[Here’s a guest posting from my friend, the well-known Voynich contrarian Glen Claston. Though he originally intended it as a comment to my recent post on Voynich Manuscript Quire 8 [Q8], it actually deserved a whole post to itself. I’ve lightly edited it to house style, and added a couple of pictures.]

Nick asked me to look at the blog, and though I don’t plan to be a regular poster, he’s going on about things that matter a great deal, so we need to examine them very carefully.

The [“ij”] mark at the bottom of f57v is in line with two other erased marks on folios, as well as erased symbols in Q1 and Q2 that Nick and I discussed some time ago. The original author apparently used a symbol system instead of a standard system, and much of his work has been removed. Quirization and foliation are not the work of the original author. I plan to publish this in a book entitled “The Curse of the Curse of the Voynich”. 🙂

Voynich Manuscript f42r folio number

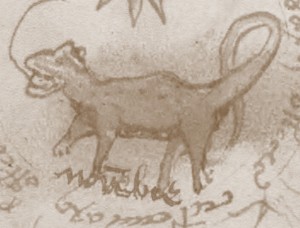

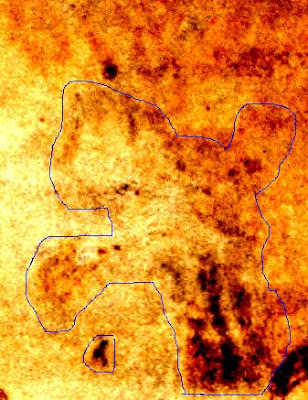

Rene Zandbergen also brings up an interesting observation about f42r, that the crystals appear to be on top of the foliation. Yes, I’m certain that is the case, but I don’t reach the same conclusion that Rene does in this regard. In the image above, the foliation clearly overlaps the drawing lines and the color pigment, but at the same time, this entire region is a section exposed to water damage, which might explain Rene’s observation of the crystals overlapping the burned-in ink. IF the pigment includes mineral salts as many commonly do, this would explain Rene’s observations, as they would have re-crystalized over the existing material. It would require a rather closer inspection to see if this is the case.

If Rene’s observation holds, there is indeed something seriously wrong with the Voynich, since foliation before coloration has a very dramatic implication on known VMs construction, and I for one would have to throw out years of research and start anew, as would many. I recall that I had issues with Rene before on “retouching” because these darker patches fell into areas that were also affected by moisture. As it happens, I do apologize much belatedly to Rene for suggesting that just because some of these didn’t match, his identification of retouching in the astrological section was wrong, when it proved to be spot-on. It was my fault for generalizing, and to say that we all make mistakes is not a good enough excuse, I owe it to myself and to the VMs to be as precise as possible.

[Nick: as far as the paints go, I think the consensus now is more that different paints were added at different times, though I suspect the “light painter” / “heavy painter” binary division may well prove to be far too simplistic – because of the large number of paints present, I can quite conceive that these might have been added by four or five later “heavy painters”.]

As far as the rosettes section [Q14] goes, Nick is suggesting here that Q14 belongs to Q8, and though I wouldn’t exactly state that in the way Nick has suggested, I entirely agree. The rosettes is a part of the astronomical discussion, so it’s not in its right place. A large folio can get ripped out rather easily, and be placed back in the book in random order. It’s an hypothesis, but is it testable?

It turns out that the rosettes contains a record that helps us place some items in order. There are tears in the unused fold of the rosettes, damage beyond what normal foldouts have seen, and these tears hold information. The quire mark only works if the rosettes was bound in this torn seam, and the foliation only works if the binding of this foldout is in its current place. That says that the maker of the quire marks was not the maker of the original foliation, that the foliation was a product of at least one successive binding. There are two distinguishable hands in the foliation, two successive bindings after the quire mark binder. Two inks that I can identify in the foliation bindings, and places where quire marks were added that weren’t there originally.

