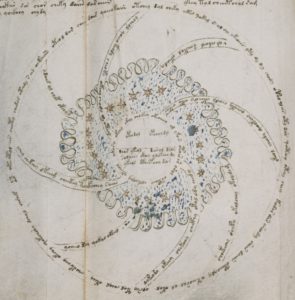

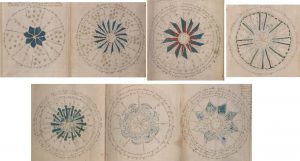

Since posting about Voynichese’s strange single leg gallows behaviours a few days ago, I have continued to think about this topic. On the one hand, it’s clear to me how little of any genuine substance we actually know about how they work; and on the other, I’ve been wondering how I can start some broadening conversations about them (by which I mean ones that ask more questions than they answer).

As today’s experimental contribution, I’m going to write a post listing a load of the questions I have in my head to do with single leg gallows but without really trying to answer any of them. I can’t tell how this will work, but here goes regardless. 🙂

Incidentally, for anyone who wants to run their own statistical experiments on single leg gallows, I would strongly recommend using Herbal-B + Q13 + Q20 as their basic test corpus, because I’m acutely distrustful of any Voynich stats that combine Currier A and Currier B. Even though I’m basically doing the latter here. 😉

Questions: final flourish

Rather than finishing with a second vertical leg on the right hand side, single leg gallows instead cross over the left hand leg and finish with a slight flourish to the left. This final flourish can be (1) short, (2) long and straight, or (3) long and curved (i.e. finishing with something like an EVA c-shape).

- Have the variations in the finishing flourish of single leg gallows been catalogued and/or transcribed?

- Are these variations found uniformly throughout the manuscript, or are they strongly correlated with the various scribal hands (as recently proposed by Lisa Fagin Davis)?

- If they have been transcribed, is each flourish type statistically associated with any neighbouring textual behaviours (e.g. contact tables, etc)?

Questions: followed by EVA e?

One huge difference between single leg gallows and double leg gallows is that non-struckthrough single leg gallows are very rarely followed by EVA e. If you count strikethrough gallows separately from normal gallows, the statistics are quite, umm, striking:

- k:ke = 9758:3809 = 39.03%

- t:te = 5802:1748 = 30.13%

- p:pe = 1383:5 = 0.36%

- f:fe = 416:3 = 0.72%

- ckh:ckhe = 876:242 = 27.63%

- cth:cthe = 905:190 = 20.99%

- cph:cphe = 212:64 = 30.19%

- cfh:cfhe = 73:14 = 19.18%

Moreover, looking at the eight instances in Takahashi’s transcription where EVA p and EVA f are followed by EVA e, I suspect that many of these may well be transcription errors (i.e. where Takahashi should have instead written EVA pch / fch).

Hence it seems to me that Voynichese has a secret internal rule that almost completely forbids following EVA p and EVA with EVA e. This is a massively different usage scenario from EVA t / EVA k (which are followed by EVA e 39.03% and 30.13% of the time respectively).

OK, I know I said I was only going to ask questions in this post, but looking at these numbers afresh, I can’t help but speculate: might it be that EVA p/f are nothing more complex than a way of writing EVA te/ke?

- Has anyone looked closely at the eight places where pe/fe occur?

- Why is there such a huge difference between pe/fe and the other six gallows?

- Might this be because EVA p and EVA f are optional ways of writing EVA te and EVA ke?

- Has anyone considered this specific possibility before?

- How similar are the contact tables for EVA te/ke and EVA p/f?

Questions: Followed by EVA ch?

Similarly, comparing the stats for instances where gallows are followed by the (almost identical looking) EVA ch glyph reveals more differences:

- k:kch = 9758:1074 = 11.01%

- t:tch = 5802:975 = 16.80%

- p:pch = 1383:733 = 53.00%

- f:fch = 416:190 = 45.67%

- ckh:ckhch = 876:5 = 0.57%

- cth:cthch = 905:3 = 0.33%

- cph:cphch = 212:1 = 0.47%

- cfh:cfhch = 73:0 = 0.00%

Here, we can see that both p and f are followed by ch about half the time (53% and 45.67% respectively), which is significantly more than for k and t (11.01% and 16.80% respectively).

At the same time, the dwindlingly tiny number of places where strikethrough gallows are followed by ch (only nine in the whole manuscript) again raises the question of whether these too are either scribal error or a transcription error.

As an aside, I previously floated the idea here that c + gallows + h may have simply been a compact (and possibly even playful) way of writing gallows + ch, which would be broadly consistent with these stats.

- Is there anything obviously different about Voynichese words containing EVA kch / tch and Voynichese words containing EVA pch / fch?

- Has anyone looked in detail at the eight instances where strikethrough gallows are immediately followed by EVA ch?

- If you remove paragraph-initial p- words from these stats, do the ratios for p:pch and f:fch settle down closer to the ratios for k:kch and t:tch?

- How similar are the contact tables for EVA tch/kch and EVA cth/ckh?

- How similar are the contact tables for EVA tech/kech and EVA pch/fch?

Questions: Double Leg Parallels?

Some researchers (perhaps most notably John Tiltman, if I remember correctly) have wondered whether EVA p / f might simply be scribal variations of (the much more common) EVA t / f.

- Beyond mere visual similarity, is there any actual evidence that supports this view?

- I would have thought that the pe/fe stats described above would have meant this was extremely unlikely, but am I missing something obvious here?

Questions: Paragraph-Initial?

Yes, single-leg gallows (mainly EVA p) are very often found as the first letter of the first word of paragraphs. But…

- How often do single leg gallows (and/or strike-through single leg gallows) appear in the first word of a paragraph but not as the very first letter of the word?

- Do these these paragraph-initial -p-/-f words show any pattern?

- Are there structural similarities between paragraph-initial p-/f- words and other paragraph-initial?

- Might there be some kind of numbering system embedded in paragraph-initial p- words (particularly in Q20)?

Questions: vs Double Gallows?

Yes, single-leg gallows are to be found mainly in the top line of paragraphs, but that’s imprecise and unscientific.

- Are the number of gallows characters (whether single or double) per line roughly constant for both the first lines of paragraphs and for the other lines of paragraphs?

- Do these statistics change between sections?

And Finally…

Please feel free to leave comments asking any other single leg gallows questions, I’m sure there are plenty more that could sensibly be added to this page. 🙂

All answers happily received too. 😉