As should be clear from the last few posts here, my Voynich research focus has recently turned to the wave of astronomical instruments that appeared in the German-speaking lands in the first half of the fifteenth century.

The person behind much of this wave would appear to be John of Gmunden (AKA Johannes von Gmunden, Johannes de Gamundia, etc) (c.1380 – 1442), but I’ll return to him in more detail in a separate post.

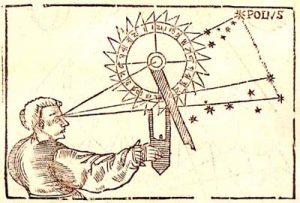

Even though I’ve been looking mostly at theorice planetarum of late, I’m also interested in the nocturlabe / nocturnal / sternuhr (‘star clock’), which similarly appeared in the 15th century. Even though the earliest known description of the astronomical mechanism behind this was written by Raymond Llull, the first actual nocturnals started to be built in the fifteenth century.

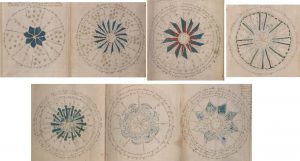

Hence I’ve long wondered whether the curiously-repetitive circular diagram on the Voynich Manuscript’s page f57v might actually be describing a nocturnal in some way. Yet the practical problem with pursuing this further was that I was lacking a good reference for the very early (fifteenth century) history of the nocturlabe.

Ernst Zinner’s Sternuhr History

This was exactly the point where Ernst Zinner’s (1956) Deutsche und niederländische astronomische Instrumente des 11.-18. Jahrhunderts landed heavily on my doorstep. (Though I bought it second-hand, it was actually from the Adler Planetarium, which was a nice coincidence).

Zinner outlines the history of the Sternuhr on pp. 164-166, but given that our focus here is the fifteenth century, I’ll only transcribe (and lightly HTMLize) p.164.

You’ll need to know that Zinner refers to manuscripts and objects by their index number in Zinner (1925) “Verzeichnis der astronomischen Handschriften des deutschen Kulturgebietes“: astronomy historians typically call these ‘Zinner numbers’ (e.g. “Zi 3593”).

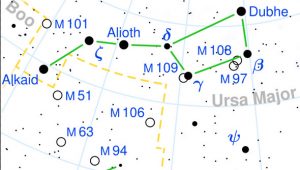

Oh, and you’ll also need to know the names of the stars in Ursa Major (despite having an Astronomy O-Level, I only knew Dubhe):

- α – Dubhe

- β – Merak

- γ – Phecda

- δ – Megraz

- ε – Alioth

- ζ – Mizar

- η – Alkaid = Benetnasch = Benenaz = the star right on the end of the plough handle

Finally: Dubhe and Merak were known as the ‘runners’ (Cursores) or ‘brothers’ (Fratres), that point towards Polaris, the Pole Star.

