If, like me, you’ve been looking for a nice guide to illustrated manuscripts in the Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg’s Cod. Pal. Germ. collection for a while, you’re in for a bit of a treat here. 🙂

German librarian / book historian Hans Wegener’s (1927) “Beschreibendes Verzeichnis der deutschen Bilder-Handschriften des späten Mittelalters in der Heidelberger Universitäts-Bibliothek” (which you can download from UB Heidelberg here) runs through a (mostly) chronological series of illustrated manuscripts from the library, discussing each one’s writer(s) and (usually unnamed) illustrator(s).

(For reference, the para at the top of its p.10 was where Hans Wegener asserted that the illustrator of Cod. Pal. Germ. 530 also drew the pictures for Staatsbibliothek Eichstätt MS 212, as I mentioned in my last post.)

The easiest way to view all the illustrations is to use UB Heidelberg’s HeidICON tool (there’s a link on the left of each CPG page). There, you can jump straight to a grid of illustrations in that manuscript, i.e. clicking on a thumbnail brings up the full-size picture on the right-hand side.

I went through all the drawings from 1400 to about 1470, and have pasted in some of the most interesting drawings. Enjoy!

1300 to 1400 (for completists only)

Cod. Pal. Germ. 164 – Sächsisches Lehnrecht, Obersächsische Hs., Um 1320

Cod. Pal. Germ. 167 – Landrecht des Sachsenspiegels und des Schwabenspiegels. Niederdeutsche Hs. Hälfte XIV. Jahrh.

Cod. Pal. Germ. 341 – Sammlung kleinerer Gedichte. Oberdeutsche Hs. Mitte XIV. Jahrh.

Cod. Pal. Germ. 53 – Schwabenspiegel. Oberdeutsche Hs. Ende XIV. Jahrh.

1400 (Various)

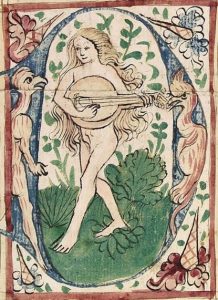

Cod. Pal. Germ. 329 – Hugo von Montfort: Gedichte und Lieder. [Bayrische Hs. Um 1400.] (just initials)

Cod. Pal. Germ. 14 – H. von Mügeln: „Der meide kränz”. [Bayrische Hs, 1407.] (just initials)

Cod. Pal. Germ. 336 – Enenkels Weltchronik. [Bayrische Hs, Um 1410.]

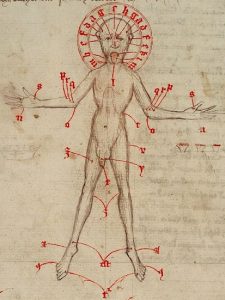

Cod. Pal. Germ. 5 – Wahrsagebuch. [Mitteldeutsche, wohl rheinfränkische Hs, 1400-1420. (Just one drawing)

Cod. Pal. Germ. 330 – Thomasin von Zirklaere: Wälscher Gast. [Bayrische Hs, 1410-1420.]

I discussed cpg330 in this recent post, but it has other interesting images (note that HeidICON has no entries for this!):

Cod. Pal. Germ. 794 – Boner: Edelstein. [Bayrische Hs. 1410-1420]

Die elsässische Werkstatt von 1418.

Before Diebold Lauber’s famous workshop, there was another (unnamed) workshop in Alsace, usually referred to as the Werkstatt von 1418.

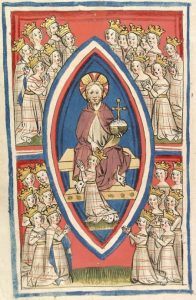

Cod. Pal. Germ. 27 – Otto von Passau: Vierundzwanzig Alte. [Elsässische Werkstatt von 1418. 1418.]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 144 – Heiligenleben. [Elsässische Werkstatt von 1418.] (Lots of saints being killed, if you like that kind of thing.)

Cod. Pal. Germ. 403 – Heinrich von Veldeke: Eneide. [Elsässische Werkstatt von 1418.]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 371 – Lanzelot. [Elsässische Werkstatt von 1418. 1420.] (only two images at the front)

Cod. Pal. Germ. 365 – Ortnit. [Elsässische Werkstatt von 1418. 1420.] (Only two drawings)

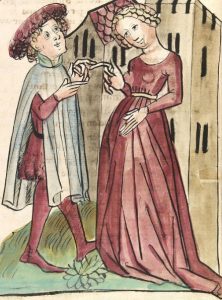

Cod. Pal. Germ. 323 – Rudolph von Ems: Wilhelm von Orlenz. [Elsässische Werkstatt von 1418. 1420]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 359 – Rosengarten und Lucidarius. [Elsässische Werkstatt von 1418. Um 1420.] (Not particularly interesting drawings)

Other Stuff

Cod. Pal. Germ. 432 – Speculum humanae salvationis. [Mittelrheinische Hs. 1420-1430.]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 471 – Hugo von Trimberg: Renner. [Bayrische Hs, 1431.]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 148 – Biblia pauperum [ Bayrische Hs, 1430-1440] und Brevier [Bayrische, wohl Eichstätter Hs, Um 1450]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 7 – Wahrsagebuch [Bayrische Hs, 1430-1440]

Die Werkstatt des Diebolt Lauber in Hagenau.

I have, of course, discussed Diebold Lauber’s workshop a good number of times before. And UB Heidelberg has plenty of Lauber mss!

