OK, stripping the Somerton Man’s story back, I’m still minded to believe that the Somerton Man was some kind of crim: and that the most credible piece of external evidence we have as to his identity is that in early 1949 two Melbourne baccarat players recalled he had been a nitkeeper at a Lonsdale Street baccarat school for about ten weeks some four years before (so around the start of 1945).

The next piece of relevant information is that Victoria’s state laws against nitkeeping were very strong: a first offence meant a fine of £20, a second offence a fine of £250, while a third offence meant six months in prison. Because the school principal paid the nitkeeper’s fines, what this meant was that a nitkeeper who had been fined once was effectively unemployable: no betting principal would hire a nitkeeper who had previously been fined, the fine for the second offence was just too high.

Hence the “Previously Fined Nitkeeper” Somerton Man hypothesis is simply that the reason the nitkeeper disappeared after about ten weeks was because he had been fined, and had thus become unemployable as a nitkeeper. So all we would have to do is find Victoria archive records of nitkeepers being fined in, say, 1944-1946, and we would have a reasonable shortlist of people who might – if everything aligned just perfectly – be the Somerton Man.

Victoria Police Gazette

Simple, eh? Well… in principle, yes. But as with just about everything, the Devil sits firmly in the details.

The #1 place we would like to look is the Victoria Police Gazette, where all court activity is helpfully summarized. However, for the specific years we are interested in here (1944-1946), there is only a physical copy that can be accessed at the Victoria State Library (the microform version runs only to 1939).

Moreover, I believe that the Compendium (that indexes this properly) is only available up until 1924, so searching it would be a painstaking process. One that I’d be more than happy to do, mind you, if I didn’t just happen to be on the far side of the planet.

So until someone decides to bite this particular monster-sized bullet, the Victoria Police Gazette avenue seems to be closed to us.

Baccarat in Victoria

As normal, we can look to the indexed wonder that is Trove for assistance in our search: and having already trawled through the Geelong Petty Sessions Register for 1945 (which is another story entirely), the charge we’re most interested in is “acting in conduct of [a] common gaming house”.

Prior to 1944, this charge almost always related to two-up (an Australian form of coin gambling), fan-tan and hazard. But as far as card schools go, the move to make baccarat illegal in Victoria started only in June 1944:

It was announced today that a bill declaring baccarat and certain other games unlawful games would be the first measure introduced when State Parliament reassembled next week. Baccarat and certain other games, said the Chief Secretary (Mr Hyland) had become a public menace and would be prohibited by law. Police reports showed that wagering on these games was stupendous, particularly on baccarat. At present, prosecutions in regard to baccarat could not be obtained as It was necessary to prove that the promoters were receiving a percentage of the wagers and this it was difficult to do.

Under the amended law, baccarat and the other games would be declared unlawful and it would be necessary only for the police to prove that the game was being played for the promoters to be dealt with and the place declared a gaming house.

By July 1944, there was also suggestion that the police were being bribed to take no action against Melbourne’s “palatial baccarat schools“, though of course senior police denied all knowledge (ho ho ho, right):

No complaint implying an accusation of bribery against any member of the gaming branch had come to his knowledge, said the Chief Commissioner of Police (Mr Duncan) today, when asked about the request by the Leader of the Opposition (Mr Cain) in the Legislative Assembly on Tuesday for an inquiry “into allegations that police had been paid large sums not to take action against palatial baccarat schools” in Melbourne. Mr Duncan said he was unaware of any such allegations. Mr Cain also said that advice he had received from an eminent King’s Counsel was that baccarat schools could be closed by the proprietors being charged with keeping a common gaming house. He was assured, Mr Duncan replied. that every possible endeavour had been made, and was still being made, by the gaming branch to detect and prosecute persons who took part in all forms of illicit gambling. In one prosecution recently, a court ruled that the playing of baccarat did not constitute a common gaming house.

The case where this had been tested in court was that of Christos Paizes, of View street, Hawthorn, relating to the card school he had run in Swanston-street in the city. Police had “watched the playing for money of ‘Ricketty Kate’, poker, solo and rummy” back in February 1944, but the case against Paizes had been dismissed. (More here.)

The bill was introduced to the Legislative Assembly on 4th July 1944, with Mr Hyland describing in some detail the opulent and expensive houses where the games of baccarat, dinah-minah and skillball were played. Having said that, there was immediate concern that the new legislation may not have given the police any genuine new powers that they didn’t already have. Even so, the bill passed all stages in the Assembly on 12th July 1944.

The police’s powers were then discussed here, with a very specific discussion of exactly how baccarat and dinah-minah were played in those “sumptuously furnished and luxuriously carpeted throughout” locations in the Gippsland Times of 20 July 1944.

