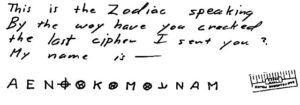

Given that the Zodiac Killer’s first big cipher (the Z408) got cracked so quickly, it shouldn’t really be a surprise that he used a slightly different system for his second big cipher (the Z340). What is (arguably) surprising is that whatever change he made to it has not been figured out since then.

But what was he thinking? What did he want from a cipher? And how might his needs have changed between Z408 and Z340?

The Z408

Ciphers are normally made to be as strong as practically possible, given the technological, time, and resource constraints that apply to both sender and receiver: and with the two main driving needs being privacy and secrecy. Note that these aren’t always the same thing: the way I usually describe it is that while sex with your husband is private, sex with your tennis coach is secret. 😉

And so the first thing I find cryptographically interesting about the Zodiac Killer is that he was creating a cipher from a slightly angle from either of these: and he certainly wasn’t trying to communicate in any normal sense of the word.

Rather, I think that the point of Z408 was to be taunting, and to demonstrate to the police that he was in control, not them.

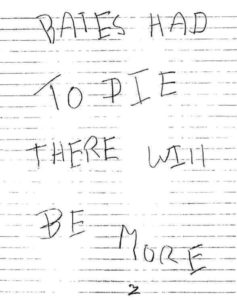

So imagine the Zodiac’s probable fury, then, when little more than a week after his three Z408 cryptograms appeared in local newspapers (the Vallejo Times-Chronicle, the San Francisco Examiner and the San Francisco Chronicle), Donald and Bettye Harden were all over the front pages explaining how they had cracked them.

Didn’t they know who was supposed to be in control here?

What was worse, the Hardens hadn’t used cryptological hardware or even high-powered cryptological smarts. They’d just used the Zodiac’s egoism (they guessed the first letter was “I”) and his psychopathic bragging (they guessed he would use the word KILL multiple times) as keys to his cryptographic front door: and then marched straight in.

I think it’s fairly safe to expect that the Zodiac was pretty pissed off by this.

Note that the Hardens carried on trying to crack the Z340 for many years afterwards: according to their daughter, her “mother wrote poetry and was as absorbed in her writing as she became with the Zodiac codes. She worked on the second code on and off for the rest of her life.”

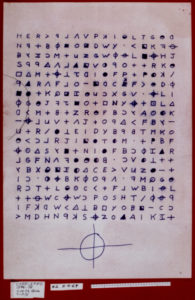

The Z340

Comparing the overall style of the Z340 with that of the Z408, there seems to be plenty of reasons to think that the two are, at heart, not wildly different from each other. And yet (as is widely known) all the big-brained homophonic solvers written since haven’t made any impact on the Z340 at all.

All the same, I think the second interesting thing to note is that the changes to the Z340 system were surely not made to defend against computer-assisted codebreaking (because that hadn’t yet happened), but rather to make the updated system Harden-hardened, so to speak.

What does this mean? Well, we can probably infer that the first letter of the Z340 is almost certainly not I (not that that helps us a great deal) and the Zodiac Killer must have done something to conceal or remove the KILL weakness.

But, in my opinion, that latter change would surely not have been a theoretically-motivated cryptographic adaptation (he was without much doubt an amateur cryptographer), but rather something pragmatic and empirical, perhaps along the lines of:

* adding a repeat-the-last-letter token

* add an LL token

* add an ILL token

* add nulls inside tell-tale words

* etc

But there’s a problem with all of these. In fact, there are several problems. 🙁

The Problems

The first problem is that I don’t currently believe any of the above changes are disruptive enough to explain what we see in the Z340.

The basic stats of the four main Zxxx ciphers are:

Z408: 408 symbols, from a set of 54 unique symbols. (Note: E has 7 homophones, AST have 6 each, IO have 5 each, N has 4, FLR have 3 each, DHW have 2 each, everything else has 1).

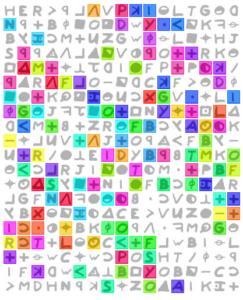

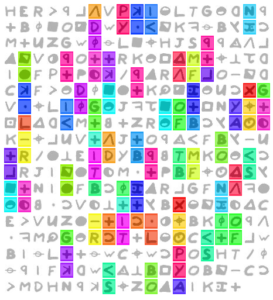

Z340: 340 symbols, from a set of 63. [Hence symbols/textsize is 18.5%, a fair bit higher than the Z408’s 13.3%]

Z32: 32 symbols, from a set of 30.

Z13: 13 symbols, from a set of 8.

