I’ve been going through yet more of the (digitised) papers in the Smithsonian’s Captain George Henry Mills Collection, and have more to share about Captain Charles Kendall and NAS Lakehurst history.

The CNATE Succession

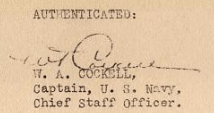

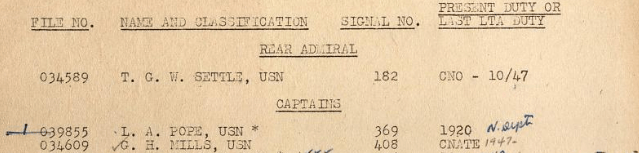

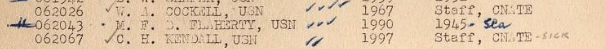

At the start of the period in question (1945-1950), the base commander at NAS Lakehurst was Vice Admiral Charles (‘Rosey’) Rosendahl. However, when ill health forced Rosendahl to retire early, the base was temporarily run by Captain William Arthur (‘Art’) Cockell, who then handed over to Rear Admiral Thomas (‘Tex’) Settle. Settle was in turn replaced by George (‘Shorty’) Mills, who held the post of CNATE to mid-1949.

We can see much of this from a clipping from “The Bag Vet” (Number 1, Vol 1, 1st September 1946, p.1), an airship “News Sheet For All Vets of Blimpron 14”, which, along with all its where-are-they-now and would-you-like-a-job-flying-a-Howard-Hughes-blimp articles, also included airship-related news from various NAS bases such as Lakehurst:

(By way of explanation: a “blimpron” was a “blimp squadron”, Blimpron 14 was also known as “ZP-14”).

Captain Kendall updates

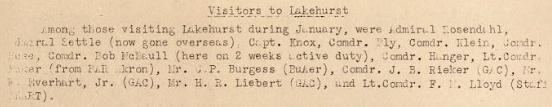

Even though Charles Kendall seems (unlike Rosendahl and Mills) not to have subscribed to The Bag Vet, a few news items relating to him do appear there. For example, in The Bag Vet, Jan 15th 1947:

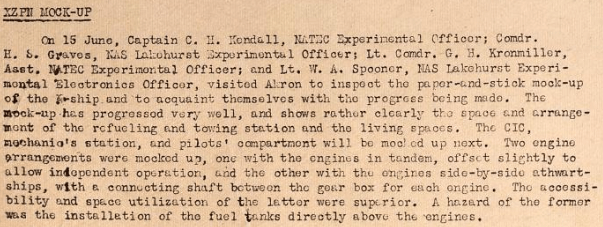

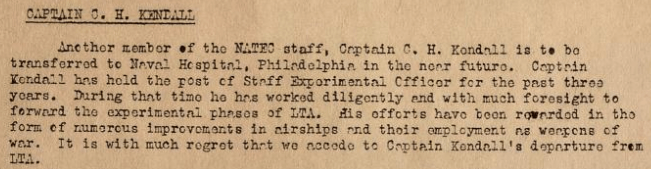

Decoding the Navy acronyms, “C.O. ZP12” was “Commanding Officer of Blimpron ZP-12”: this was the blimp squadron that covering the Atlantic during WWII. “X.O” was “Executive Officer”, who was normally the Number Two on a given base. So it seems from this that Kendall started as Executive Officer under Tex Settle, but then became Experimental Officer at the start of 1947.

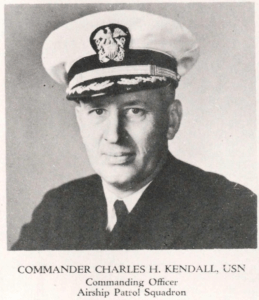

Incidentally, there’s a nice picture of Kendall as C.O. ZP-12 in “United States Naval Air Station Lakehurst New Jersey – A Photographic Essay”, a copy of which is in the George Mills Collection:

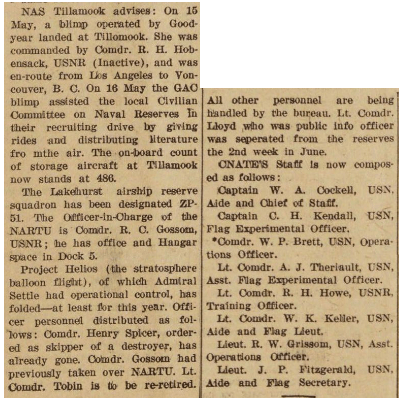

The Bag Vet (Vol. 1, Number 5, 1st Nov 1947) mentions the demise of Project Helios (note that Commander Henry Calvin Spicer Jr was for a while the designated pilot for Project Helios):