First paragraph…

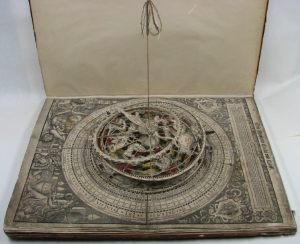

Die Sternuhr, auch Nachtuhr = horologium noctis = noctilabium = nocturnalis gennant, wurde in Frankreich erfunden [149 d S.8] und von Raimondo Lullo in seiner Arte de navegar 1295 beschreiben [Opera omnia, Mainz 1721]. Er verwendete den Polstern und die Fratres genannten Sterne des Großen Bären. Das Gerät wurder im Kreise des Schülers Johanns von Gmunden in Wien verwendet; denn die 1438 beendete Abschrift von Gmundens Arbeit über das Astrolab [253 Nr. 3593] enthält einen Hinweis auf die Sternuhr mit der Verwendung von Polaris und Dubhe. Die Sternuhr besteht aus einer runden Scheibe mit einem Loch in der Mitte, um das sich einige Scheiben und ein über die Scheibe hinausreichender Zeiger bewegen lassen. Durch das Loch wird der Polstern beobachtet und der Zieger auf die beiden Hinterräder des Großen Bären, bezeichnet als die Läufer (cursores) oder Brüder (fratres), oder auf den letzten Deichselstern Benenaz des Großen Bären oder auf andere helle Sterne eingestellt. Wenn das Datum bekannt ist, so läßt sich dann die gleichlange Stunde bestimmen. Um die Stunden in der Nacht abzählen zu können, wurden an der Stundenscheibe Zacken oder Zähne oder Knöpfe der Stunden angebracht. Die Sternuhr wurde gelegentlich auf der Rückseite eines Sonnenquadranten oder einer Sonnenuhr angebracht. Bereits die 1445 bis 1450 auszugsweise abgeschriebene Arbeit [253 Nr. 7464a] zeigt, daß die Sternuhr auf ihrer Rückseite einen Sonnenquadranten für 51° Polhöhe hatte, ebenso 253 Nr 7464 d, e von 1458 und 1512, Nr 7470 b von 1512, Nr. 7465 a von 1492 und 7464, wo das ganzDie Sternuhr, auch Nachtuhr = horologium noctis = noctilabium = nocturnalis gennant, wurde in Frankreich erfunden [149 d S.8] und von Raimondo Lullo in seiner Arte de navegar 1295 beschreiben [Opera omnia, Mainz 1721]. Er verwendete den Polstern und die Fratres genannten Sterne des Großen Bären. Das Gerät wurder im Kreise des Schülers Johanns von Gmunden in Wien verwendet; denn die 1438 beendete Abschrift von Gmundens Arbeit über das Astrolab [253 Nr. 3593] enthält einen Hinweis auf die Sternuhr mit der Verwendung von Polaris und Dubhe. Die Sternuhr besteht aus einer runden Scheibe mit einem Loch in der Mitte, um das sich einige Scheiben und ein über die Scheibe hinausreichender Zeiger bewegen lassen. Durch das Loch wird der Polstern beobachtet und der Zieger auf die beiden Hinterräder des Großen Bären, bezeichnet als die Läufer (cursores) oder Brüder (fratres), oder auf den letzten Deichselstern Benenaz des Großen Bären oder auf andere helle Sterne eingestellt. Wenn das Datum bekannt ist, so läßt sich dann die gleichlange Stunde bestimmen. Um die Stunden in der Nacht abzählen zu können, wurden an der Stundenscheibe Zacken oder Zähne oder Knöpfe der Stunden angebracht. Die Sternuhr wurde gelegentlich auf der Rückseite eines Sonnenquadranten oder einer Sonnenuhr angebracht. Bereits die 1445 bis 1450 auszugsweise abgeschriebene Arbeit [253 Nr. 7464a] zeigt, daß die Sternuhr auf ihrer Rückseite einen Sonnenquadranten für 51° Polhöhe hatte, ebenso 253 Nr 7464 d, e von 1458 und 1512, Nr 7470 b von 1512, Nr. 7465 a von 1492 und 7464, wo das ganze Instrument « spera » genannt ist wie in 7464 a.e Instrument « spera » genannt ist wie in 7464 a.

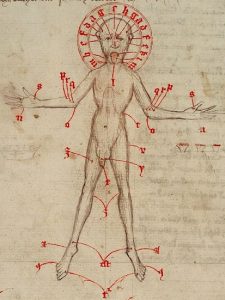

The star clock (also called night clock = horologium noctis = noctilabium = nocturnalis) was invented in France [Henri Michel. Du Prisme méridien au Siun-ki (Ciel et Terre 1950 S. 1-13) p.8] and described by Raymond Llull in his (1295) Arte de navegar [Opera omnia, Mainz 1721]. Llull used the ‘Fratres’ pair of stars in the Ursa Major constellation. The device was used in the circle of the student Johannes von Gmunden in Vienna; a 1438 copy of Gmunden’s work on the Astrolabe [Zi 3593] describes a star clock using Polaris and Dubhe. The star clock consists of a round disc with a hole in the middle around which both a number of discs and a pointer extending beyond [the edge of] the disc can be rotated. Through the [central] hole, the [Pole Star] is observed and the pointer is then set to the two rear stars of Ursa Major [known as the runners (‘Cursores’) or brothers (‘Fratres’)], or to Benenaz [Eta Ursae Majoris, the ‘plough handle’ star of the Ursa Major constellation] or other bright stars. If the date is known, this device helps determine the hour of the night. To read the hour off in the dark, teeth or buttons (one for each hour) were attached to the hour disc. Star clocks were occasionally attached to the backs of quadrants or sundials. Already in 1445 to 1450 the partially copied work Zi 7464a demonstrates that the star clock on its back had a sun quadrant set for 51° latitude, likewise:

