Nick: here’s another full-on guest post from Glen Claston, with a little bit of friendly banter from me in blue…

The different ways some little detail can be viewed is so much of the fun we have with the VMS. Until supporting [or refuting] information can be found for either view, neither is more valid than the other; and indeed, we weigh the validity of one over the other based on common perception.

My view on the binding had to do with the placement of the quire mark, and as you see, I used a minimal amount of information to formulate an hypothetical scenario that may or may not be wrong. I didn’t do this to be contrary, I did it to explain some of the things I’m seeing, and of course this may not be the right explanation, or only portions of it may be correct. That’s sort of why it’s only an hypothesis.

What I need to do next is to search these pages for some evidence that either supports or refutes this hypothesis, and this is usually where one of my hypotheses falls out of my own favor and gets replaced with something else, something like Ernie’s common sense idea, which is the one I originally held until I had problems with the placement of both the foldout and the quire mark. The good thing about it is that there is usually more information to be gathered from the pages – as Nick said, a million fragmentary clues…..

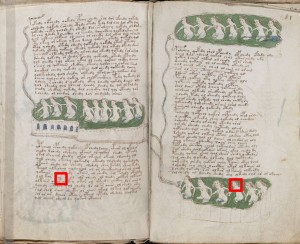

Nick: for example, I think we can still see some tiny original sewing holes along Glen’s secondary vertical fold on the nine-rosette page. Further, if you reorder Q8 with its astronomical pages at the back and insert the nine-rosette section, you rejoin the “magic circle” on f57v with the two other “magic circle”-like pages on the back of the nine-rosette sexfolio. And it may possibly be no coincidence that doing this happens to move the very similar marginalia / doodlings / signatures on f86v3 and f66v closer together.

But herein lies one of the major problems with this sort of research (and it’s only a problem to those who don’t recognize that everyone, including themselves, is prone to this type of thinking) – we tend to reason out large scenarios based on a minimal set of information, and when something doesn’t exactly agree with that scenario, we don’t modify it or throw it out. I am no different in that when necessary, I tend to modify before discarding, but I admit that in 23 years of research, I’ve discarded almost everything but the most basic concepts numerous times. It was only after the MrSids images were made available that I was able to revisit some old ideas and gain substantial ground in this endeavor… and even now, some things are still in the hypothetical stage. But when you change one leg of an hypothesis that stands on only two or three, the whole thing usually comes crashing down with a thunderous sound – I can hear that sound from clear across the ocean on occasion. 🙂

Nick: that’s strange, I get to hear that same noise too from time to time, also coming across the same ocean. 🙂

To me it’s rather easy to demonstrate through parallel texts that the rosettes page is firmly a part of the astronomical discussion, and should be placed before the celestial part of that discussion, and I have a good deal of professional opinion, (historical and contemporary) that agrees. The Astronomical discussion falls appropriately just before the astrological discussion and begins with the terrestrial portion of the astronomical discussion, so when the rosettes is placed back into its proper place, the terrestrial discussion precedes the celestial discussion and then transitions into astrology, as it should. The book then falls into an order that is in line with the order of presentation given in the parallel texts and commentaries. The book transitions from herbs to astronomical, and astronomical to astrological, on mixed bifolios, physical codicological information that establishes within reason that this particular order was chosen by the author him/herself. This is the higher level of argument, since this is part of a theory that encompasses the entire content and original purpose of the manuscript. That’s the general theory of relativity, but some other source of information is required to extract a specialized theory of relativity. This requires a gathering and interpretation of the physical codicological information, not as easy as it appears.

We’re faced with the obvious fact that some bifolios and foldouts in this book are currently bound out of order, and some students have gone so far as to suggest that it looks like the pages were dropped on the floor and recollated randomly.

Nick: to be precise, I’d say that a few bifolios did probably manage to cling together despite being dropped 🙂 , but for the greatest part I don’t see much retained structure in Quires 2 through 7, in Q13, Q15, Q19 and even Q20 (if Elmar is right), while Q8 seems back to front and Q9 and Q14 are misbound. And I’m not 100% convinced by Q1 either!

To me it’s not that drastic, most things are in their category, if not their proper order, but the question of original collation has so much bearing on so many aspects of this study that it needs to be addressed in a very serious manner, and by that I mean the gathering of codicological evidence that can be molded into a working hypothesis or theory regarding the original construction and collation of the book. Historical scenarios that are based on a great deal of codicological information have many legs to stand on, so they don’t topple simply because one ‘fact’ or observation changes or gets reinterpreted. Ergo, collect all the codicological information possible, and collect it in one place so it can be easily referenced when trying to formulate hypotheses. No, no one after D’Imperio has done that – Rene has tried on one level of the manuscript, but no one has collected all the physical observations into a single database. Is this a task too large to be accomplished? It’s done routinely in other scientific disciplines, why not here?

