Some further notes on our poor plucky pigeon with his red Bakelite cipher payload.

People have been leaving some very interesting comments here, presumably spurred into action by today’s BBC piece on the mysterious bird. Moshe Rubin and Keoghly independently pointed out that “27” is a check figure to confirm that the sheet should contain 27 blocks of encrypted letters (as indeed it does), and both say that this was “standard fare for crypto“; while Keoghly adds that “1525/6 is likely [a reference] to [the] one time pad/offset used“. Bob Yeldham also helpfully notes that “the 37 & 40 on the rings denotes the year the bird was ringed that’s assuming the correct year ring was used, ringing was usually done 7 days after hatching.” Thanks to all of you!

What is also nice is that plenty of people seem to have rushed off to buy copies of Leo Marks’ very enjoyable book “Between Silk & Cyanide”, one of the best code-related books ever written, I’d say (even if some people have since asserted that Marks may have been an unreliable witness). Read it with care, for sure, but definitely read it! 🙂

I also ought to add my own thoughts from the last few weeks… and perhaps there’s an answer of sorts hidden in there.

My first reaction (that it might be a poem code sent from Douai early in the war) didn’t really stand up to analysis – having played with this in an Excel spreadsheet, I don’t think any kind of pure transposition is going to jump out from it. Though it resembles a poem code, Leo Marks specifically describes SoE’s sending cryptograms later in the war (particularly towards D-Day) that resembled the earlier poem codes, mainly to mislead Axis codebreakers: but by then Marks had (so he said) managed to persuade The Powers That Be to use one-time pads which were, to all intents and purposes, uncrackable then – or now, for that matter.

Having said that, what interests me (as an historian) is what we can tell from the rest of the message. For example, we know that the same message was sent back to the UK on two different pigeons, both of whose owners were members of the National Union of Racing Pigeons – “NURP 40 TW 194” (our dead pigeon) and “NURP 37 DK 76”. Yet we still have no word from the Racing Pigeon magazine (who presumably have all manner of racing-pigeon-related archives) on who those owners were, or where they lived.

Yet I think we can make a sensible guess at what happened here!

The message was addressed to X02, which (I believe) was Bomber Command in High Wycombe, Bucks (of which my aunt was once Mayor, incidentally), so it’s likely that we’re looking for locations in South-East England not too far from there. Hence I’ve already noted that our pigeon’s “TW” owner id could well have meant “Twickenham”, while similarly “DK” could very easily have been “Denmark Hill”. And we also know that the pigeon ended up in the chimney of David Martin’s house in Bletchingley (near Redhill) on its way home.

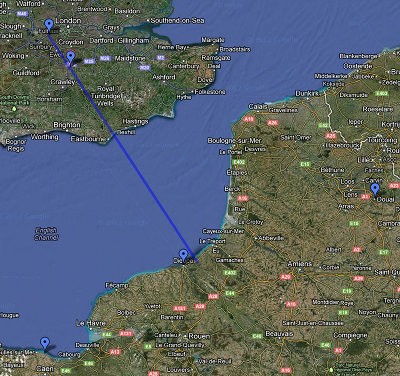

So let’s put it all into Google Maps and trace a possibly Twickenham-based pigeon backwards in time as the crow pigeon flies:-

If I’m right that “TW” is Twickenham (and it could just as easily be “Thomas Wilson”, I know, I know), then I think what we have here could be a pigeon flying back from Dieppe to Twickenham via Bletchingley. And one of the most [in]famous missions of WW2 was the Dieppe Raid of 19 August 1942, which went just about as badly as could be feared. So… could this have contained a desperate message sent back to Bomber Command to get help from the air on that dreadful occasion? Of all the possible scenarios discussed for our mystery pigeon’s journey, perhaps this is the one that has a (if you’ll forgive my pigeon-related pun) ring of truth!

Update: having said all that, if you follow the same line directly into the heart of France you hit Paris almost directly. Dieppe just happens to be the nearest point to Britain: all the same, until anyone knows any better, my pet name for this dead pigeon is going to be “Johnny Dieppe”, I hope nobody minds too much. 😉