A few days back, two small book-shaped things arrived in the post: and I’ve been pondering what to say about them ever since. In fact, I’ve been struggling to work out what I think about them… you’ll see what I mean in a moment.

You might superficially compare them with, for example, Luigi Serafini’s famously unreadable book: however, I have relatively little doubt that, beneath all its overevolved, madly-mutated faux-alien language tropes, Codex Seraphinianus does actually express some kind of coherent linguistic knot that might ultimately be untied, whereas Michael Jacobson’s “asemic” books claim to be actively meaningless. That is, while they play with the form of narrative and abstract expressive shape, they don’t actually say anything – any kind of meaning you take away from them is your problem (or, conversely, your gift).

Perhaps the right way to classify them, then, is as some kind of visual anti-poetry, a kind of Dada take on the postmodernist anti-meaning turn. Which is to say: if all texts are ultimately meaningless in themselves (and only incidentally form meaning in the reader’s mind), then why are you surprised that these books are too?

Alternatively, perhaps there is actually a hidden higher-level message, so that if you turn the pages upside down and squint your eyes in just the right way, what emerges is something along the lines of “The Magic Words are Squeamish Ossifrage“, etc. So, a good part of the fun is working out whether there’s a joke (and if there is, whether it’s on you).

Whatever your particular take happens to be, I think you can still enjoy them purely on their own visual merits: for all their (claimed) lack of meaning, Michael’s two books do jump with a refreshingly jazz-like joy:-

- Action Figures (which seems to have started life in an exercise book) is, I would say, the weaker of the pair: I get the impression of an early youth (mis)spent with a spray can, trying as a young man to give expression to the same basic urges, but channelling them within structural rules (such as minimizing shape repetition, consistency of line, etc). Neat, but Mayan street-whimsical rather than obviously challenging.

- The Giant’s Fence is, by comparison, a far more sophisticated objet d’art, even if it is apparently influenced by Max Ernst’s Maximiliana. Here, Jacobson seems to have developed a confidence with his medium that lets him play not only with the interior calligraphic form but also with the structural rules within which they live. Shapes, gaps, multi-line things gradually intrude into the overall text-like flow, their waxing and waning presences driven by a subtly astrological metronome, where the passage of time from page to page has a enjoyably slow, quasi-geological feel. All in all, a nicely done piece that hints that Jacobson has more to come.

You can download your own free copy of Action Figures from the Literate Machine website here, though you’ll have to pay a princely £2.99 to download your own Lulu-ized copy of The Giant’s Fence.

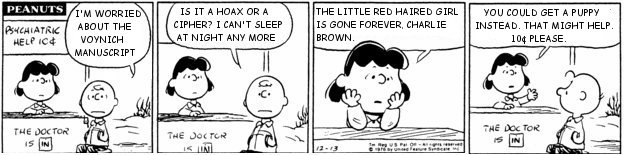

Personally, I see asemic writing (the overall category in which these books live) as sitting on quite a different table to cipher/language mysteries, so I’m not hugely sympathetic to the suggestion that (for example) the Codex Seraphinianus, the Phaistos Disc, or the Voynich Manuscript are themselves asemic. However, it is certainly true that people project all kinds of bizarre historical narratives onto these, to a degree to which asemic writers can only faintly aspire: perhaps such vicariously vivid visions ultimately form a family of warped interpretational artworks all their own, a kind of semantic complement to asemic writing. “Asemic reading”, perhaps?