One of the (frustratingly small) number of art history leads the Voynich Manuscript’s author dangles before our eyes is the balneology part of Q13 (“quire 13”). Specifically, there are two bifolios that depict baths and pools, where the pictures helpfully allow us to reconstruct what the page layout originally was:

84r/84v – contains Q13’s quire number (which should be at the back for binding)

78r/78v – contains left half of a two-page bath picture (should be centrefold)

81r/81v – contains right half of a two-page bath picture (should be centrefold)

75r/75v

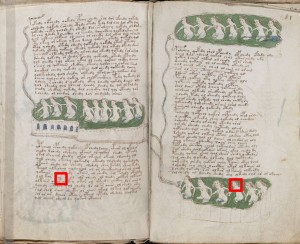

The centrefold originally looked like this (my red boxes highlight a paint transfer):-

This codicological nuance demonstrates that Q13’s quire number was added after the bifolios had been scrambled, because the page it was written (f84v) on was originally inside the quire, on a bifolio that ended up both flipped and in the wrong position. In “Thc Curse” (pp.62-65), I tried to follow this through to reconstruct the original page order for the whole of Q13.

Fascinatingly, Glen Claston has now raised this whole idea up to a whole different level – he proposes that Q13 was originally two separate (smaller) quires which have been subsequently merged together. According to his reading, the four folios listed above originally formed a free-standing balneological quire (which he calls “Q13b“), while the remaining bifolios form a free-standing medicinal / Galenic quire all on its own (which he calls “Q13a“).

Even though Glen and I disagree on the likely page order of Q13a (apart from the fact that the text-only f76r was very probably the first page, and hence its bifolio was the outer bifolio for the quire) and on its probable content, I have to say that I’m completely sold on his proposed Q13a / Q13b layout (basically, I wish I’d thought of it first – but I didn’t, Glen did). We also agree that because there is no indication at all that f84r was the front page of the quire, there was probably an additional (but now lost) outer bifolio to Q13b in its original state.

Glen also infers (from the apparent evolution of the language between the two parts) that Q13b was made first, with Q13a coming later. Having mulled over this for a few weeks now, I have to say I find this particularly intriguing because of what I believe is a subtle change in quality between the drawings in Q13b and Q13a that strangely parallels the change in drawings between Herbal-A pages and Herbal-B pages.

My key observation here is that whereas Q13b’s drawings appear to be straightforward representations of baths and pools, Q13a’s drawings appear to have layers of rendering and meaning beneath the representational surface: that is, while Q13b is a small treatise on baths, Q13a is a small treatise on something else, rendered in the style of a small treatise on baths. As an example, on f77v you can see something literally hiding behind the central nymph at the top – but what is it?

This closely mirrors what I see in the herbal A & B sections: while Herbal-A pages (from the earliest phase of construction) appear to be representing plants (if sometimes in an obscure way), Herbal-B pages (which were made rather later) appear to be something else entirely made to resemble a treatise on plants.

My current working hypothesis, therefore, is that the representational (if progressively more distorted) Herbal-A pages and the representational Q13b balneological section preceded both the non-representational Herbal-B pages and the non-representational Q13a pages, both of which are disguised to look like their respective predecessor, while actually containing something quite different.

(As an aside, the same kind of mechanism might be at play in the pharma section: there, too, you can see ‘jars’ that seem to be purely representational, together with other things that seem to be disguising themselves as ornate jars. Very curious!)

This has a strong parallel with the way that recent art historians (such as Valentina Vulpi) decomposes Antonio Averlino’s libro architettonico into multiple writing phases: In “The Curse” (pp.106-107), I proposed a slightly more radical version of Valentina’s thesis – that Averlino (Filarete) targeted Phase 1 at Francesco Sforza, Phase 2 at Galeazzo Maria Sforza, and Phase 3 at both Francesco Sforza & Lorenzo de’ Medici. In the case of the VMs, I suspect that some of the difficulties we face arise from broadly similar changes in need / intention / strategy over the lifetime of the construction – that is, that the style of the cipher and drawings probably evolved in response to the author’s life changes.

As far as art history goes, though, Q13b appears to give us a purely representational (if enciphered!) connection with baths and pools – places associated in the Middle Ages and Renaissance with healing. Bathhouses were usually situated in the centre of towns and were used by urban folk: while natural spas and pools were thought to have specific healing powers based on their particular mineral content, were usually in fairly inaccessible places, and tended to be frequented by the well-off at times of ill-health (for you needed resources to be able to fund a party to trek halfway up a mountain).

So… might there be an existing textual source where this (presumably secret) information on baths and spas could have come from?

The main source for medieval balneological information was Peter of Eboli’s much-copied De Balneis Puteo (which was hardly a secret): when I wrote “The Curse”, the two main Quattrocento balneological discussions I knew of were by Antonio Averlino and by the doctor Michele Savonarola. I also pointed out that that the (now misbound) Q13 centrefold (f78v and f81r) resembles “the three thermal baths at the Bagno di Romana. Of these, the ‘della Torre’ bath was used for showers, the ‘in-between bath’ was used to treat various illnesses and skin complaints; while the third one was more like a women’s spa.” (p.63)

However, I recently found a nice 1916 article online called “Balneology in the Middle Ages” by Arnold C. Klebs. Klebs notes (which I didn’t know) that the fashion for balneology died around 1500, fueled by a widespread belief that baths and spas were one of the causes of the spread of syphilis. Errrm… that would depend on what you happened to be doing in the baths (and with whom), I suppose. Here are some other fragments from the last few pages of Klebs’ article which might well open some doors:

In Giovanni de Dondis we usually hail the early apostle of exact balneology. Whatever his right to such honour may be, it must be mentioned that it rests on his attempt to extract the salts of the thermal of Abano.

Gentile da Foligno (died 1348), […] a great money-maker and promoter of the logical against the empirical method in medicine. He wrote a little treatise on the waters of Porreta, the chief interest of which may be found in the fact that it was the first to appear in print (1473).

Ugolino Caccino, of Montecatini (died 1425). He came from that thermal district not far from Florence, in the Valdinievole, which has still preserved its ancient reputation as a spa. Evidently he was a man of broad and open-minded scholarship, who in his treatise on all the Italian spas, the first thorough one of the kind, gives the results of his own personal observations, stating clearly when he is reporting from the information of others.

Matteo Bendinelli (1489) sums up for them all, in his treatise on the baths of Lucca and Corsenna,…

Michele Savonarola, representing Padua and the new school of Ferrara. To him European balneologrv owes the most ambitious work on the mineral springs of all the countries.

De Balneis omnia quae extant,” Venice, Giunta, 1553, fol., 447 leaves. This fine collection, the first text-book on balneology, offers to the interested student a mine of information.