It would be very tempting to suspect (as many people have) that the Z340 is ‘therefore’ just the same as Z408 but with 39% more homophones. Yet a problem with this popular hypothesis is that it should be well within range of automated homophone solvers, and to date they haven’t managed to make any impact.

A second problem is that the kind of homophone cycles that so characterized the Z408 seem to be largely absent in the Z340: and yet because the Zodiac Killer would not have had any clue that these were a technical weakness of his system, it seems unlikely to me that he would have adjusted his system to work around a weakness that he didn’t actually know was a weakness.

A third problem is that the Z340 has a fair number of asymmetries that don’t fit the it’s-a-straight-homophonic-cipher model. For example, lines 1-3 and 11-13 have (as Dan Olson pointed out some years ago) almost no character repeats.

There are yet other asymmetries: for example, while 63 different symbols appear in the top ten lines, only 60 appear in the bottom ten lines. And there’s the mysterious ‘-‘ shape at the start and end of line 10: and the odd-looking “ZODAIK” sequence on line 20.

One final asymmetry: the ‘+’ shape seems to function differently in the top and bottom halves – it is often preceded by ‘M’ in the top half, but never preceded by ‘M’ in the bottom half.

How does assuming the Z340 is a pure homophonic cipher explain any of these behaviours, let alone all of them?

Lines 1-3 and 11-13, revisited

I keep coming back to the 1-3 and 11-13 property as mentioned here. I think it’s important to say that Dan Olson’s conclusion (that “lines 1-3 and 11-13 contain valid ciphertext whereas lines 4-6 and 14-16 may be fake”) seems likely to be landing a little bit wide of the mark.

To me, this same property of these lines implies (a) that the homophonic versions for each letter were probably used in pure sequence here, but also (b) the homophone cycles were somehow ‘reset’ after ten lines (i.e. the homophone cycles all started again at the start of line eleven). And perhaps also that any characters repeated in the first three lines are rarer characters, rather than the homophone-friendly ETAOINSHRDLU etc.

It might even be that the Zodiac Killer kept on adding homophones as he constructed the cipher UNTIL he had three lines’ worth of essentially unique homophones: that is to say, that the three line blocks in 1-3 and 11-13 are how his system made the choice of the number of homophones, rather than as a consequence of the number of homophones he chose. Nobody has yet (to my knowledge) satisfactorily explained where he came up with his homophonic allocation for Z408: certainly, searching for this in crypto books hasn’t yielded any likely candidates.

Could it be that the Zodiac Killer worked backwards from his actual Z408 ciphertext to determine the number of homophones, rather than worked forward from the number of homophones to the ciphertext?

—

Update: I received the following off-line comment from David Oranchak, but thought it better to update it within the post itself…

Nick, there are a few other seemingly rare phenomena that can be observed in Z340. I’m curious what you think of them.

The first is the pivots:

http://zodiackillerciphers.com/wiki/index.php?title=Encyclopedia_of_observations#The_.22Pivots.22

Those kinds of patterns are difficult to arise by chance, so they are suspected to be some sort of feature of the encoding scheme.

Z408 is littered with repeating bigrams but Z340 seems to have fewer than would be expected via normal homophonic encipherment of a plaintext in a normal reading direction. However, the bigrams show up again if you consider a periodic operation on the cipher text:

http://zodiackillerciphers.com/wiki/index.php?title=Encyclopedia_of_observations#Periodic_ngram_bias

The count of 25 repeating bigrams jumps to 37 or 41 or even higher, depending on the periodic operation applied to the cipher text. Here is a tool that illustrates the various operations:

http://zodiackillerciphers.com/period-19-bigrams/

You’ve already identified the seemingly rare phenomenon of rows that lack repeating symbols. There are 9 such rows. In 1,000,000 random shuffles of Z340, none had that many rows. In fact, the best that was found was 8 rows which occurred in only 12 of the shuffles.

Your “M+” asymmetry observation seems to fit in with the general observation that repeating bigrams are phobic of certain regions of the text. The lower left, for instance, seems to hate bigrams: http://zodiackillerciphers.com/images/z340-repeating-bigrams.png

Another really strange observation is the distribution of non-repeating string lengths. For each position of Z340, measure how far you can read forward without encountering a repeating symbol. You end up with a string with unique sequences of length L. Jarlve found that for Z340, there is a peak of 26 occurrences of unique sequences of length 17 (which happens to be the width of Z340). It is really interesting that in random shuffles, this phenomenon is only observed on the order of one in a billion shuffles.

Finally, I would recommend that anyone interested in this topic should check out this thread on morf’s Zodiac forum: http://zodiackillersite.com/viewtopic.php?f=81&t=3196 Especially the more recent posts on the latter pages. “Jarlve” and “smokie” in particular are doing fantastic work exploring various transcription schemes that could explain the various curious features of Z340 (in particular, the relationships between periodic bigrams and transposition schemes).