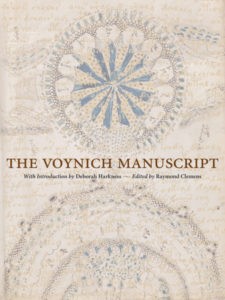

I recently found this page from last year (2015) on Quire 13 (Q13) of the Voynich Manuscript, where the writer asks if anyone knows how the late Glen Claston got to his (2009) idea that the quire was originally written in two halves.

I still have the emails Tim sent me (both dated 7th March 2009), so I thought it would be nice to share them here (only very lightly edited)…

Glen Claston on Quire 13 (Part 1)

[Block quotes here are from my reply to him]

Basic VMS rule – “Major topics always start with a page of text – okay, at least almost always, except when they don’t”.

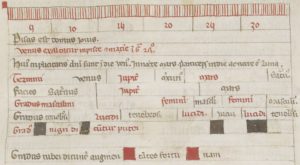

76r is the only full page of text, so it should be the beginning.

76v is medical, and there is only one other medical bifolio to line up with.

80r – medical, and when placed against 76v, the little guy pitching star dust at the top right of 76v works with the line of women on 80r.

80v- the last purely medical page, so all medical pages are now in order with the text page first.

This leaves 79r/v and 83r/83v on the back of this section with the topic of Galenic humors/astral fluxes. The only bifolio that fits in between these that of 77r/77v/82r/82v. Put in that order we transition from medical to biological to Galenic humors.

Per John Grove, 78v and 81r are the center of the quire, identified by the connected drawing across the pages. I agree with that assessment, but the only problem here is that the two remaining bifolios do not deal with topics related to the other three bifolios, and therefore appear to form a separate quire. This has nothing to do with the order of binding, it has everything to do with the flow of connected thought coming from a rational mind.

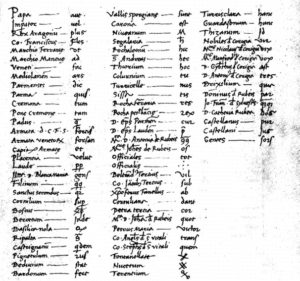

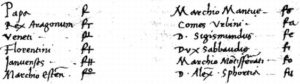

By my judgment, two sections were originally composed, set completely apart from another, and later interleaved. I would have to call them Q13a and Q13b. Here is the order:

Q13a – medical – biological – Galenic

76r/76v – bifolio 2 > medical

80r/80v – bifolio 5 – flipped > medical

77r/77v – bifolio 3 > biological

82r/82v – bifolio 3 > Galenic

79r/79v – bifolio 5 – flipped > Galenic

83r/83v -bifolio 2 > Galenic

Q13b – Balneological

84r/84v – bifolio 1 – flipped > balneological

78r/78v – bifolio 4 > balneological

81r/81v – bifolio 4 > balneological

75r/75v – bifolio 1 – flipped > balneological

There are a couple clues that say Q13b was written after Q13a, but I’d have to do some research to make this claim firm. A scatter plot of these pages from my transcription would be desirable to see if the text separates along the same lines as the visuals do.

Anyway, I’ll look at it a bit more, but spending a few minutes on it and refreshing my memory, this is where I sit on the nature of Q13.

Glen Claston on Quire 13 (Part 2)

Thanks for the notes on Q13. First thing is that I completely agree there is definitely a difference in kind between Q13a and Q13b. For a start, Q13a has nymphs doing weird stuff in just about every margin (apart from the text-only page), while Q13b just has nymphs in bath-type scenarios.

In short, Q13b does indeed look like a two-bifolio bath quire, while Q13a looks like a three-bifolio weird-stuff-with-pipes quire (not sure if I can quite get all the way to “medical” from where I currently am, but we’re motoring in the same kind of direction). So, good call, very well done! 🙂

As far as the page order goes, Q13b seems locked down, so we can put that to one side for now. For Q13a, f76r looks to me like the first page as well (as it would), so I’m very cool with that: but what of the final two bifolios?

You suggest that f76v faced f80r because of the top-right man apparently throwing stuff over to the people at the top of f80r, and that that would place f76v, f80r, f80v (three similar “medical” pages) in order in a block. Conversely, I suggested that f76v faced f77r because of the wiggly lines in both drawings (Curse p.64); because that would make the “rainbows” on f82v face the similarly arched pipe on f83r; and because they are currently adjacent (though that’s by far the weakest of the three reasons, admittedly).

But actually, I’m pretty comfortable with both orderings, because I suspect we’re pretty much bumped right up against the limits of what it is possible to infer from these drawings (in the absence of further evidence). All the same, splitting Q13 into /a and /b does make it very easy to narrow down what to go looking for in the codicology (basically, contact transfer from the very earliest layers of ink and paint) that might support or refute these basic ideas.