The key article seems to have appeared in The Truth (24th June 1944), because Mr Hyland (and indeed the Crown Solicitor) responded directly to it here, discussing the baccarat schools at 158 Swanston Street (Paizas), and 7-9 Elizabeth Street (Stokes). Unfortunately, I don’t believe that this particular item is yet in Trove. 🙁

Hence: because baccarat schools were legal up to July 1944, the person whom the two baccarat players identified as a nitkeeper could not have been prosecuted (because even though they did have nitkeepers, baccarat schools were still legal). So we can fast forward past the first half of 1944.

Victoria: Baccarat Prosecutions

It immediately became a point of intense public interest as to whether any of the (now illegal) baccarat schools would be closed down.

On 30th July 1944, the police indeed went to premises in Swanston-street, city, and arrested a 26-year-old- Albanian called Fete Murit of Drummond-street, Carlton (plus 23 men and 17 women). They also raided premises in Drummond-street, Carlton, bringing in 14 more men. Murit was subsequently fined £50: somewhat quaintly, the article lists the occupations of the players brought in.

A similar case against Cyril Lloyd of Glenhuntly Road, Caulfield and Henry Clyde Jenkin of Balfour Street, East Brighton of running a baccarat school at the former’s address on 31 July 1944 was dismissed.

14 Sep 1944: one woman was charged with having permitted the premises (in Barkly Street, Elwood) to be used as a common gaming house, plus 13 men and 10 women who were found there. The article also notes that the charges against the 23 people arrested in Drummond-street, Carlton and the 19 found in a house in Munro Avenue, Carnegie were still awaiting hearing. It was believed that police had managed to close down all Melbourne’s big baccarat schools.

15 Sep 1944: Isaac Cooper-Smith, a fruiterer of Drummond-Street, was fined £20 for running a baccarat school at that same address (the raid was on 04 Sep 1944). 22 others were arrested, of which 13 were fined £1, seven £2, one £3, and one £4. However, Cooper-Smith’s conviction was subsequently quashed because he wasn’t actually on the premises when the police arrived.

03 Oct 1944: Stanley Paul Bonser, of Elbeena Grove, Murrumbeena, was fined £30, after a raid on a house in Munro Street, Carnegie on 30 Aug 1944: 17 others were fined £1.

16 Nov 1944: charges against Basil Koutsoukis relating to a baccarat school he was alleged to have been running in Lonsdale Street were dropped.

17 Nov 1944: only two of 19 men caught in a baccarat raid on premises in Park Street, Parkville on 02 Oct 1944 were fined (having admitted to playing baccarat), others saying that they were there “reading the paper”, “came to buy a car and stayed to supper”, or were “just waiting for a friend”.

29 Nov 1944: Mr Hyland said that baccarat schools had moved to private homes. “In the last five weeks a number of private homes had been visited, and 84 persons charged with gaming offences. Of these 75 had been convicted and nine cases held over“.

23 Mar 1945: Frank Gall was charges with permitting a house in Williamstown to be used as a common gaming house on 05 Feb 1945: Raymond A. Barrett and Albert Chandler were charged with aiding and abetting him. In court, all were fined £1, except Stewart Kerison and Joseph Picone who were fined £2 (“because of previous contacts with the police”). This was then appealed and overturned.

09 Apr 1945: three raids, two on Burnley and one Port Melbourne, 29 men held (no women, so probably two-up?).

14 Apr 1945: 48 men were caught in a raid on upstairs rooms in Russell Street, city “in the block next to police headquarters”. 35 men were also caught in another club in Lonsdale Street, “opposite the Old Royal Melbourne Hospital”, not 200 yards away.

22 Jun 1945: Christos Paizes suffered sudden back pains just before coming to court in relation to proceedings against his alleged baccarat school at 158-160 Swanston Street, City, had been instituted on 18 May 1945. Adjourned until 16 July. When this came to court on 19 July 1945, the affidavit submitted that Paizes was running a baccarat club at the old Canton Café in Swanston Street. The persons having control and management (none of whom were known by police to have a lawful occupation) of the club were:

- Christos Paizes (alias Harry Carillo)

- William John Elkins

- Gerald Francis Regan (of High-street, St Kilda)

- Richard Thomas (alias Abishara)

- “and a man known as Balutz”

The club was declared to be a common gaming-house as from 01 Aug 1945, even though Christos Paizes (of Mathoura-road, Toorak) denied it.

06 Sep 1946: police claimed the Melbourne baccarat boom was busted:

Not more than half a dozen small baccarat schools were now operating in Melbourne so far as they knew, gaming police said today.