- Zi 7464d [1458]

- Zi 7464e [1512]

- Zi 7470b [1512]

- Zi 7465a [1492] and

- Zi 7464, where the whole instrument is called a «spera», as in Zi 7464a.

Second paragraph…

Zuerst wurde Dubhe (α Ursa) als der Richtstern des Zeigers genannt. Dieser Stern oder die beiden äußeren Rädersterne werden angegeben auch in den Arbeiten 253 Nr. 7468 b, geschrieben nach 1452, 253 Nr. 7468 nach 1457, 253 Nr. 7467 von 1459, 253 Nr. 7464 von 1461, 253 Nr. 7468 c um 1466, 253 Nr. 7463 a nach 1475. In 253 Nr. 7468 b ist als Leitstern außer Dubhe auch Benenaz genannt und dazu die Örter von Polaris, Dubhe und Benenaz für 1438 angegeben. Benenaz wird auch genannt in Wilhelms Arbeit [253 Nr. 11716] über die Herstellung und Verwendung der Sternuhr um 1471. Da Wilhelm Schüler Peurbachs war, so gehört auch seine Arbeit zu den Wiener Arbeiten.

Dubhe (α Ursa) was the first star to be mentioned in connection with the nocturnal’s pointer. This star or the two outermost stars of Ursa Major are also given in:

- Zi 7468b [after 1452]

- Zi 7468 [after 1457]

- Zi 7467 [from 1459]

- Zi 7464 [from 1461]

- Zi 7468c [1466]

- Zi 7463a [after 1475].

In Zi 7468b, Benenaz is also mentioned as the guiding star in addition to Dubhe and the locations of Polaris, Dubhe and Benenaz for 1438 are given. Benenaz is also mentioned in Wilhelm’s work Zi 11716 [around 1471] on the construction and use of the star clock. Since Wilhelm was a student of Peurbach, his work also belongs to the Viennese circle.

Third paragraph…

In der um 1460 entstandenen Arbeit [253 Nr. 7472] warden die Sterne β (Kochab) und γ des Kleinen Bären und zwar mit ihrem Ort für 1460 angegeben. Nun bilden diese Sterne mit Polaris nicht eine gerade Linie, so daß ein Irrtum vorliegen dürfte. Vielleicht war Kochab, der später auch von Köbel erwähnt wurde, allein gemeint.

In Zi 7472 [written around 1460], the stars β (Kochab) and γ of Ursa Minor are given, with their location for 1460. However these two stars do not form a straight line with Polaris, so there may be an error. Perhaps Kochab, which was later mentioned by Köbel, was meant to be used on its own.

Fourth paragraph…

Die Sternuhr wird so verwendet, daß zuerst die gezackte Stundenscheibe mit 12 Uhr auf den Monatstag gelegt wird ; dann gibt der auf die Hinterräder eingestellte Zeiger die Stunde an (Tafel 57, 1).

To use the star clock, once the jagged hour disc is placed on the day of the month at 12 o’clock, the pointer set on the rear wheels should indicate the hour (plate 57, 1).

Guards, Guards!

This is all very interesting, and helps to give an overall timeline. The ‘guards’ I mentioned previously (that point to Polaris) are another name for the same cursores / fratres first mentioned by Llull. I also didn’t know that Dubhe is the official star of the State of Utah. 🙂

The next step here will be to look more closely at the specific early 15th century manuscripts listed by Zinner, to see how they fit together into the overall nocturlabe timeline.