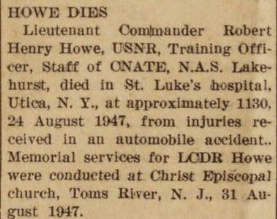

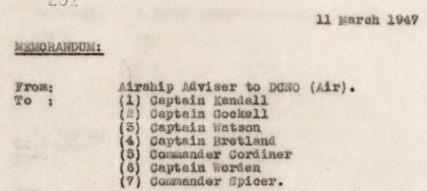

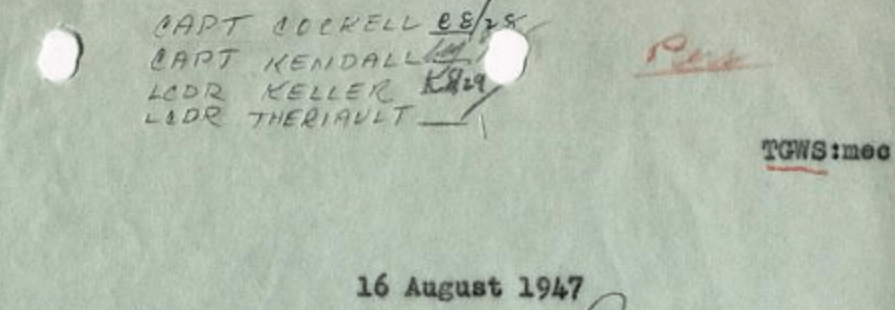

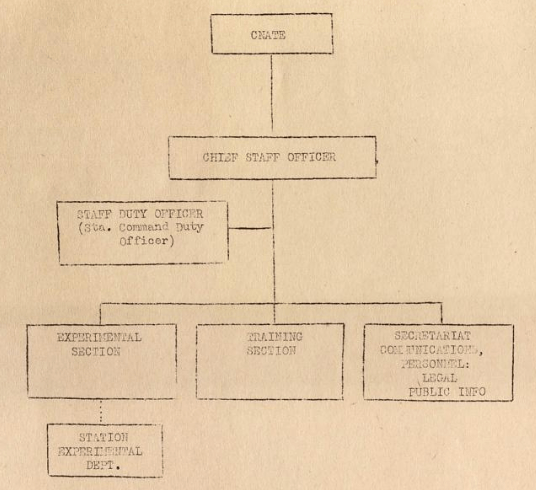

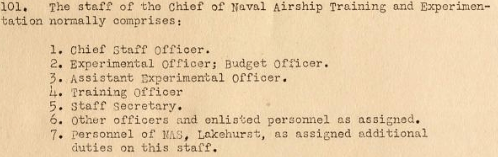

So, at some point in 1947, Captain Art Cockell was SDO NAS Lakehurst, Captain Charles Kendall was Experimental Officer, and Lt. Commander Alcide Theriault was Assistant Experimental Officer beneath Kendall. However, we can date this organisational change to before 24th August 1947, because that sadly was when Lt. Commander Howe (“Training Officer” above) died in an automobile accident:

Incidentally, in a US Navy context, a “Flag Officer” means a commissioned officer senior enough that they are entitled to fly a flag at the place they exercise their command. While this normally applies to rear admirals or higher, it can also apply to someone who has commanded a squadron of vessels. Yet in such cases, this normally only applies for up to a couple of years until a suitable promotion (normally to rear admiral) can be put in place.

So it would seem that in 1947, Captain Charles Hansford Kendall was very close to becoming an Admiral in the US Navy, a rank his older brother Henry Samuel Kendall had previously reached. It therefore seems likely to me that Kendall would have taken on the role of Experimental Officer at NAS Lakehurst only on a temporary basis: at that time, he was surely headed for a bigger role within the Navy before too long.

Where next in the archives?

While it has been helpful going through the (fully-digitised) George Mills Collection at the Smithsonian, and frustrating looking at the finding aid for its (entirely undigitised) J. Gordon Vaeth Collection (boo), it left me wondering if I was even looking in the right place.

I think it fair to say that George Mills was more of an administrator who liked LTA, while Vaeth was an airship enthusiast (if not actually a bit of an LTA history obsessive). But both of them were left firmly in the shade by Vice Admiral Charles Rosendahl: following his early retirement, Rosendahl seems to have spent the next 30-odd years writing constantly about airships – from the archives, there seem to be few newspapers or magazines or journals to which he didn’t submit pieces or articles concerning LTA.

And so it is that Charles Emery Rosendahl’s voluminous collection of LTA material at the Special Collections Department, Eugene McDermott Library (at the University of Texas at Dallas) has ended up, without much doubt, as the best place to look for answers to historical questions about airships and US Navy LTA history in general. This contains over 330 boxes of material: there’s a finding aid here.

Why is this so good? For example, whereas the George Mills Collection has a few cherry-picked issues of “The Airship” from NAS Lakehurst, the Rosendahl Collection holds (I believe) every issue from 1944 right through to 1958. Similarly, Rosendahl has Vol. 2 Number 6 of The Bag Vet (Mills only goes up to Number 5), along with a whole load of rare LTA newsletters that it would seem nobody else has ever heard of.

Even though I think I have already unpicked much of the raw history I was hoping to find, the answer to the thorny question of what actually happened to Charles Kendall still evades me. Yet there seems a good chance that the answer will be found in the Charles Rosendahl Collection, either in “The Airship” or The Bag Vet (Vol. 2 Number 6), if only I could find a way to look there…