Back in 2003, the (Paleo) Ideofact blogger (William Allison) reminisced about having once jointly compiled a list of meaningless dissertation titles, such as “The Semiotics of (En)Gendered Archetypes: A Contextual Deconstruction of the Voynich Manuscript.” His pleasantly-meandering blog train of thought quickly sped on to the possibility of Voynich fiction, continuing…

Later, I thought of writing a few detective stories centered on a career grad student who promised for his dissertation a translation and analysis of the manuscript. Never got around to it, though — maybe in my retirement.

Now there’s a challenge, I thought… so, six years on, here’s my version of how Chapter 1 might go…

[Here are links to chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Enjoy!]

* * * * * * *

The Voynich Translation

Chapter 1 – “Lesser Fleas”

7.07pm: Mrs Kurtz tapped Graydon Warnes Harvitz II sharply on the shoulder, waking him from his open-eyed slumber. “Stop sucking the end of your pencil so loudly“, she wheeshed through gritted teeth, “it’s disrespectful”. Vaguely nodding in approval, Graydon looked around at the empty chairs beached by the day’s ebbing tide of students – disrespectful to whom, he wondered? Perhaps she-of-the-library could see people that he couldn’t, he mused, possibly the ghosts of dead Yale grads, haunted by their own unfinished dissertations – a virtual “Skull and Bones” society? And look, over in the far corner, might that be dear old Montgomery Burns himself? Yesssss.

As the fug of dead presidents began to fade from his mind’s eye, Graydon’s own awful situation lurched back into sharp focus – of how to decipher the murderously intractable Voynich Manuscript for his PhD. All of a sudden, the purgatory endured by the library’s wraiths, endlessly waiting for long-stolen books to be returned to the stacks, seemed painfully close at hand. His boastful prediction (that this would be easy-peasy for someone as bright as him) had come back to haunt him.

All the same, his whole adventure had started brightly, zipping through all the literature on “The World’s Most Mysterious Manuscript” (so ‘P. T. Barnum’, wouldn’t you say, and isn’t there a Voynich Theorist born every minute?) Yet within a month, he had been reduced to trawling all the works of fiction appropriating the manuscript (typically as a tedious millennia-crossing conspiratorial MacGuffin). Then finally, not unlike an air crash survivor having eaten the seat-covers and the corpses of the other passengers before moving on to the dreaded airline food, Graydon had slurped his way messily through all the Voynich webpages. And the less said about that low-roughage diet the better.

Once the inevitable research euphoria had subsided, he had slid downwards into a bit of a decline – for if you don’t know what your subject is about, how can you read any secondary literature? He felt less like a Yale polymath than an intellectual vacuum cleaner, sucking up all the marginal detritus left over by other scholars, trying in vain to rearrange the collected dust and mites into patterns that would endure longer than a single big sneeze. And so the years had passed – not quite a decade, but far too long by any reasonable measure.

Eating and shaving less (but drinking and swearing more), Graydon began in time to resemble his fearsome alcoholic grandfather Mani Harvitz, the semi-legendary Allied code-breaker who as a young man had worked with John Manly and Edith Rickert breaking German diplomatic codes in World War I.

Once, he had mused whether his own grandfather might have looked at what Wilfrid Voynich had called (rather optimistically, it has to be said) “The Roger Bacon Manuscript”? Graydon had tirelessly gone through all that group’s archived correspondence, finding only that the brilliant young Mani, newly emigrated from Europe, had something of a huge schoolboy crush on the no-less-stellar Miss Rickert.

But this was merely symptomatic of the Mandelbrot Research Maze Of Doom he was stuck in, where each dead-end you go down sprouts off an infinite number of smaller dead-ends for you to recursively waste your time on. He found himself humming Augustus De Morgan’s rhyme “Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite ’em,: And little fleas have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum‘. Graydon wished he didn’t know that this was in turn based on a rhyme by Jonathan Swift: his mind had become crammed with a near-infinite constellation of similarly useless fact-bites, all held in interplanetary hibernation, eternally waiting to arrive at an unseen off-world colony.