Nick: well… I did try to do precisely this in the ‘Jumbled Jigsaws’ chapter of “The Curse” to a far greater degree than D’Imperio was ever able to, but I would certainly agree that it would take 500 fairly specialized pages to begin to do the topic justice. 🙂

I give you an example of how much codicological evidence matters, and I’ll provide an example that only requires a slight modification in Nick’s hypothesis of multiple painters, an hypothesis I don’t accept on other evidence, but I’ll give an example that buys into his hypothesis nonetheless, just so I’m not viewed entirely as a “contrarian”. There are three fresh-paint transfer marks near the bottom of f87v that come from the upper middle portion of f16v. Don’t get all worked up at the distance between these pages, because we know (or at least I know) that the herbals and the pharmaceuticals were once connected. The point of discussion here is that these offset transfers could not have taken place if these pages were bound before this red paint was applied. Nick is able to modify his hypothesis to say that the binding was only at the quirization stage, and that these outside folios can lay on top of one another at this stage of binding when the paint transfer occurred. That’s correct, that’s one scenario, and Nick only has to remove one leg of his hypothesis in order to accommodate this information – instead of being entirely pre-bound, now it’s bound only in quires. That works for Nick, and frankly works for me until I find something that says it doesn’t.

But I draw something else from this that Nick doesn’t address, and that is that the same red pigment is present on the two pages, as well as on the foldout which contains f87r. That leads me to a one-legged hypothesis that the guy went through his pages and painted one color, then went through again to apply another color, as opposed to our modern view of an artist who would paint in various colors simultaneously. We’re not on different wavelengths in our thinking, Nick and I, we’re just liable to reach different conclusions based on the same information, and that because we filter the information differently. You see, I have another category of research which includes unfinished drawings and paintings, and I see this through a different filter than Nick sees it.

Nick: I have no huge problem with the idea of someone applying paints one at a time. It would be consistent with my view that (for example) the heavy blue painter mixed his/her blue paint suitable for painting on paper (rather than on vellum) and rushed through the (already finally-bound) manuscript daubing it wherever he/she saw fit… only realising later that it hadn’t dried quickly enough, leaving a mess all over the facing pages.

The answer to such a simple question as to when and how the paints were applied may be more complicated than either Nick or I presently presume, and no matter what, we will both be modifying our opinions when the information is finally gathered and tabulated. I assume at present that because so much of the painting falls into gutters, it was done unbound. Nick thinks it was done pre-bound. I see now that some specialized paints were an after-work, possibly quire-bound, possibly not, while the common watercolors had to have been applied in an unbound state. Neither of us are entirely right, neither of us are entirely wrong, and there is more to be learned before the final tally can be made. Choose this red pigment, is there at least one place where it could not have been applied after the manuscript was bound? I don’t know, I haven’t done that study yet, the question has only recently arisen. And what frakking bit of difference does this make anyway? ;-{

It’s that hypothesis with only two or three legs thing again, that’s where this makes a big difference. I get so irritated with the “multiple painter” thing I simply want to scream, simply because it introduces multiple and extraneous unproven human elements into an hitherto unresolved picture, without first following evidentiary procedure. This particular fresh-paint transfer is in the A-herbal range, simply another connection between the pharmaceutical section and the herbal section, something I’ve been quite clear about – these were once connected. Post-bound painting as Nick suggests means that I should find evidence that this red pigment was also applied to pages that are written in the B script, and applied at a time where the A’s and B’s were already bound together. Does that evidence exist? I’m good at lists of codicological evidence, we’ll see if it does or not. And does Nick’s ‘quirized binding’ approach hold water against other evidence? We’ll find out, and these things will be discovered through gathering and collating the codicological evidence available to us. It’s a wonderful thing, that we have at our fingertips the information to do this in scientific fashion.

I remember the reaction on the old list when Nick and I went to logger-heads over something as apparently meaningless as blue paint, and that for me was what separated Nick from the pack in many ways. It wasn’t the love of argument or the basic disagreement, but the fact that Nick was willing to study and research in support of his claim. He was not a simple defender of his stance, he was an active participant in the argument, and though we both still disagree on this one point, the amount of new codicological information and rational thought generated in the course of this simple argument has never been exceeded in the history of VMS research.

I hope that this gives Emily and others some idea of why the simplest of observations can have the most profound impact in this line of research, and I welcome anyone that wishes to add to our base of knowledge, no matter how small. Collaboration can be a great deal of fun, and it’s guaranteed to hone your perception skills. When you start you’re going to get shot down a lot, just like a video game, but as you progress your impact will be much greater, just like a video game. This is your chance to hone a set of skills you didn’t think you had.