonly “tamo” (“vitis nigra tamo dice lo vulgo”), i.e. Tamus communis

* JKP – suggests many different plant matches

* Kieran Coughlan – Creeping Nightshade (Solanum Dulcamara)

* Edith Sherwood – yam (even though yam is post-Columbus) – and she thinks she can see Leonardo da Vinci’s signature hidden in its hairy roots. As always, make of that what you will.

(Doubtless there are many more to be found, but that’s the point where I lost interest.)

Codicologically: even though f96v and f99r would at first appear to have had a pair of pages inserted between them at some stage (i.e. f97 and f98), they ended up facing each other in the Voynich’s final state. Moreover, f96v is the last page of quire 17, and f99r is the first page of quire 19: my best reading (that I put forward in 2012 in Frascati) is that there was never any such pair of inserted pages, but that instead someone else had previously misnumbered the final two quires (Quire 19 and Quire 20), and that the two extra pages there were added to account for the ‘Quire 18’ that was never actually there. Perhaps none of this is actually important: but I think there’s a good chance that – contrary to their final folio numbering – f96v and f99r have sat facing each other for some time, perhaps even in the original gathering order.

Anyway, comparing the blocks of text reveals something I think is rather unusual, and which may possibly come as a surprise to many who look more at the drawings than at the text: that even though they share the same plant drawing, they really are – when you look a little closer – very different indeed from each other.

f17v

1. pchodol.chor.fchy.opydaiin.odaldy

2. ycheey.keeor.cthodal.okol.odaiin.okal

3. oldaim.odaiin.okal.oldaiin.chockhol.olol

4. kchor.fchol.cphol.olcheol.okeeey

5. ychol.chol.dolcheey.tchol.dar.ckhy

6. ockhor.or.okaiin.or.otaiind

7. sor.chkeey.paiir.cheor.os.s.aiin

8. qokeey.kchar.ol.dy.choldaiin.sy

9. lcheol.shol.kchol.choltaiin.ol

10. oytor.okeor.okar.okol.daiir.am

11. qokchey.qokaiir.ctheol.chol

12. oy.choy.kaiin.chckhey.ol.chor

13. ykeor.chol.chol.cthol.chkor.sheol

14. olor.okeeol.chodaiin.okeol.tchory

15. ychor.cthy.chshky.cheo.otor.oteol

16. okcheol.chol.okeol.cthol.otcheolom

17. qoain.shar.she.dol.qopchaiin.cthor

18. otor.cheeor.ol.chol.dor.chr.oreees

19. dain.chey.qoaiin.cthor.cholchom

20. ykeey.okeey.cheor.chol.sho.odaiin

21. oal.sheor.sholor.orshecthy.cpheor.daiin

22. qokeee.dar.chey.keeor.cheeol.ctheey.cthy

23. chkeey.okeor.shar.okeom

A list of mildly distinctive features of f17v might well include:

* the “ol.olol” repetition on line 3

* the single-leg gallows on line 1 (possibly a Neal Key?) and on line 4. (Might line 4 in fact be the start of a second paragraph?)

* note that the single-leg gallows on line 17 also looks like it might be the top line of a paragraph

* the “qoain” on line 17 (this appears only 7 times in the manuscript) and “qoaiin” on line 19 (this appears only 23 times)

* the “autocopied”-like choldaiin/choltaiin pair on lines 8 and 9

* chol appears 11 times (as itself and within other words)

* chol.chol (line 13) appears 39 times in A pages but only a single time in B pages

f96v

1. psheossheeor.qoepsheody.odar.ocpheeo.opar.ysarorom

2. yteor.yteor.olcheey.dteodaiin.sary.qoches.ycheom

3. dcheoteos.cpheos.sor.chcthory.cth.ytchey.daiin

4. dsheor.sheey.teocthy.ctheodody

5. tockhy.cthey.ckheeody.ar.cheykey

6. yteeody.teodar.olchey.sy

7. sheodal.chorory.cthol

8. ycheey.ckheal.daiin.s

9. oeol.ckheor.cheor.aiin

10. ctheor.oral.chor.ckhey

11. sar.os.checkhey.socthh

12. sosar.cheekeo.dain

13. soy.sar.cheor

Here:

* the four single-leg gallows (p) on line 1 could very easily be flagging Neal Keys in some way (e.g. [p] + “sheossheeor.qoe” + [p])

* there are only three instances of “yteor” in the whole manuscript, and line 2 has two side by side

* the way that “s” is used as the first character of lines 11-13 gives the appearance of being filler in some way (e.g. a null)

* there’s also an autocopyist-style diagonal set of “sar”s on lines 11-13 (sar / sosar / soy.sar) that also looks like filler

* the repetition of ctheodody and ckheeody on lines 4 and 5 makes it look as though ctheodody may have been a miscopying of ctheody

Hence even though the use of ‘language’ superficially appears similar to f17v (Currier-wise), there are very few actual similarities.

