And yes, you have me to blame for it.

So here goes…

It all starts in Frascati…

Today’s story begins in the Voynich Centenary Conference back in 2012, with – as I recall – a bunch of Voynicheros crowding around my Jean-Claude Gawsewitch Voynich Manuscript photo-facsimile. With the pages turned to some of the Q13A (medical) pages, Rene Zandbergen remarked that some of the pictures there looked eerily like slightly-disguised medical drawings.

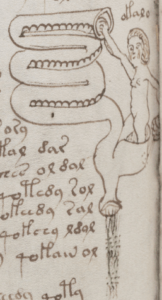

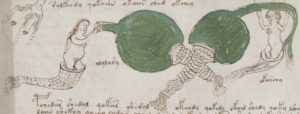

The two diagrams I specifically remember Rene mentioning that day were (a) the “intestines” one:

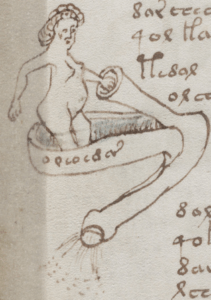

And… (b) well, this piece of the male anatomy (which nobody can deny has a tube running through it):

Rene himself didn’t claim to have been the first to point out these similarities, but rather said that he had heard them mentioned many years before. As normal, a diligent trawl of the old Voynich mailing list archives would probably reveal more lineage (but it’s not hugely important for the purposes of this post).

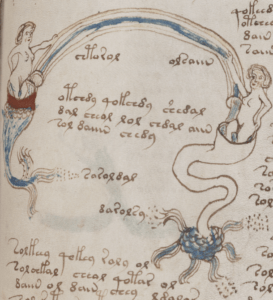

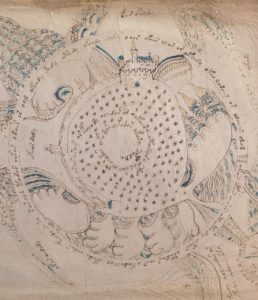

Also, as I’m sure many (if not most) Cipher Mysteries readers know, countless Voynich theories have been constructed around the notion that Q13 (Quire 13) has some kind of connection with the female reproductive system, in particular this gloriously mad drawing, with all its oddly misplaced frilly wolkenbanden:

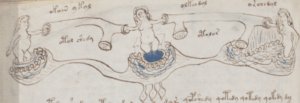

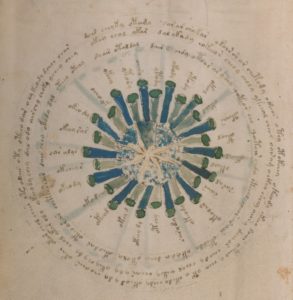

A few pages further on, there’s also a curious pulsating blue brain thing (I have no idea what this means, and I don’t know if anyone has yet looked for visual parallels for it in 15th century manuscripts, perhaps it’s the kind of thing Koen Gheuens would like to take a stab at?):

But you mentioned “testicles”, right?

I did. And so (at last) here’s the specific Voynich image from Q13 that I’m wondering about.

Putting aside the whole ‘nymph’ issue to one side, what – you might reasonably ask – has got into me to wonder if this specific veiled drawing somehow represents a gigantic pair of testicles?

Benedetto Reguardati

A few posts back, I gave a list of authors who wrote small works on thermal baths in the first half (or so) of the fifteenth century. One of those authors was Benedetto Reguardati, a doctor who spent many years attending to the newly-installed Sforza Duke’s family in Milan (and environs).

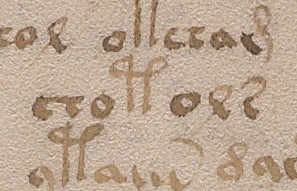

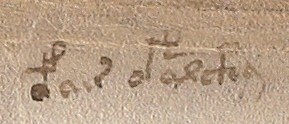

He wrote a number of small treatises, including a pharmacopoeia that can be found in Firenze, Biblioteca Riccardiana, MS Ricc. 818. This commences (on fol. 2r) with:

Emplastrum optimum ad inflationem testiculorum…

i.e. “the best plaster [normally a paste or salve applied to the skin on a piece of linen or leather] for swollen testicles…“

Sadly, I don’t have access to a transcript of Reguardati’s pharmacopeia (merely its incipit), so don’t know how this continues. Obviously this would be a prime research target for anyone who wants to chase after 15th century recipes for enlarged testicles.

Medieval Writings on Testicles

(By which I don’t actually mean tattoos.)

Though I haven’t yet stumbled upon a literature specifically covering medieval recipes for testicular complaints, it would perhaps be unwise to assume such a niche thing doesn’t exist. Even a fairly cursory search revealed that most testicle-related medical mishaps and scenarios were written about in the Middle Ages.

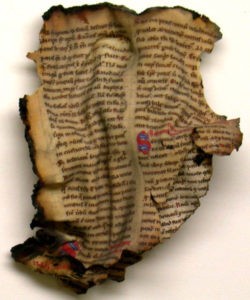

For example, Arnald of Villanova wrote about testicular hernias; Thorndike (1936) mentions a medical “Experimenta” found in “fols. gr, col. i-gv, col. 2 (older numbering, 1-7) of Vatic. Palat. lat. 1174, a vellum ms of the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century with alternating red and blue initials“, that has a section name “Ad tumorem testiculorum”. Similarly, Simon of Genoa discussed testicular abscesses in his medical dictionary.

