Yet another interesting comment from Rene Zandbergen yesterday (to my flying potions post) sparked off a furious flurry of bloggery here at Cipher Mystery Mansions. While browsing through a large set of online manuscripts digitized (and hosted) by the University of Heidelberg, he found Cod(ex) Pal(atinus) Germ(anicus) 597 – an alchemical manuscript where a large amount of it is written in cipher (which you can download as a 15MB PDF file). Rene writes:-

Now this is a clear example of a MS where cipher has been used to hide secrets. It leaves me with the question:

Why does the Voynich MS not look like this?

My tentative answer: the Voynich MS isn’t actually just a cipher MS. FWIW.

(–Actually, I have my own answer to this, but we’ll get to that in a minute.–)

It seems to me that (unless Augusto Buonafalce happens to know better) the literature on Cod. Pal. Germ. 597 is pretty thin: even the Karl Bartsch catalogue entry for it (marked 287 here) isn’t much use. The Ms also merits the briefest of mentions on p.355 of the 1994 book “Geschichte der deutschen Literatur von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart” (it’s in Google Books). None of which, however, addresses its cipher aspect… but I guess that’s my job. 🙂 So, let’s have a look at it…

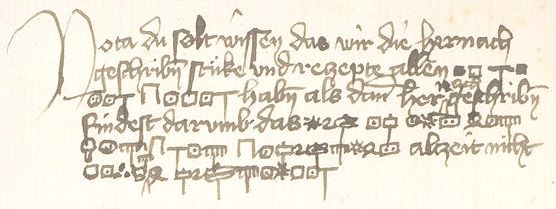

The Ms commences on folio 2r with some crossed-out ciphertext above some commentary in a different hand. (Some later pages hold only a few lines of ciphertext, so it seems likely that this originally contained just the ciphertext.) And then on folio 4v, the ciphertext (interleaved with Latin and German plaintext) starts in earnest:-

This is a basic-looking system comprising about 23 symbols, that shows every sign of being a simple (i.e. monoalphabetic) cipher consistent with its date (1426). The cipherbet was designed not for convenience of writing (for there are numerous fiddly characters, including a blocked-in black square), but around an apparently improvised ‘personal shape alphabet’. This points not to a cipher professional (working, say, in a Chancellery) but rather to an amateur cryptographer designing his/her own ‘homebrewed’ system:-

The letter shapes fall into three rough groups (as per the lines above):-

- Abstract shapes / known shapes

- Dots and containers

- Semi-representative (aide-memoire?) shapes (hammers, spade, rake?)

But then, just as you’re getting the hang of that, a completely different monoalphabetic cipher appears (from folio 6v onwards). This looks to be a refinement of this first system… but this post is getting a bit too long, so I’ll defer discussing that to another day.

Is this a “cipher mystery”? Yes, but only a very temporary sense, for I find it terrifically hard to believe that this wasn’t picked up by one or more of the numerous 19th century German codebreaking historians and cracked in a trice (or perhaps even a millitrice). Tony Gaffney would surely munch such a light confection before breakfast. 🙂

Finally, to respond to Rene Z’s question: why does the Voynich Manuscript not look like this? I’d prefer to start by looking at what this does resemble: Giovanni Fontana’s lightly-enciphered books of secrets, which were also from very same period. This mixing of text and ciphertext also occurs in Buonaccorso Ghiberti’s copy of his famous grandfather’s Zibaldone, which has some sections in a simple cipher, most notably what Prager & Scaglia call the “secret hoist” (on folios 95r and 98r of BR 228, for which see “Brunelleschi: Studies of his Technology and Inventions”, pp.67-70). From the simplicity of that cipher (“use the previous letter in the alphabet”), I’d suggest that Buonaccorso probably copied this from an older document, one probably made in the 1430s or 1440s (Lorenzo Ghiberti died in 1455).

Remember that this was the century when paper began to become affordable, and when ordinary people began to develop their own ciphers: and although it has become fashionable to criticize the development of individualism in the early Renaissance, I think it is fair to say that the desire to keep secrets for personal / familial gain runs in close parallel with this. Ghiberti, Fontana and the author of Cod. Pal. Germ. 597 all seem vastly similar in this respect.

Returning to Rene’s initial question, then, I suspect the correct question to be asking should be: why does the Voynich Manuscript not look like any of those ciphered manuscripts?

My own answer is that it is probably because the VMs will turn out to be from circa 1460 (i.e. 20-30 years after all of the above), and its author seems to have benefitted from contact with the sophisticated code-makers in the Milanese Chancellery, who developed and refined ideas in their own cryptographic bubble. Really, the VMs is from a very specific time and place – far too clever to be early 15th century, but still strongly mindful of what earlier ciphers looked like.