Today’s Cipher Mysteries post comes from long-time Voynich researcher Jan Hurych, who very kindly agreed to go through Otakar Zachar’s (1899) monograph on the “Cesta spravedliva v alchymii” (“The True Path of Alchemy”) manuscript by Antonio of Florence dated 1457. Here’s what Jan found…

* * * * * * *

While Otakar Zachar’s name is now generally unknown, he appears to have been connected with various Czech National Museum archivists who he mentions in his book, and so was probably a known historical scholar.

His book is basically a commentary on (and a modern Czech translation of) the manuscript “Cesta spravedliva v alchymii” dated 1457, and which was written in the old Czech medieval language. Though its title translates as “The Right [or righteous, or just, or correct] Way in Alchemy” , it is not about travel 🙂 but rather about the alchemical methods and recipes written therein.

Zachar claims he saw the Czech original (or rather a copy, as explained below) in the National Museum (and which should today be in the National Library): however, becasue I was not able to reach that, I will describe only what is in his book, namely in his conclusion (from p.95 onwards). He also quotes some Latin text taken from Knihovna Národního muzea v Praze MS III H 11 (starting at its page 129r) that relates to this same manuscript, but which dates from around after 1606.

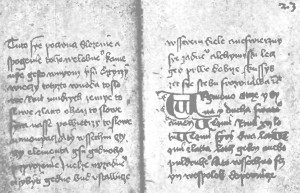

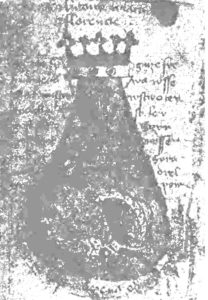

Zachar claims that the book was written by the Czech servant of an Italian alchemist called Antonio di Firenze (Florence) and was then hidden somewhere (in Bohemia?). In 1606 (an interesting date!) it was discovered – a hearsay, Zachar admits – by a doctor of medicine (perhaps Czech?) who recognized its value and brought the book to Jerusalem (apparently personally). After the doctor’s death, the book was hidden again (where, in Jerusalem? Or back in Bohemia?) and then rediscovered. Zachar studied the manuscript for several months and copied its text verbatim for his own book (the original text was written on parchment in black ink, with only its chapter headings in red).

The manuscript describes four methods for making gold:-

- A bottle of elixir provides gold in value of 30 marks

- A cheaper method, providing only gold “fluviatile”, that cannot stand fire

- An improvement on method #1

- Since gold above (the result of all three methods) contains sulphur, this method is a new way by which the “Veneris” [note that “Venus” is normally the alchemical codeword for “copper”] can be removed

Zachar thinks that #4 is the real secret, and that Antonio and other Italians in Bohemia were looking for a special kind of sulphur, say a “secret sulphur” as it was called in old Czech. Zachar wonders where in Bohemia they were looking… Incidentally, here he calls Antonio “Venezian” (benatcan) so was he from Venice and not from Florence as Zachar said at the beginning? Apparently this was only Zachar’s slight mistake. He also mentioned that “Czech ways” were not as advanced as Italian ones. He noted that some passages in the manuscript were erazed – these passages interested Zachar most, but the erasure was too good for him to read past – he apparently did not have Wilfrid Voynich’s dark room! 🙂

Zachar believes that the Czech manuscript is only a copy of some original – why, he does not say. Also, nothing more is known about Antonio’s servant (who wrote down this manuscript). As for “1457”, that could well be when the original was written, the copy could have been much younger [my comment, j.h.].

So the book – or its history only? – must have been known in the 17th century while the good doctor was still alive, since the book was then in Jerusalem and hidden again after his death. Of course, all this could have been merely the history of the original manuscript, while what Hanka found in Bohemia was a copy (though exactly when he did was never noted) which may never have travelled to Jerusalem and back again. 🙂

All in all, Zachar’s book does not describe the Voynich Manuscript, but another book entirely. Whether Antonio himself ever wrote any book, especially the one we now call the VMs – we cannot tell. The Czech manuscript is of course solely concerned with alchemy – no zodiacs, no stars, and no bathing beauties!

* * * * * *

To make things even more complicated, Zachar claims the book reached the National museum via Mr. Vaclav Hanka, who was (in)famous for the discovery of two historical Czech manuscripts (Zelenohorsky, disc. 1817 and Kralodvorsky, 1818). Both of them are today generally considered as fakes, written from nationalistic motives – even though Hanka was an expert on Medieval Czech langauge, he apparently made a number of linguistic mistakes there. 🙂 Zachar confirms he saw the manuscript being first mentioned in 1825 (Jungman’s book History of Czech Literature) but he also quotes some of the above history, from the copies of some alchemical works dating from the 1600’s. He unfortunately omits to say how he found out (or worked out) that they described exactly the same manuscript. 😮

Hanka himself lived from 1791 till 1861 and from 1819 onwards he was an archivist in a Czech museum. After his discovery of those two manuscripts, they became the subject of the largely popularized nationalistic “Battle Of The Manuscripts” which lasted right up until the end of the 20th century. The quarrel split the Czech nation (which back then was under the control of the Austrian Empire) into two groups: passionate defenders and passionate rejectors. The battle later subsided and while it never fully stopped, today most people think both manuscripts were just frauds. That is not to say the old “Cesta spravedliva” definitely comes from the workshop of Hanka (and his friend Linda), but the almost-perfect medieval Czech language might just be a gentle giveway…