John Bradmore also included several brief sections on testicular complaints in his “Philomena” (see Lang 1998):

- 70v 40 de Apostematibus Testiculorum

- 71r 41 de Apostemate hernia Aquosa testiculorum

- 72r 42 de Apostemate hernia ventosa testiculorum

- 73r 43 de (Apostemate) hernia Carnosa et varicosa testiculorum

- 73r 44 De Apostemate hernia humorali testiculorum

Also: p.196 of this book mentions Bodleian MS Selden B35 (circa 1465) as listing “Ydicelidos” = “i. habens testiculos inflatos”, with a footnote mentioning Simon of Genoa’s “Clavis Sanationis”: “Hydrocelici vel ut grecus ydrokilis, dicuntur qui aquam habent circa testiculos in oscum”.

So I think it should hardly be a surprise to find Reguardati writing about salves for swollen testicles. But it turns out that he was far from the only one.

Medieval Swollen Testicles

However, what did surprise me was that I was able to find a good number of different medieval recipes for swollen testicles.

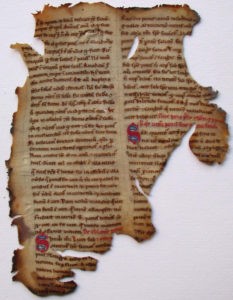

Egritudines Tocius Corporis, written by a physician names Copho in the second half of the 11th century, includes the following section:

De inflatione testiculorum — Ad inflationem testiculorum sine materia, interiora labarum trita optime coquas, et ut comeduntur calida superponus; vel, quod melius est, galbanum in vino coque et cola et in colatura spongiam marinam diu bullias et superponas; vel ebuli seu sambuci summitates diu in vino bullias, et postea cum axungia teras, et hoc totum super testiculos ponas. Si autem maxima duricia sit in testiculis duas pelliculas incide et in tercia stamina pone, et tam diu teneat durice materia que duriciem operatur recedut.

According to Monica H. Green, four versions of the Trotula include an extra section “Ad inflatione testiculorum”:

- 34: Harley 3407

- 70: Digby 29

- 74: Wood empt. 15 (SC 8603)

- 80: New College, 171

I don’t have access to the full text of this section, but it begins:

Ad testiculos inflatos fomentum, accipe maluam, absinthium, uerbenam, bismaluam, cassillaginem, arthimesiam, caules.

13th century Portuguese physician Pedro Hispano’s (Petrus Hispanus) Liber de conservanda sanitate (book by Maria Helena da Rocha Pereira (1973), p.233) has a Chapter XXXV, “De inflatione testium”:

- Si testes inflentur, farina fabarum distemperata cum suco ebuli et oleo communi statim inflationem soluit. Dyascorides.

- Item idem faciunt folia ebuli uel parietarie torrefacta.

- Item idem faciunt folia ebuli et sambuci. Hoc ego.

- Item fimus caprinus cum uino solutus omnem tumerm soluit, Kyrannus.

- Item folia et semen iusquiama trita cum uino et emplastrata omnem tumorem soluit. Macer.

- Item betonica trita et cocta in uino et apposita dolorem et tumorem aufert testiculorum. Dyascorides.

(Note that da Rocha Pereira also includes a quite different version of that same basic chapter in a footnote.)

From Guillem de Béziers (fl. ~1300), we have another recipe “Contra inflationem testiculorum” (on. p.27):

Item. Contra inflationem testiculorum. Fiat primo subfumigium de aqua calida ad apertionem pororum et postea immittatur agrippa, deinde fiat emplastrum de fimo caprino et sepo arietino et thure, et ad ulti[mu]m minutionem vene sophene fac aperire interiori et sic multi curati sunt.

“Three Receptaria from Medieval England” (Hunt & Benskin) includes a couple of items:

- p.26: [207]: Uncore ad inflacionem testiculorum: Recipe malvam, artemisiam, jusquiamum, et caules veteres. Et si non potes habere hec omnia, accipoantur absinthium et malve tantum, et decoquantur et in illa decoctione epithimentur testiculi.

- p.27: [210]: Item paritoria frixa in patella et testiculis superposita removet inflationem testiculorum.

Thoughts, Nick?

Books on baths and medicine were often bound together, so suggesting that the Voynich Manuscript’s Q13 might well contain both balneological and medical bifolios should cause no great tremors. And indeed the bifolios do – as Glen Claston pointed out many years ago – seem to be thematically divided between balneo and medical (in some way).

If you accept this is right, then the idea that a late medieval medical book like this might contain a short section on swollen testicles is surely not a huge stretch, given the number of different sources listed above that contain recipes or treatments for the same.

Might one of these recipes – or something very much like them – be the plaintext for some of the text on f83v? It’s a pretty good challenge, and definitely not a load of balls. 😉