Now here’s something that doesn’t pop up every day: ex-Mormon cipher fiction. In “Latter-Day Cipher“, Latayne C. Scott has crafted quite an interesting piece of work, combining the US police procedural genre (where in this case the main protagonist is a female journalist parachuted in from outside) with a kind of veil-lifting piece on the inner workings of the Mormon Church. It’s populated by a cast of characters so tortured by their own doubts about the, let’s say, veridicality of the gospels, history, and practices of the Church of Latter Day Saints (‘LDS’) that they behave in extreme ways (thus driving the plot), with some of them leading double lives.

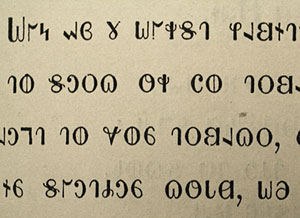

The “cipher” of the book’s title doesn’t refer to our old favourite the Anthon Transcript: rather, the notes left with the (near-inevitable) series of dead bodies are written in the Deseret Alphabet, a late 19th century phonetic alphabet constructed at the University of Deseret (which morphed into the University of Utah – “Deseret” is a term supposedly used in the Book of Mormon to denote “honeybee”, and in fact Utah’s state symbol is still a beehive) to help immigrants learn English quickly and reliably. The real thing looks like this (from 1868, courtesy of Wikipedia), which begins “W-u-n / ah-v / thee / w-u-r-s-t…”)

Given that this is a phonetic alphabet, and only one of the Deseret Alphabet notes in “Latter-Day Cipher” is written in a slightly encrypted way (I don’t think it’s a huge spoiler to say that it’s phonetic Spanish), Scott’s book isn’t really historical cipher fiction per se. But all the same, she’s clearly achieved her writing aims, and her story moves along briskly. She paints pictures of the troubled internal dynamics of people wobbling either side of the edge of the Mormon doctrinal line, interleaving its contradictory paradoxes (polygamy, racial purity, blood atonement, etc) with a ticking bomb and lines from Tennyson and T.S.Eliot.

With all these different themes running through it, you may well ask, is “Latter-Day Cipher” any good? Well, yes it is, actually. It would probably help if you knew a (very) little about the whole Mormon thing beforehand, but I do so enjoy getting to read nicely-written novels that aren’t all testosterone, flashy editing and world-renowned Harvard academics solving historical ciphers at gunpoint. Enjoy!

PS: in the great pantheon of literary attacks on the LDS, this is no more than a fly bouncing off an almost entirely indifferent whale, and I somehow doubt that it will manage to steer a single person away from the LDS’ comforting weltanschauung bosom. Still, wouldn’t it be awesome if South Park was right, and God is a Buddhist presiding over a Mormon-only heaven? Ummm… probably! 🙂