At the start of my own VMs research path, I thought it was important to consider everyone’s observations and interpretations (however, errrm, ‘fruity’) as each one may just possibly contain that single mythical seed of truth which could be nurtured and grown into a substantial tree of knowledge. Sadly, however, it has become progressively clearer to me as time has passed that any resemblance between most Voynich researchers’ interpretations (i.e. not you, dear reader) and what the VMs actually contains is likely to be purely coincidental.

Why is this so? It’s not because Voynich researchers are any less perceptive or any more credulous than ‘mainstream’ historians (who are indeed just as able to make fools of themselves when the evidence gets murky, as Voynich evidence most certainly is). Rather, I think it is because there are some ghosts in our path – illusory notions that mislead and hinder us as we try to move forward.

So: in a brave (but probably futile) bid to exorcise these haunted souls, here is my field guide to what I consider the four main ghosts who gently steer people off the (already difficult) road into the vast tracts of quagmire just beside it…

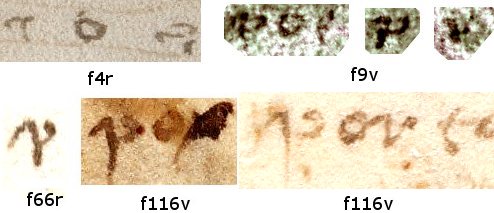

Ghost #1: “the marginalia must be enciphered, and so it is a waste of time to try to read them”

I’ve heard this from plenty of people, and recently even from a top-tier palaeographer (though it wasn’t David Ganz, if you’re asking). I’d fully agree that…

- The Voynich Manuscript’s marginalia are in a mess

- To be precise, they are in a near-unreadable state

- They appear to be composed of fragments of different languages

- There’s not a lot of them to work with, yet…

- There is a high chance that these were written by the author or by someone remarkably close to the author’s project

As with most non-trick coins, there are two quite different sides you can spin all this: either as (a) good reasons to run away at high speed, or as (b) heralds calling us to great adventure. But all the same, running away should be for properly rational reasons: whereas simply dismissing the marginalia as fragments of an eternally-unreadable ciphertext seems to be simply an alibi for not rising to their challenge – there seems (the smattering of Voynichese embedded in them aside) no good reason to think that this is written in cipher.

Furthermore, the awkward question here is that given that the VMs’ author was able to construct such a sophisticated cipher alphabet and sustain it over several hundred pages in clearly readable text, why add a quite different (but hugely obscure) one on the back page in such unreadable text?

(My preferred explanation is that later owners emended the marginalia to try to salvage its (already noticeably faded) text: but for all their good intentions, they left it in a worse mess than the one they inherited. And this is a hypothesis that can be tested directly with multispectral and/or Raman scanning.)

Ghost #2: “the current page order was the original page order, or at least was the direct intention of the original author”

As evidence for this, you could point out that the quire numbers and folio numbers are basically in order, and that pretty much all the obvious paint transfers between pages occurred in the present binding order (i.e. the gathering and nesting order): so why should the bifolio order be wrong?

Actually, there are several good reasons: for one, Q13 (“Quire 13”) has a drawing that was originally rendered across the central fold of a bifolio as an inside bifolio. Also, a few long downstrokes on some early Herbal quires reappear in the wrong quire completely. And the (presumably later) rebinding of Q9 has made the quire numbering subtly inconsistent with the folio numbering. Also, the way that Herbal A and Herbal B pages are mixed up, and the way that the handwriting on adjacent pages often changes styles dramatically would seem to indicate some kind of scrambling has taken place right through the herbal quires. Finally, it seems highly likely that the original second innermost bifolio on Q13 was Q13’s current outer bifolio (but inside out!), which would imply that at least some bifolio scrambling took place even before the quire numbers were added.

Yet some smart people (most notably Glen Claston) continue to argue that this ghost is a reality: and why would GC be wrong about this when he is so meticulous about other things? I suspect that the silent partner to his argument here is Leonell Strong’s claimed decipherment: and that some aspect of that decipherment requires that the page order we now see can only be the original. It, of course, would be wonderful if this were true: but given that I remain unconvinced that Strong’s “(0)135797531474” offset key is correct (or even historically plausible for the mid-15th century, particularly when combined with a putative set of orthographic rules that the encipherer is deemed to be trying to follow), I have yet to accept this as de facto codicological evidence.

To be fair, GC now asserts that the original author consciously reordered the pages according to some unknown guiding principle, deliberately reversing bifolios, swapping them round and inserting extra bifolios so that their content would follow some organizational plan we currently have no real idea about. Though this is a pretty sophisticated attempt at a save, I’m just not convinced: I’m pretty sure (for example) that Q9 and the pharma quires were rebound for handling convenience – in Q9’s case, this involved rebinding it along a different fold to make it less lopsided, while in the pharma quires’ case, I suspect that all the wide bifolios from the herbal section were simply stitched together for convenience.