Cod. Pal. Germ. 362 – Flore und Blancheflor [Werkstatt des Diebolt Lauber in Hagenau, 1430-1440]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 324 – Dietrich und seine Gesellen. [Werkstatt des Diebolt Lauber in Hagenau, Um 1440]

(The next five items form “Deutsche Bibel in 5 Bänden”.)

Cod. Pal. Germ. 19 – Die Bücher Mose, Josua und Richter [Werkstatt des Diebolt Lauber in Hagenau, Um 1440] (not very interesting drawings)

Cod. Pal. Germ. 20 – Bücher der Könige und Paralipomenon I und IL [Werkstatt des Diebolt Lauber in Hagenau, Um 1440] (also not very interesting drawings)

Cod. Pal. Germ. 21 – Die Bücher Esra, Nehemia, Tobias, Judith, Esther, Hiob, Psalter, Parabole Ecclesiastes, Cantica, Sapientia und Ecclesiasticus. [Werkstatt des Diebolt Lauber in Hagenau, Um 1440] (again, pretty dull)

Cod. Pal. Germ. 22 – Die Bücher jesaia, Jercmia, Baiiieli, Hesekiel, Daniel und die zwölf kleinen Propheten. [Werkstatt des Diebolt Lauber in Hagenau, Um 1440] (didn’t work for me at all)

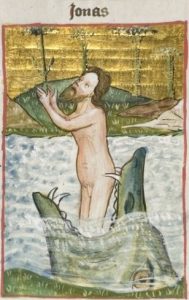

Cod. Pal. Germ. 23 – Das Neue Testament [Werkstatt des Diebolt Lauber in Hagenau, Um 1440] (nope, the whole set failed to press my buttons)

Cod. Pal. Germ. 300 – Megenberg: Buch der Natur. [Werkstatt des Diebolt Lauber in Hagenau, 1440-1450]

Cpg300 contains an old pair of friends, but some other stuff too:

Cod. Pal. Germ. 149 – Sieben weise Meister und die Chronik des Martin von Polen. [Werkstatt des Diebolt Lauber in Hagenau, Um 1450]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 339 – Parzival. [Werkstatt des Diebolt Lauber in Hagenau, Um 1450]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 137 – Martin von Polen: Chronik. [Werkstatt des Diebolt Lauber in Hagenau, Um 1460] (dull as ditchwater, unless you really like grinding your way through endless unconvincing drawings of popes)

More Other Stuff

Cod. Pal. Germ. 311 – Megenberg: Buch der Natur [Mittelrhemische Hs, 1450-1460] (Has a nice catoblepas)

Cod. Pal. Germ. 438 – Gedieht von den zehn Geboten, der Bulie, der Beichte und den sieben Todsünden. [Mitteldeutsche Hs., 1450-1460]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 314 – Boner: Edelstein. [Augsburger Hs, Um 1445]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 322 – Otto von Passau: Vierundzwanzig Alte. [Oberrheinische Hs, 1457]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 644 – Medizinische Traktate [Oberdeutsche Hs, 1450-1460] (Thirty pictures of physicians looking at flasks of urine. Nice.)

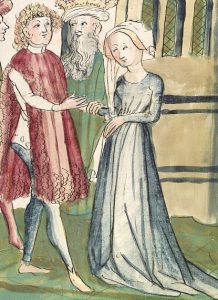

Cod. Pal. Germ. 4 – Rudolf von Ems: Wilhelm von Orlens [Augsburger Hs, 1458]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 147 – Lanzelot [Mitteldeutsche Hs., Mitte XV. Jahrhundert]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 344 – Gedichte (“Von dem Eilenden Buoben”, Spruchgedicht von der Minne und dem Pfennig und Spruchgedicht vom Streite

zweier Frauen über Liebe und Leid der Minne) [Oberrheinische Hs, Um 1459]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 60 – Deutsche Bibel, Brief des Juden Samuel, Ars moriendi. Legende des hl. Patricius und die Legende des hl. Brandon. [Oberdeutsche Hs, Um 1460]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 86 – Boner: Edelstein. [Bayrische Hs, 1461]

Sal. VII. 114. Belial [Oberdeutsche Hs, Um 1460]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 346 – Tristan [Seeschwäbische Hs., Um 1460]

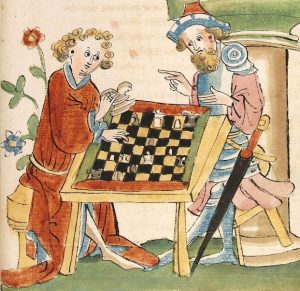

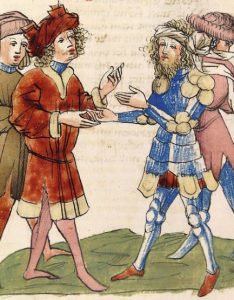

Cod. Pal. Germ. 463 – Jakob von Cessolis: Schachzabel [Oberschwäbische Hs., 1463]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 795 – Belial [Oberdeutsche, wohl Augsburger Hs, Um 1470]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 320 – Thomasin von Zirklaere: Walscher Gast [Schwäbische Hs, Um 1470]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 646 – Passion. [Oberdeutsche, wohl Augsburger Hs. 1470]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 76 – Ackermann von Böhmen [Schwäbische Hs. Um 1470]

Cod. Pal. Germ. 111 – Legende vom hl. Mauritius und Legende vom hl. Meinrat. [Schwäbische Hs., Um 1470]

Hans Wegener continues his book with CPG manuscripts from Ludwig Hennfflin’s Werkstatt, but this is now well out of our window of interest, so I’ll stop here. 🙂