Statistical and cryptanalytical analyses tend to assume that ciphers will fit one of a small number of well-known and well-researched pigeonholes (e.g. Vigenère, autokey, etc). Unfortunately, this kind of “backwards attack” can often be stopped dead if the encipherer includes one or more additional steps sideways, unless the backwards attacker happens to be cunning or lucky enough to reconstruct those tiny steps.

But as they knew in Bletchley Park, it is sometimes possible to “forwards attack” cryptograms. There, a “crib” was the name BP codebreakers used to describe where you already had the plaintext, typically obtained by decrypting the same message enciphered using a different cipher system: having this would help the code-breakers reconstruct daily settings for the second cipher etc. Just so you know, this is precisely why you should never forward a received (and deciphered) message word-for-word using a different cipher, a lesson many WW2 code bureaux stubbornly failed to learn.

Similarly, the idea behind my “block paradigm” methodology is that if we can use secondary historical clues to determine the plaintext from which a given section of ciphertext was derived, we stand a reasonably good chance (I think) of reconstructing the cipher forwards from there. You can therefore think of it as a high-level “historical crib”, where the plaintext is reconstructed via in-depth research rather than by breaking a parallel cipher.

At the very least, this whole process could very possibly yield a completely different class of problem to solve, which in the case of the Voynich Manuscript shouldn’t be a bad thing, given that a century’s worth of backwards attacks has been largely unproductive. 🙁

But what might the plaintext for the Voynich zodiac look like? Would we even recognize it if we had it in front of us?

The Voynich zodiac section

In the same way that many people have long suspected that the Voynich Manuscript’s “Herbal” section(s) probably contains plant and/or remedy descriptions (albeit secret, valuable or unexpected ones), there has long been a strong – yet untested – historical hypothesis about what the Voynich zodiac section might well contain, which is simply this: per-degree astrology. This is because each sign seems to be divided into 30 elements (29 in the case of Pisces, though this may possibly have simply been a slip of the quill), and there are 30 degrees in each zodiac sign (i.e. 12 x 30 = 360).

The modern history of per-degree astrology is something I covered here before: it moved back from Marc Edmund Jones (1925) to the nineteenth century astrologers “Charubel” (who claimed he channelled his per-degree symbols) and “Sephariel” (who claimed that he copied his from “La Volasfera”, supposedly a Renaissance book by Antonio Borelli / Bonelli [did he mean Guido Bonatti?], but this has never turned up).

It’s often written that Western medieval per-degree astrology arrived from Arabic sources via Pietro d’Abano (while he was in Spain during the 13th century). Heidelberg has a 15th century German translation of his work in MS Cod. Pal. Germ. 832 (“Regensburg, nach 1491”), which Rene Zandbergen mentioned in a comment here back in 2009. (If you look at fol. 36r onwards, you can see a few lines of text for each of the thirty degrees in each of the signs in turn, along with some rather jaunty miniatures.)

Prior to the Arabs, you can doubtless trace all this back to the original Indian sources (Diane O’Donovan pointed to the encyclopaedia-sized “Brihat-Samhita” by Varahamihira), but taking things back that far falls way beyond my paygrade, so I’m not going to attempt it in this post. 🙂

However, if you take the time to read Chapter XII of volume III of Lynn Thorndike’s “History of Magic and Experimental Science”, you’ll see that another medieval writer famously wrote on per-degree judicial astrology: and this is where my search began.

Andalò di Negro

Andalò di Negro (fl. first half of the 14th century) was a noble from Genoa. Boccaccio, who he famously taught “in the movements of the stars”, noted that “since [Andalò] had traversed nearly the whole world, and had profited by experience under every clime and every horizon, he knew as an eye-witness what we learn from hearsay” (De genealogia deorum, XV, 6, quoted in Thorndike, p.195).

One of Andalò’s works (“introductorium ad iudicia astrologie”) that discussed per-degree judidicial astrology was of particular interest to me. So, back in 2009, I managed to get some working photocopies of it courtesy of the Warburg Institute’s Photographic Collection: these were of the two known documents listed further below.