Incidentally, looking at f83v as the back page of Q13a does make me wonder whether this was quire X of the manuscript, as the big (and rather incongruous) drawing 1/4 of the way down does happen to have a giant ‘X’ visually embedded in its design. Just a thought! 🙂

I sort of anticipated your comment that you can’t tell medical from anything else at this point, I know I didn’t bring you up to speed on how and why I’m making such distinctions. It’s really a rather lengthy presentation of evidentiary procedure, something I’m having to write up in bits and pieces because I hate concentrating on it too long. Basically it started with looking at drawings such as the “four seasons”, or the “four winds” drawing on f86v3, and realizing that there is an underlying methodology of symbolism to the drawings that opens doors to the other drawings. For instance, if I were to ask a modern to draw a cloud, we’d probably all now draw a cloud similarly, since we all know the standard representation. But this guy didn’t have many standard guidelines that I can find. The four winds were commonly depicted as bellows, and the basic bellows structure is evident here as well, but the bellows are also drawn as cloud-like structures. The winds are evident and can be discerned, with the warm southern wind, the icy northern wind, and the eastern and western winds that bring snow and rain. So we can then determine what a cloud looks like in this guy’s mind, and what a bellows or strong gust/influence looks like. We know what ice looks like, we know what rain looks like.

The next part, and the lengthy part, was going back to Galenic books and matching the symbolism in the writings to the symbolism of the drawings. It’s just one of those things that when you start to nail one thing down, another and another follows, until you can finally understand the imagery to some degree. I never had much use for art appreciation classes, and I don’t think they were meant to do this kind of forensic discovery, but I think this is along those lines.

The three “medical” pages I’m keeping together all have medical instrumentation and treatments depicted in the drawings, with the same color scheme and sometimes multiple examples of the same device, so these clearly stay together as one single line of thinking. There’s the fumary treatment and syringe (douche bladder) on 76v, on 80r the suppository tool, the tweezers, the herb balls (or pessaries), and that ring thing I’ve been asking about, which I’m doing research on right now and think may also be an early vaginal pessary. The last purely medical page, 80v, has the syringe, the ring and at least two examples of aromatic baths. This page also has a drawing of some kind of hair or scalp treatment. These three pages are very heavily medical in their imagery, and since they are all on the same topic of treatments, they should be together.

The biologicals aren’t really about human biology, they represent the Galenic medicine view of the influences of humors on the internal organs. The artist depicts humors differently from astral influences, and astral influences differently from meteorological influences. Smoke is drawn differently from a cloud, and astrological bellows (forces) are drawn differently from wind bellows. This works not just for one drawing but across the spectrum of drawings, which I really like. If I were to write about this on the list it would go unheeded, but only in understanding the nature of the representations made by the author can one understand what he’s drawing, and once that level of understanding is reached, this all starts to have parallels in other medical writings, when no other approach finds enough parallels to be credible. But then again, had I actually started out with some degree in medieval codicology or something like Panovsky had, it wouldn’t have taken nearly this long to reach conclusions he’d already reached through brief examination, eh? 🙂

As another aside, looking at f84r and f75v as the outer two pages of Q13b, I don’t really get any kind of outer-side-of-the-quire feel from them. So I strongly suspect that there was once an additional outer bifolio to this (otherwise very small) quire which has got lost along the way.

Yes, it does seem to be incomplete.

Additionally, seeing Q13 as having been formed by merging two smaller quires would perhaps help explain another odd thing. If the two pharma wide bifolios (Q15’s f88-f89 and Q19’s f100-f101) originally sat side-by-side (100-101-88-89, as per the apparent progression of the jars), then that would be another example of two small quires sitting adjacent to each other, but having subsequently been turned into conventional nested quires in order to be bound.

My suspicion there is that the absence of original quire numbers on Q19 and Q20 could simply be because (a) as the final quire, Q20 was never actually numbered, and (b) when the quire numbers were first added, there might well not have been a Q19 at all – the bifolios in Q19 might well have been bound up inside other quires completely.

I think the next section I need to re-examine for my notes is the pharmaceutical section. I too have some unanswered questions about this section.

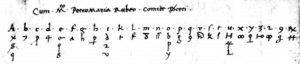

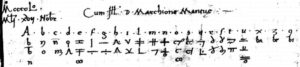

If you look at all the different handwritings used for the quire numbers (Curse p.17 is quite handy for this), do you get any kind of feeling that bifolios were on the move both before, during, and after the quire numbers were added?

Ah yes, well it just so happens that I’ve had your book handy just for such discussions. See, I’m not entirely ignoring you! 🙂

Basic differences of opinion, Q5 comes out in Jon Grove’s filter has having the same black ink component as that of Q6, when what you call Quire Hand 1 has no black ink component. Q19 and Q20 are definitely afterthoughts of someone, but because of ink and hand differences, we are in agreement that the quire marks are not all in the same hand. Some are probably added by binders in the same style, and I think I can probably match up the quire marks of this nature with the ink and hand of the particular binder. As we’ve seen with Q8 though, the quire marks (at least some of them) existed before the foliation, so this makes me think that the basic order was established before the two major binding sessions. I *think* (suspect without evidence) that the first three quire marks may be from the author himself, placed there in the first three herbal quires before the herbal-b’s were added, and no other quire marks are his, they were added by binders because the first three quires had quire marks, and the addition would have added a look of consistency to the bound book. I’ve always been of the opinion that if it was bound at all while in possession of the author, this would have been one of those loose bindings so common to workbooks, and nothing at all permanent. Just a thought. Speaking of quire marks, what scenario did you come up with to explain Q5 extended to Q3? It’s probably in your books somewhere, but please refresh my memory.

I think you understand what lies beneath that drives my quest for knowledge, I think you share this. I get so frustrated with people who say “we can’t know”, and usually invoke this phrase in defense of their own positions. I don’t think we can know everything, even after the book is read, since I think we both know there are substantial missing parts that will never be discovered. I think however that careful, educated examination and a rational approach can yield enough information that what we don’t know will be little.