Back in May this year, I suggested to my friend Philip Neal that a really useful Voynich research thing he could do would be to translate the passages relating to Jacobus Tepenecz (Sinapius) that Jorge Stolfi once copied from Schmidl’s (1754) Historiæ Societatis Jesu Provinciæ Bohemiæ (though Stolfi omitted to the section III 75 concerning Melnik) from Latin. The documentation around Sinapius is sketchy (to say the the least), yet he is arguably the earliest physically-confirmed owner of the Voynich Manuscript (even if Jan Hurych does suspect his signature might be a fake): and Schmidl’s “historical” account of the Jesuits in Prague is the main source of information we have on this Imperial Distiller.

So today, it was a delightful surprise to receive an email from Philip, pointing me at his spiffy new translations of all the primary 17th & 18th century Latin sources relating to the Voynich Manuscript – not just the passages from Schmidl, but also the Baresch, Marci and Kinner letters to Athanasius Kircher (the ones which Rene Zandbergen famously helped to uncover).

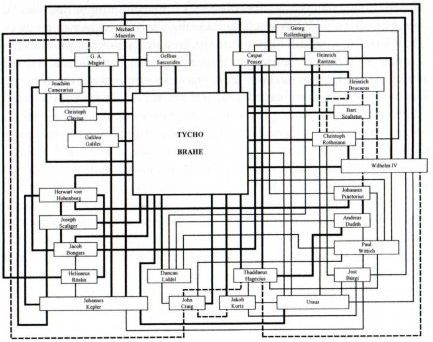

Just as I hoped, I learned plenty of new stuff from Philip’s translation of Schmidl: for example, that Sinapius was such a devout Catholic and supporter of the Jesuits in Prague that he even published his own Catholic Confession book in 1609 – though no copy has yet surfaced of this, it may well be that nobody has thought to look for it in religious libraries (it’s apparently not in WorldCat, for example). (Of course, the odds are that it will say nothing useful, but it would be interesting to see it nonetheless.) Sinapius was also buried in a marble tomb “next to the altar of the Annunciation” in Prague, which I presume is in the magnificent Church of Our Lady before Tyn where Tycho Brahe was buried in that same decade.

Interestingly, rather than try to produce the most technically accurate translation, Philip has tried to render both the text and the tone of each letter / passage within modern English usage, while removing all his technical translation notes to separate webpages. I think this was both a bold and a good decision, and found his notes just as fascinating as the translations themselves – but I suppose I would, wouldn’t I?

One thing Philip wasn’t aware of (which deserves mentioning independently) is Kircher’s “heliotrope”, mentioned in Marci’s 1640 letter to Kircher. The marvellous “heliotropic plant” which Kircher claimed to have swapped with an Arabic merchant in Marseille “for a watch so small that it was contained within a ring” (“Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything”, Paula Findlen (2004), p.13) was the talk of the day: this was a nightshade whose seeds allegedly “followed the motions of the sun when affixed to a cork bobbing in water”, in a kind of magnet-like way. This seems to have occupied the letters of natural philosophers even more than Galileo’s trial (from the same period). Yet to this day, nobody knows if Kircher was conning everyone with this heliotrope, or if he had been conned by someone else (but was perhaps unable to admit it to himself).

Then again, Kircher’s inclusion of the “cat piano” in his Musurgia Universalis might be a bit of a giveaway that he was a sucker for a tall tail tale. 🙂