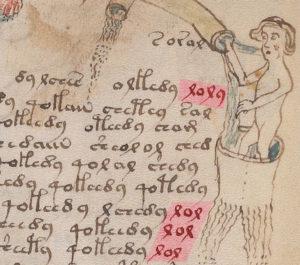

f99r, final paragraph

1. tolkeey.ctheey

2. ykeol.okeol.ockhey.chol.cheodal.okeor.olcheem.orar

3. okeeey.keey.keeor.okeey.daiin.okeols.aiin.olaiir.oolsal

4. qokeey.okeey.qokeey.okesy.qokeey.sar.sheseky.or.al

5. yshain.yckhey.octhey.dy.daiin.okor.okeey.shcthy.sh

6. ychor.ols.or.am.airam

Here, “qokeey.okeey.qokeey.okesy.qokeey” on line 4 is exactly the sort of repetitive garbage that reduces attempted linguistic decryptions to mush while simultaneously giving heart to hoax theorists and their CompSci tables.

A vs B, again

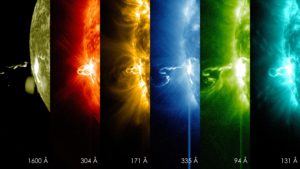

We can try categorize these three pages by revisiting Currier’s original notes on A and B,:

(a) Final ‘dy’ is very high in Language ‘B’; almost non-existent in Language ‘A.’

(b) The symbol groups ‘chol’ and ‘chor’ are very high in ‘A’ and often occur repeated; low in ‘B’.

(c) The symbol groups ‘chain’ and ‘chaiin’ rarely occur in ‘B’; medium frequency in ‘A.’

(d) Initial ‘chot’ high in ‘A’; rare in ‘B.’

(e) Initial ‘cth’ very high in ‘A’; very low in ‘B.’

(f) ‘Unattached’ finals scattered throughout Language ‘B’ texts in considerable profusion; generally much less noticeable in Language ‘A.’

Additional observations noted by Rene Zandbergen:

(g) The very frequent character combination ed is almost entirely non-existent in all A-language pages.

(h) The very common character combination qo is almost completely absent in the zodiac pages and the rosettes page, but appears everywhere else.

(i) The common character combination cho does not appear in the biological pages (and the rosettes page), but it does in other B-language pages.

From this, we can say (somewhat uncomfortably) that:

* f17v is a definitely-Currier-A page (it has lots of “chol” and “chor” instances, as well as cth- words)

* f96v is a sort-of-a-Currier-A page

* f99r is a sort-of-a-Currier-B page

And so we get to the awkward situation I highlighted back in 2013, that A vs B is far too simplistic to be a globally useful razor, and that we also don’t yet have a good ‘roadmap’ for how the ‘language’ used in the Voynich Manuscript evolves and changes through its pages. Which is essentially why I think that Adam Lewis is being too reductive when he claims that Voynichese is too samey across its pages to be crackable – the actual situation would seem to be that Voynichese is actually too unsamey for anyone to get a grip on.

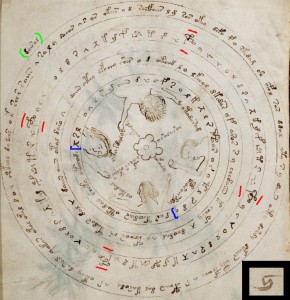

But is there a match?

Back in 2013, commenter Šuruppag suggested on my original page that there might possibly be a very short match between all three blocks of text. Specifically (as transcribed above):

* f17v line 5: ychol.chol.dolcheey

* f96v line 2: yteor.yteor.olcheey

* f99r line 3: keey.keeor.okeey

Šuruppag continued:

A nice little sequence that occurs once in each passage. Seems to show similar pattern and characters.

Perhaps this sequence (possibly the name of the plant?) shows us the evolution of the cipher. Feel free to criticize if you don’t think so.

