It’s a hard thing to admit, but I think the Voynich Manuscript tells us much more about History – and specifically about historical proof – than History tells us about the Voynich Manuscript.

Even though we have accumulated so much micro-knowledge about the Voynich (by which I mean how its ‘language’ works, and even – to a certain extent – how it was made and owned), we still have almost no genuine macro-knowledge about it at all. For all the long list of suggestive details, our Voynich knowledge in toto is little more than a forensic desert (and not obviously different to that surrounding the Somerton Man), one that remains so wide that none may cross it and live.

For all Rene Zandbergen’s accumulated provenancing, for all his patient and informed historical nuancery, teasing single strands out of Kircher’s Republic of Letters and weaving them into what are little more than semi-threads, we still know essentially nothing about what Kircher knew of it, or thought of it. We don’t even know if he ever saw the dratted Manuscript, or if the pages (or copies of pages) sent to him by Baresch are still extant in some unknown Jesuit cryptographic archive somewhere. Or (if they are) whether or not they will give us even a flicker of assistance in decrypting Voynichese (based on past form, I suspect they would not).

And yet…

So far, so nothing: but here’s the rub. Even though I’ve long held as a basic research tenet the notion that historians are better equipped at disproving fallacious claims than genuinely proving things, why do you think it is that even after all this time, the Internet is still awash with Voynich claims and theories that make little more than facile, superficial sense?

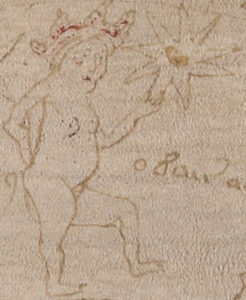

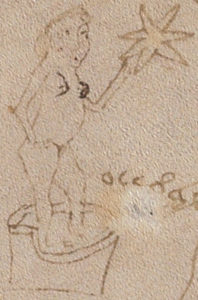

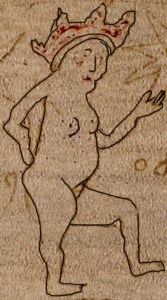

Example #1: why is it that Stephen Bax’s utterly foolish and superficial nine-word theory has found itself promoted to hits #3, #4, and #5 on a Google search for “Voynich” (as of today)? Is it really the case that nobody has noticed that his attempts at reading Voynichese as a natural language fail to explain more than 99.9% of the text, which is almost the very definition of “unsystematic”? Is it really the case that nobody has noticed that you can “read” almost exactly the same number of words by interpreting Voynichese as English?

Example #2: why is that that Gordon Rugg’s shudderingly awful CompSci misreading of Voynichese as a “language” generated by Cardan grilles still has any faint lustre of validity at all? Why is it that I still – all these years on – run into people whose view of the Voynich is not only coloured by this kind of anti-historical claptrap, but also utterly delimited by its faux postmodern stupidity? When will we ever manage to draw a line under this idiocy?

Example #3: why is it that Rich SantaColoma can still get away with miscasting the Voynich Manuscript’s eponymous 20th century finder as its forger? Though he “plays the game well”, if you multiply out all the individual probabilities that he has to bracket out to keep his ball in the court of possibility, it’s hard to see how he can end up with a net likelihood of more than one in a million. All of which is good for his personal position (in that nobody has outright disproved his assertion that Wilfrid Voynich hoaxed his Roger Bacon manuscript), but lousy for the overall discourse, in that he continues to waste everyone else’s time by fighting against whatever they say wherever it happens to run counter to his blessèd sub-one-in-a-million shot.

…and need I honestly extend the same face-palm of logical despair to Guiseppe Bianchi’s recent Youtube video on the Voynich, however lamentable it may be? I sincerely hope not: because disproving it (and the legions of other disappointingly rubbish Voynich non-theories) would be a full-time job, and I already have three of those vying for my as-yet-uncloned time.

The poverty of disproof

Do you see the underlying pattern here? That if Voynich theorists are happy to retreat to the far unpainted corner of possibility (however dwindlingly small a scrap of floor their ill-formed theories leave them to stand on), absolute disproof becomes almost as hard as absolute proof. Moreover, such theorists are then able to take that absence of comprehensive disproof as confirmation that they were somehow on the right track all along – that the inability of others to sumo-wrestle them out of the dohyo justifies their faith in their own worthless position.

In fact, I have become utterly bored with people sending me their worthless non-theories to disprove, because I know that however I respond with, they will then conjure up a counter-example that proves that my disproof was not absolute: and so use the opportunity that yields them to cock a snook at my so-called expertise.

And so I’m left with an uncomfortable conclusion about the Voynich Manuscript and the poverty of disproof: that if it is almost impossible to disprove a mad theory all the while a given loopy theorist can keep dreaming up flimsily etheral counterexamples of possibility, then we’ve all kind of lost before we even begin. At that sad point, the entire discourse has broken down into some kind of demented two-handed game, where one side has an endless supply of imaginative jokers to place on the table.

Ultimately, we’ve now reached a net position where the core discourse about the Voynich Manuscript is so painfully broken that there is almost nothing that can be said about it that will not immediately be opposed by wobbly counterassertions moulded out of outrageously weak possibility.

Specifically, there is almost nothing I can sensibly write about the Voynich Manuscript that Stephen Bax, Gordon Rugg, Rich SantaColoma and Giuseppe Bianchi cannot immediately oppose (sometimes in the same way, or more likely in four wildly different ways), should they wish: which, to me, speaks of a kind of pervasive epistemological collapse. It is as though knowledge’s graph of usefulness plotted against time has historically peaked, and is now steadily declining: that instead of knowing more, we are losing any sense of equilibrium about the internal dynamics that make up good knowledge. The model of knowledge as a medium for slowly accumulating sensible judgments is giving way to a model of rapidly accumulating possibilities, all as bad as each other: and we are all the worse for it.

Right now, nobody seems to grasp that cipher mysteries sit at an oddly hypermodern frontier – and that if we are not careful, this could be the beginning of the end for all knowledge. But nobody seems to care.