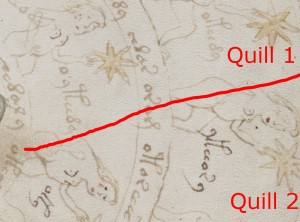

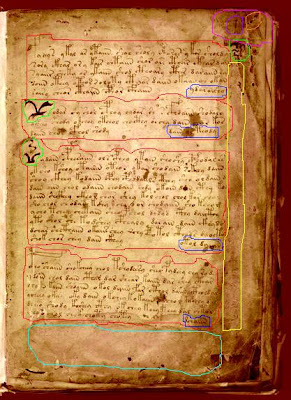

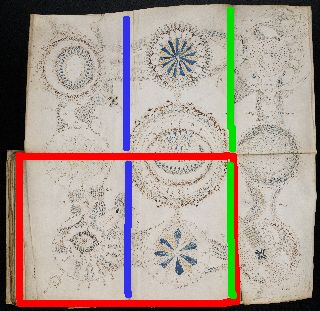

[Nick: GC is proposing that the nine rosettes fold-out f86 was originally attached to the rest of the manuscript along the (now badly damaged) crease highlighted green (above), rather than along the crease highlighted blue. The shape of the whole codex is highlighted in red.]

It’s a complicated picture that needs a degree of clarification, but there is no way around the idea that the manuscript went through at least three bindings. The big question is – does any of these bindings reflect the original order of construction? The answer is a resounding NO.

Again I go to the rosettes for history, and I need only look on the back of the rosettes to see that the discussion includes the four seasons and the four winds. All my research into parallel texts says that this is the meterological part of the astronomical discussion, and belongs firmly in the astronomical section. This also says that the rosettes on the reverse is a meteorological mappa mundi, and read in that venue of comprehension it’s imagery becomes meaningful and schematic to other VMs imagery. It helps that one page in the first astronomical section [in Quire 8] exhibits similar damage to that of the original rosettes page, and Nick is right that the pages in this section appear to be inverted.

I’ve been through the whole range of arguments over the years, and I weary of argument that doesn’t move me forward, but this is a discussion that needs to be moved forward on several fronts, and I will follow this discussion with interest.

What I am seeing is that the quire numbers were placed on probably the first binding, but I’ve always been of the opinion that the manuscript existed unbound during much of the author’s life. I now have much more information to back up that idea, and as you know, I was once of the opinion that it was the author that first quirized, which is something I can now disprove in abundance. Order changes and shuffling I can’t comment on, but there is evidence that the author himself made some major changes, and these changes were substantially reflected on the first binding but the manuscript was not in a permanently bound condition when the author left off/died.

Rene for one would understand that in making these decisions, I’m weighing intelligent choice against mishap, and using a set of parallel texts on these subjects to determine which is which. One doesn’t even require these options in viewing the interlacing of herbal-a and herbal-b herbals. One does however, need to know why the herbal-a herbal pages were separated from the herbal-a pharmaceuticals and additional information stuffed in between, much of this in a different script. Herbal-a herbals are congruent with herbal-a herbals in the pharmaceutical section, the latter sometimes drawn on the same bifolio/foldouts as the pharmaceuticals, and as Nick and I discussed recently, there is physical contact information that ties them together in a time-line of construction. These are connected in multiple ways to the same time line, and the intervening information is connected to a separate time line, and the construction is a progressive construction, so could this have been the act of binder and not the author? Could this intelligent construction occur passively, and not actively? There’s an argument in there somewhere.

Grant for a moment that I don’t think the book was bound during the author’s life, and I am certain it was not bound before the drawings/text/ paints were added (it’s damned hard to draw, paint, and write all the way into bound gutters on so many pages – common sense observation, eh?). What’s just as important is when quire marks ceased and foliation began. Dee used bifolio quire markings in his book of 1562, and though page numbering was becoming popular in printed documents by this time, Dee chose not to use it, choosing a manuscript format instead. It’s a generational thing, and I feel that the foliation is at least 17th century. The quirization has a problem with dating as Rene pointed out, that it could be someone older that didn’t use the modern format, or it could have been someone before the modern format became prominent. The rosettes’ gutter damage however, says that there was a good deal of time between the quire marks and the foliation, because they couldn’t possibly have happened at the same time, and the quire marks are apparently a good deal older than the foliation.

Make of this all what you will! — Glen Claston