And now he had just ten short days to prepare a presentation for his supervisor about all the dramatic progress he had claimed to have made over the past six months, when all he actually had to show for his efforts was a pencil dangling from his unkempt, beardy mouth. Perhaps… perhaps that was his subconscious’ way of telling him to take up smoking again?

Lesser fleas, he thought to himself as he removed the pencil and took a closer look. Because he preferred harder pencils for note-taking (laptops gave him back-ache), he had a “2H” rather than an “HB”. The Pencil Code (all the way from 9H to 9B via HB ) was over a hundred years old, yet still sounds like a legal-ese sequel to The Da Vinci Code. More linked trivia tumbled out of his tangled skein of memory: pencils themselves were made of graphite, not lead (that was a 400-year-old misunderstanding, you don’t actually have “lead in your pencil”). But before the pencil came along, people had often used red lead to mark things…

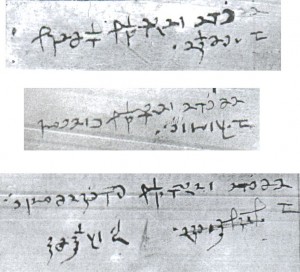

That was it: the red lead drawings on page f55r of the Voynich Manuscript. The only other remaining construction marks (which had generally been so assiduously removed by the author, it would appear) were the horizontal lines drawn on f67r2, under a kind of odd-looking circular calendar with a starfish design in the centre: these lead lines were definitely symptomatic of something… but of what?

Yes, these were the real deal – they were what his subconscious mind was telling him to examine right now, what he needed to be thinking about for his looming presentation. But what did they mean – and how on earth might such an incidental detail possibly help him translate the Voynich Manuscript?

Graydon’s mind raced through his Wikipedia-esque web of details – “red lead” A.K.A. lead tetroxide, better known to classicists as ‘minium’, from which we get ‘miniature’, a medieval style of small picture with lots of red finish. And what was that paper he’d never quite got round to reading? Yes, J. J. G. Alexander’s (1983) “Preliminary Marginal Drawings in Medieval Manuscripts“: that, and the ten thousand other cul-de-sacs to park your car in for a day he’d one day hope to read.

But the important point about f55r was that it was plainly unfinished. If red lead had been used to sketch out the shapes, then this was probably one of the last pages added: yet why would the author, so meticulous and rational in so many other ways, have left this one page in this state? Perhaps he/she had died (or had just given up, as Graydon had wanted to do so many times) before completing it?

Hold on, he thought – given the first page and the last page, perhaps we can use the changes in handwriting and in the cipher system between them to try to reorder the pages inbetween, to reconstruct the document’s construction order, and its flow of meaning… For the first time in perhaps even a year, his mind felt on fire, alive with the possibilities: he felt he was glimpsing something extraordinary, subtle and deep…

And that was when he saw Emm for the very first time, as she walked over to his desk to kick him out of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library for the night. She was extraordinary, like a long-haired Halle Berry but with piercing, intense eyes, eyes that could slice watermelons.

“That’s odd”, he said, “I didn’t know supermodels worked in libraries”.

“That’s odd”, she deadpanned, parroting his tone, “I didn’t know they let bears handle manuscripts.”

“Oh, the beard thing? Yeah, my barber died and I never found a replacement.”

“Woah, the ’90s must have been a really tough decade for you. Anyhoo, it’s time to kick your bear ass out of the library.”

Graydon blinked. He didn’t know if this conversation was going really well or really badly. “Hi, I’m Graydon Harvitz”, he said, “I’m…”

“…’the eternal Voynich grad’, Mrs Kurtz told me already. Is it true they’re hoping to get rid of you next week?”

“Well, they’re certainly going to try – perhaps it’ll be third time lucky.”

She paused, looking him up and down in the way a butcher would look at a freshly-hung carcass. “That would be a shame – Mrs Kurtz would miss you”, she said with half a smile, turning to walk away. “Though not your pencil sucking.”

“And your name is…?”

“Call me Emm – I’m the new cleaner.”

She was a cleaner? Errm… what? “Do cleaners like to eat lunch?”

“We’re always starving. Tomorrow should be good, because they’ll be kicking you out at noon – a French film crew will have your precious manuscript for the afternoon.”

A French film crew?

* * * * * * * *

Update: the story continues with Chapter 2 (“Game On”)…