Interestingly (and unlike the Pietro d’Abano-derived Heidelberg manuscript), the key feature that seems to oddly parallel what we see in the Voynich Manuscript’s zodiac section is that these two documents contain only a small amount of data per degree (though admittedly arranged in columns of a table rather than in the form of nymphs, stars and labels).

The first document is at the British Library: I managed to get a look at this in person, kindly thanks (if I recall correctly) to a letter of introduction from Dr David Juste, who was then a historian of astrology at the Warburg Institute. One unusual feature was that a few key parts of the tables were highlighted in different colours, something that wasn’t at all apparent from the black-and-white photographs taken for the Warburg in the (I guess) 1920s or 1930s. (Sadly, the colour notes I took at the time have long since disappeared).

* BL Add. MS 23770 (BL: “14th century”, Warburg: “circa 1350”)

http://searcharchives.bl.uk/IAMS_VU2:IAMS032-002097417 – “Letter of introduction required to view this manuscript”

1. “INTRODUCTORIUS ad iudicia astrologie co[m]positus ab A[n]dalo de Nigro de Janua;” with paintings of the signs of the Zodiac, the planetary Gods, etc., ff. 1-44.

Aries (8r), Taurus (9v), Gemini (11r), Cancer (12v)

Leo (13v), Virgo (15r), Libra (16v), Scorpio (17v)

Sagittarius (18v), Capricorn (19v), Aquarius (20v), Pisces (21v)

You can see monochrome thumbnails of these twelve images on the Warburg Institute’s Photographic Collection.

In the case of the second document, since 2009 Cod. Fonds 7272 has been placed online and made downloadable by BNF. As a result, I can include links directly into the Gallica pages for you (which is nice).

* BNF Cod. Fonds Latin 7272

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8452771j

Aries (112r), Taurus (114r), Gemini (115v), Cancer (116v)

Leo (118v), Virgo (119v), Libra (121r), Scorpio (122v)

Sagittarius (124v), Capricorn (126r), Aquarius (127v), Pisces (129r)

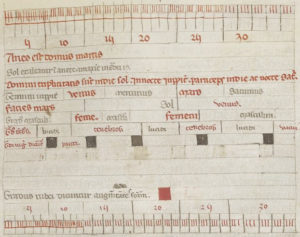

Here is the Aries table as it appears in BNF Cod. Fonds Latin 7272, courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France via Gallica:

By way of a guide, fol. 22v of BL Add. MS 23770 explains (says Thorndike, p.192 n.5) Andalò di Negro’s “fivefold distinction of degrees within the signs: 1, masculine or feminine; 2, lucidus, tenebrosus, fumosi, or vacui; 3. putei; 4. azamena (like the putei, to be avoided); 5, augmentates fortunam.”

However, I have to mention at this point that according to Boncompagni’s (1875) “Un Catalogo dei Lavori di Andalò di Negro” (an offprint taken from “Bullettino di Bibliographia e di Storia delle Scienze, Matematiche E Fisiche”, Tomo VII – Luglio 1874, and for an original of which I paid a load of money several years ago but which is now available print-on-demand from Kessinger *sigh*), there might possibly be a third copy still floating around.

Boncompagni (pp.54-55) mentions that an 1834 alphabetical index of the Biblioteca Altieri di Roma published by Federico Blume lists: “de Nigro, Andali de Ianua, Introductorium ad iudicia astrologiae, Fogl. membr. V.E.5”. Moreover, Emilio Altieri’s index to the Biblioteca Altieri (car. 11a, recto, lin.2) reads: “Andalus de Nigro de Janua, de Astrologia, Pil. 13, Lett. A. Numo. 5”. Yet according to a 1690 index, “Il detto Altieri non possiede ora alcun esemplare manoscritto d’alcun lavoro di Andalo di Negro“, so it seems that it had already disappeared by then.

That sums up the known versions of this work tolerably well: but what might these tell us about the Voynich zodiac? Obviously, that’s a good question something I’ll have to leave for a follow-on post…