They were commenting on the Sydney report that the New South Wales Police Department was concerned about the growth of large scale baccarat activities in Sydney.

Baccarat flourished in Melbourne until amendment of the law declared It an unlawful game two years ago. That smashed it here as an organised gambling racket. Then the death of Melbourne’s “baccarat baron,” Harry Stokes, brought to an end schools that were still trying to carry on.

Most recent blow at city gambling centres was a Supreme Court declaration at the request of the police which “quarantined” a social club in Swanston Street as a common gaming house. This meant that any persons entering the premises was liable to arrest.

To escape the punitive effect of this order, the owner sold the premises to a buyer approved by the Crown Law authorities.

POLICE FIND OUT

Places where baccarat was played now, the gaming police said today, were private homes and one or two suburban halls, and they were not able to carry on for long undiscovered. Clients were picked up in cars, chiefly at foreign clubs and solo and bridge schools to evade detection, but the police soon found out.

Whenever the playing of baccarat was discovered, the occupier of the premises was arrested for conducting a gaming house, and everyone there was charged with being found in a gaming house.

Constant police action had put an end to baccarat In Melbourne as a reliable business venture.

07 Oct 1946: “twelve fashionably dressed women and 25 men” were brought in by police after a raid on an alleged baccarat school in Lavender Bay. They were playing a game called “chuck-a-chuck”, similar to baccarat but more profitable for the house.

20 Dec 1946: Dennis Greelish of 578 Melbourne Road, Spotswood was fined £10 for what was clearly baccarat, even though the bench accepted it was probably a game “between friends”.

After The Golden Age

I think it is a reasonably safe bet that the period the two baccarat players were referring to was after July 1944 (when the legislation making baccarat illegal was introduced into Victoria), but before September 1946 (when baccarat was clearly at the end of its life there). The Golden Age – of swank socialites playing baccarat in luxuriously carpeted surroundings – had come to an end with the legislation: in July 1944, it was not a question of whether baccarat would fall, it was simply one of when – or rather, how long bribery could keep the baccarat balls hanging impossibly in the air.

Even though gambling at Christos Paizes’ Lonsdale Street baccarat school had attracted intense (and sustained) attention from the police in early 1944, they had been unable to find any way to shut its (still legal) activities down. Moreover, even once the new legislation had been passed, Paizes continued his baccarat activities through the rest of 1944 and into 1945. Finally, his club was closed down in August 1945: the golden age may already have passed, but that (along with the death of Harry Stokes) was the end of the Melbourne baccarat era.

As far as William John Elkins, Richard Thomas (alias Abishara), and the man known as “Balutz” go:

- William John Elkins had been arrested for running a Melbourne gaming house in January 1938, and attempts to extradite him to Adelaide in August 1941 on a separate charge had failed. But he seems to have still been alive (and living in Wilgah street, East St Kilda) in October 1950.

- Deeb John Abishara (who was living at 9 Robe street, St Kilda in June 1941, when he applied for naturalization) was also known as Richard Thomas. Dick Thomas was still “one of the biggest baccarat barons in Melbourne” in September 1953 (and, from the article, would seem to have clearly been deeply feared).

- Might Balutz be the Somerton Man?Of “Balutz”, there is no sign at all.

Balutz the Romanian?

Might Balutz be the Somerton Man? He was certainly closely associated with Christos Paizes’ Lonsdale Street baccarat school (though without being an obvious principal), at almost exactly the right time flagged by the two anonymous baccarat players. He was certainly mysterious enough: anyone searching for his name will find precious little to work with. Even though I could find nothing about him being a fined nitkeeper, I think he was closely associated with the Lonsdale Street baccarat school in the right kind of way.

Balutz is a Romanian surname: trawling through various databases, I can find evidence of Balutz family members emigrating to the US, but can find nothing in Australia or New Zealand. (Nothing in NAA, billiongraves etc.) No Balutz family trees jumped out at me, but perhaps you’ll have more luck.

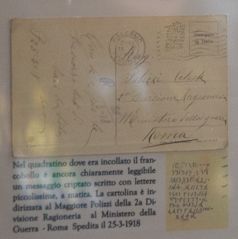

I previously blogged about the Melbourne baccarat schools that briefly flourished in 1947-1948: there, I mentioned the 1944-1949 photo supplement to the Police Gazette, plus the similar one for 1939-1948 held in North Melbourne. Might there be a picture of Balutz in there?

Or… if he was the Somerton Man, might his surname be in the employee list at Broken Hill? I’ve previously asked the Broken Hill Historical Society to look for Keanes for me, but it would be a surprise if anyone had asked them to search for Balutz. Who knows what they might find?

If anyone can find anything at all about Mr Balutz, please say!