I mentioned in a comment on Koen G’s recent post that I thought that Voynichese benched gallows (i.e. gallows that have a ch glyph struck through them) may well be nothing more complex than a different way of writing gallows+ch; and that I thought this was much more likely than the alternative notion that it was a different way of writing ch+gallows.

When Koen asked me what evidence I had for this, I thought that I ought to write a brief post explaining how I got there (i.e. rather than cramming my “truly marvelous demonstration” into a Fermatian margin). So here goes.

Yes, It’s Contact Tables (Again)

The evidence I’d point to is from (you guessed it) contact tables for glyphs following benched gallows. The notable feature of these I mentioned recently on Cipher Mysteries (though the obeservation is, of course, as old as the hills) is that benched gallows are only very rarely followed by -ch.

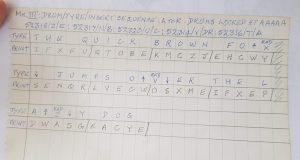

Here’s a simple parsed count example (Takahashi transcription), showing how very rare benched gallows + -ch are as compared to both -e and -ee:

| cth 712 | cthe 167 | cthee 23 | cthch 3 |

| ckh 629 | ckhe 222 | ckhee 20 | ckhch 5 |

| cph 147 | cphe 56 | cphee 8 | cphch 1 |

| cfh 59 | cfhe 13 | cfhee 1 | cfhch 0 |

Baseline: (ch 10652), of which (che 4138), (chee 742), and (chch 18)

Furthermore, as I noted in that post, almost all of the places where benched gallows are followed by ch seem to be Takahashi’s transcription errors (sorry Takahashi-san).

Compare and contrast with the contact tables for the preceding glyph, where the ch- instance counts hugely outnumber the counts for e- and ee-:

| cth 701 | ecth 59 | eecth 6 | chcth 139 |

| ckh 501 | eckh 124 | eeckh 9 | chckh 242 |

| cph 177 | ecph 7 | eecph 1 | chcph 27 |

| cfh 54 | ecfh 3 | eecfh 1 | chcfh 15 |

Baseline: (ch 10652), of which (ech 143), (eech 33), and (chch 18)

As a sidenote, the interesting things in this particular table are (a) how rarely benched gallows are preceded by ee- (far less than by just e- or ch-), and (b) how frequently benched gallows are preceded by ch- when ch itself is very rarely preceded by ch-.

So, What’s Going On Here?

I think it’s safe to say that there is probably a really basic reason why benched gallows preceded by ch- are found so much more often than benched gallows followed by -ch. But what might that reason be?

For me, the suspicion is simply that c+gallows+h is just a different way of writing gallows+ch. The contact tables I quote above certainly don’t seem to offer anything to support the alternative scenario where c+gallows+h is a different way of writing ch+gallows.

To my eyes, replacing benched gallows with gallows+ch would match the statistics baseline for che/chee/chch far more closely than replacing benched gallows with ch+gallows would match the statistics baseline for ech/eech/chch. That is, the benched gallows right contact tables (i.e. the contacts that benched gallows have with glyphs immediately following them to the right) seem to me to broadly match the ch right contact tables, but the benched gallows left contact tables don’t obviously match the ch left contact tables.

The big issue here – as always, though – is one of proof. It’s all very well my speculating that it would be better to replace benched gallows with gallows+ch rather than ch+gallows, but how can this be made stronger?

Though I’m not sure that it would be possible to turn this gallows+ch replacement hypothesis into a smoking-gun proof, I do suspect that it could be tested much more rigorously. Perhaps CM readers will have good suggestions about how to carry out a suitable test (or three). 🙂

Finally: Might ch Be Enciphering U?

To me, Voynichese’s various families of shapes and glyph behaviours look (much as John Tiltman suggested) like a grab-bag of contemporary cipher tricks. As a result, it would make a lot of sense to me if the distinctive benched gallows was simply one of the set of slightly older cipher tricks that were artfully combined to form Voynichese.

Along these lines, I’ve previously floated the idea (based mainly on the look of the benched gallows, but also on my long-held suspicion that e/ee/ch/sh might somehow be vowels) that Voynichese ch might in fact encipher plaintext U/V. This is because I can easily imagine that c+gallows+h may have begun its life as an early 15th century steganographic trick used to disguise or visually disrupt QU patterns before being absorbed into the Voynichese Borg mind.

Replacing benched gallows with gallows+ch would be entirely consistent with this idea (though note that the gallows need not necessarily be enciphering Q, even if the trick started that way), so it’s possible that both ideas might turn out to be true simultaneously.

Incidentally: in “The Curse of the Voynich” (p.177), I mentioned a strikethrough trick that appeared in an “otherwise unremarkable” 1455 cipher (Ludovico Petronio Senen) to encipher the Tironian-style ‘subscriptio’ shorthand sign (e.g. that turns “p” into “p[er]”). My speculation here is therefore that the strikethrough trick may have first emerged in this general era, though instead used to visually disguise plaintext U’s.

Hence one thing I have been meaning to do recently is to trawl carefully through Mark Knowles’ fascinating haul of 1400–1450 Northern Italian ciphers to see if there is any indication there that a strikethrough trick was ever used in one of those ciphers to disguise the U in QU pairs. You might have thought that encipherers would have added a special token for “QU”, or might have simply chosen to omit the U after Q: but neither of these options typically seems to have happened in this general timeframe (outside of the most complicated syllabic ciphers).