I would add that there’s reasonably good evidence (I flagged this in The Curse of the Voynich in 2006) that “-y” may mark where a longer word has been truncated: and so “keey” on f99r could very easily be a (slightly) truncated version of “keeor”. In which case we might wonder whether “yt” on f96v is enciphering the same underlying letter as “k” on f99r.

Again, in Curse in 2006 I proposed that EVA ok / ot / yk / yt (all of which appear prominently in label-driven sections such as the zodiac pages, e.g. “otolal”) might well be verbose cipher pairs, whereas EVA t / k (i.e. where not immediately preceded by o or y) might well be some kind of transposition cipher where a different letter gets inserted from elsewhere in the text (t and k are basically interchangeable in almost all circumstances). This makes me suspect here that the last word of the phrase on f99r should actually be olkeey rather than okeey, because “ok” would then be a verbose cipher whereas “olk” would be parsed as “ol-k”.

I also wrote in Curse that I thought not only that EVA e / ee / eee / ch shapes were verbosely enciphered vowels, but that their mapping and use seemd to change between A and B pages. So I for one would not be hugely disturbed if it were to be the case that EVA “e-or” in f96v reappears as EVA “ee-or” in f99r.

And finally, I have also proposed that where Voynichese words start with “d-“, this may well turn out to be a signal that a longer word has been split up into two shorter words. (For example, I suspect that daiin daiin sequences encipher groups of Arabic digits that should be joined together.)

Putting all these fragments together, I wonder if perhaps the three lines (if the various miscopyings were corrected, and the f99r -y rectified as -or, and the words reassembled) were originally supposed to be parsed as:

* f17v line 5: ychol..chololcheey – – – or perhaps “ychol.ychololcheey”

* f96v line 2: yteor.yteorolcheey

* f99r line 3: keeor.keeorolkeey

Hence it seems to me that what might well be going on in the f99r line is that three “k”s are being used to stand in for yt / yt / ch respectively, i.e. that the encipherer is using a transposition (i.e. replacement from elsewhere in the text) cipher trick rather than f96v’s verbose cipher trick to encipher the same plaintext word.

But what then of f17v’s text? My best current guess is that this version may well be closer still to the same small block of plaintext being enciphered on all three pages.

One cipher alphabet, multiple verbose ciphers?

More awkwardly than all of the above, the above seems to suggest that chol in the first page be the same as eor in the second page and eeor in the third page: that is, that even though the Voynichese letters are the same across different pages, the arrangement of verbose ciphers using those covertext letters may well be changing. Is our inability to read Voynichese then largely a consequence of multiple verbose cipher arrangements having been used?

When this kind of Voynichese discussion comes up, I often think back to my late (and intensely argumentative) friend Glen Claston. When he was building up his Voynichese transcription, he often noticed (as he mentioned to me a couple of times) that the patterns and styles of words would “shift” every few lines or paragraphs, as though it internally changed into a different gear or mode. He was never able to quantify this shift more precisely (even though he was a keener observer than almost everyone), but perhaps there lurks at the heart of Voynichese some kind of verbose cipher modality – not enough to disrupt the overall “look” (i.e. of the covertext), but more than enough to throw the decryptor hounds off the crypto-scent.

That is, perhaps what these three lines is trying to tell us is that we should be looking not for a single global verbose cipher key (as might be suggested by the way that the covertext consistently uses a relatively small set of cipher glyphs), but for a number of different (and rather more localized) verbose cipher keys. Voynichese’s covertext may be formed from a single set of glyphs across all its pages, but might the complexity around the different blur of Currier ‘languages’ actually be telling us that there are multiple encryption schemes in use?

If that is correct (to even some degree), what would we need to do to get under Voynichese’s skin? I’ve often spoken of the need to try to map Currier A usage to Currier B usage (to try to identify equivalent sequences in the two parts), but perhaps this is only 5% of the larger challenge, and moroever a step that makes no sense until the verbose ciphers have been even partially mapped – for it could very well be that a part of a single page might well need to be remapped to a different part of the same page in order to be able to parse it, let alone read it. Perhaps the first step should be to try to find examples of Voynich Manuscript pages that exhibit Clastonian multimodality (i.e. where there is an apparent shift in the system within the page), and see if we can quantify how the changes in behaviour work in practice, just so that we can even try to parse what is going on.

Tricky, though. 🙁