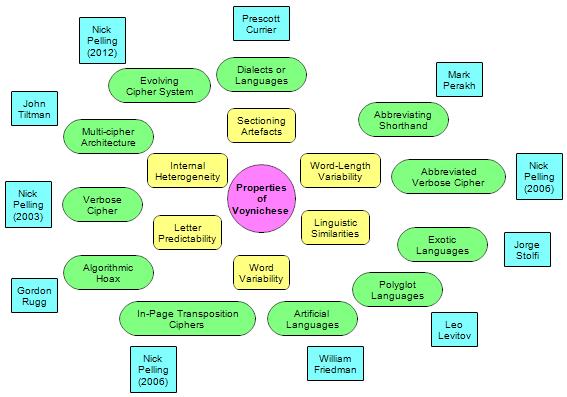

Ghost #3: “Voynichese is a single language that remained static during the writing process”

If you stand at the foot of a cliff and de-focus your gaze to take in the whole vertical face in one go, you’d never be able to climb it: you’d be overawed by the entire vast assembly. No: the way to make such an ascent is to strategize an overall approach and tackle it one hand- and foot-hold at a time. Similarly, I think many Voynich researchers seem to stand agog at the vastness of the overall ciphertext challenge they face: whereas in fact, with the right set of ideas (and a good methodology) it should really be possible to crack it one page (or one paragraph, line, word, or perhaps even letter) at a time.

Yet the problem is that many researchers rely on aggregating statistics calculated over the entire manuscript, when common sense shows that different parts have very different profiles – not just Currier A and Currier B, but also labels, radial lines, circular fragments, etc. I also think it extraordinarily likely that a number of “space insertion ciphers” have been used in various places to break up long words and repeating patterns (both of which are key cryptographic tells). Therefore, I would caution all Voynich researchers relying on statistical evidence for their observations that they should be extremely careful about selecting pragmatic subsets of the VMs when trying to draw conclusions.

Happily, some people (most notably Marke Fincher and Rene Zandbergen) have come round to the idea that the Voynichese system evolved over the course of the writing process – but even they don’t yet seem comfortable with taking this idea right to its limit. Which is this: that if we properly understood the dynamics by which the Voynichese system evolved, we would be able to re-sequence the pages into their original order of construction (which should be hugely revealing in its own right), and then start to reach towards an understanding of the reasons for that evolution – specfically, what type of cipher “tells” the author was trying to avoid presenting.

For example: “early” pages neither have word-initial “l-” nor do we see the word “qol” appear, yet this is very common later. If we compare the Markov states for early and late pages, could we identify what early-page structure that late-page “l-” is standing in for? If we can do this, then I think we would get a very different perspective on the stats – and on the nature of the ‘language’ itself. And similarly for other tokens such as “cXh” (strikethrough gallows), etc.

Ghost #4: “the text and paints we see have remained essentially unchanged over time”

It is easy to just take the entire artefact as a fait accompli – something presented to our modern eyes as a perfect expression of an unknown intention (this is usually supported by arguments about the apparently low number of corrections). If you do, the trap you can then fall headlong in is to try to rationalize every feature as deliberate. But is that necessarily so?

Jorge Stolfi has pointed out a number of places where it looks as though corrections and emendations have been made, both to the text and to the drawings, with perhaps the most notorious “layerer” of all being his putative “heavy painter” – someone who appears to have come in at a late stage (say, late 16th century) to beautify the mostly-unadorned drawings with a fairly slapdash paint job.

Many pages also make me wonder about the assumption of perfection, and possibly none more so than f55r. This is the herbal page with the red lead lines still in the flowers which I gently parodied here: it is also (unusually) has two EVA ‘x’ characters on line 8. There’s also an unusual word-terminal “-ai” on line 10 (qokar or arai o ar odaiiin) [one of only three in the VMs?], a standalone “dl” word on line 12 [sure, dl appears 70+ times, but it still looks odd to me], and a good number of ambiguous o/a characters. To my eye, there’s something unfinished and imperfectly corrected about both the text and the pictures here that I can’t shake off, as if the author had fallen ill while composing it, and tidied it up in a state of distress or discomfort: it just doesn’t feel as slick as most pages.

I have also had a stab at assessing likely error rates in the VMs (though I can’t now find the post, must have noted it down wrong) and concluded that the VMs is, just as Tony Gaffney points out with printed ciphers, probably riddled with copying errors.

No: unlike Paul McCartney’s portable Buddha statue, the Voynich Manuscript’s inscrutability neither implies inner perfection nor gives us a glimmer of peace. Rather, it shouts “Mu!” and forces us to microscopically focus on its imperfections so that we can move past its numerous paradoxes – all of which arguably makes the VMs the biggest koan ever constructed. Just so you know! 🙂