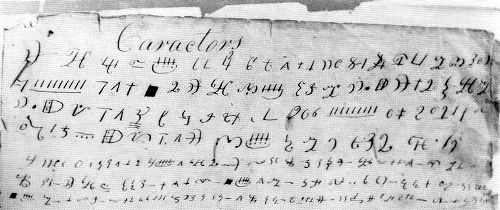

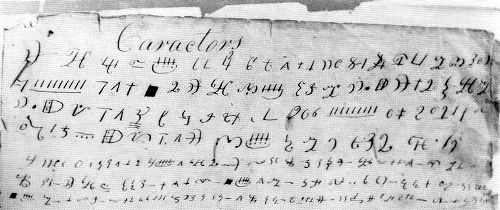

At the heart of the founding mythology of the Mormon Church sits a small fragmentary document called the Anthon Transcript. The claim linked with it is that it was copied from gold plates revealed by angels to the 18-year-old Mormon prophet Joseph Smith Jr in 1823, and that its “Caractors” were written in the “reformed Egyptian” of the (otherwise unknown) “Nephite” people, who had (allegedly) emigrated to America from Jerusalem two and a half millennia earlier.

Of course, extraordinary claims need at least some kind of evidence – and so the key historical question is whether or not the Transcript provides that. The other pages of the transcript (if they existed at all) have long disappeared, while the eponymous Professor Anthon (who had originally been said to have somehow verified Smith’s translation) later reported “that the marks in the paper appeared to be merely an imitation of various alphabetical characters, and had, in my opinion, no meaning at all connected with them“. After the Transcript had been shown to Charles Anthon, its “translation” was carried out by Joseph Smith who acted as a “seer” to channel it: to do this, Smith used either a giant pair of golden spectacles (that had been found with the golden plates), or one or two stones placed in the bottom of an upturned tall hat, the latter a scrying technique he used before and after 1823 when searching for buried treasure.

Regardless of all that, my particular interest in the Anthon Transcript is as a cipher historian looking at a single contentious document. Back in 2004, I exchanged a number of emails with Richard Stout, who has researched extensively on this subject to build up his own (very specific) claims. However, what follows below relates to my own opinion of what we can learn about the Transcript purely from its alphabet, and is competely independent of Richard’s ideas and interpretations. (And no, I’m neither a Christian, a Mormon, nor even an ex-Mormon.)

What kind of document is this? Much as people ask of the Voynich Manuscript, is it shorthand, cipher, a lost ancient language, or some kind of deception? Furthermore, is it an original document, a copy of a document, a copy of some letter-shapes from a real document, or a purely made-up thing? The hope here is that we can use its alphabet to help resolve any of these open questions: so let’s see what we find…

Are the letters shorthand? Just about anyone who has grasped the history of shorthand would quickly conclude that it is not a tachygraphic (“fast writing”) system, insofar as it is (as can be seen from the many fussy and overflourished letter-shapes) clearly not optimized for writing speed. Because it appears neither concise, memorizable, speedy, nor unambiguous, it’s a pretty poor match for the whole idea of shorthand.

It should be clear, then, that the Transcript itself was not written in a shorthand system: yet I do hear what Richard Stout says when he suggests links between individual Anthon Transcript letters and letters taken from a whole range of shorthand systems (apparently including many Tironian notae).

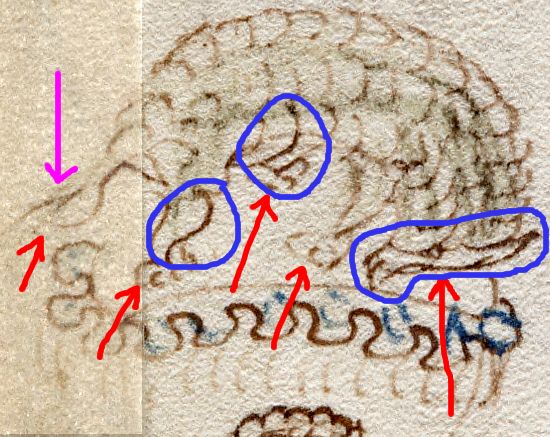

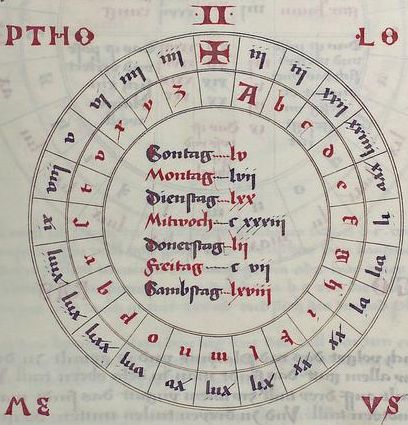

Yet I must caution that even an apparently well-defined character can trace out multiple independent paths through time. As a prime example, Stout notes that the filled-in box shape (which appears three times in the Anthon Transcript) appears in William Addy’s (1618-1695) shorthand system, where it denotes the word “altogether“. Addy’s system (first printed in 1684) was based on Jeremiah Rich’s earlier system: curiously, Addy later published a shorthand version of the Bible (1687), though this was perhaps stenographic oneupmanship to trump Rich’s shorthand version of the New Testament (1673-1676). The problem we have is that, as we saw here only a few days ago, Cod. Pal. Germ. 597 also includes a solid square in its first alchemical cipher alphabet… some 250 years before Addy. So, what was the actual source for the Transcript’s filled square shape – 15th century alchemy, or late 17th century stenography?

All the same, Isaac Pitman’s “History of Shorthand” (I own a copy of the 3rd edition) describes Jeremiah Rich’s system as being “encumbered with long lists of arbitrary characters to represent words which could not be written in any moderate space of time by their respective letters” (p.22), an “absurdity” whose “practice seems to have been at its height in the days of Rich” (p.23), with its 300 “arbitraries“. To Pitman’s roving historical eye, Rich’s follower Addy merits only a single paragraph (p.26). But helpfully, Pitman continues with a long list of people who produced related systems: Nathaniel Stringer (1680), William Addy (1695), Dr Doddridge (published in Oxford in 1805!), Farthing (1654), George Delgarno (1656), Everardt (1658), Noah Bridges (1659), William Facy (1672), William Mason (1672), John West (1690), Thomas Gurney (1751) [though Gurney finally dropped the arbitraries!]… and notes that Rich’s system (and/or its many variants and descendants) were still being taught early in the 19th century.

So it would seem that Stout is broadly on target with comparisons with the over-complex systems initially devised by Rich and Addy. I think it would be fair to say that if the Anthon Transcript’s alphabet can at all be said to have a parentage, it lies in the family of overcomplex shorthand systems deriving from Jeremiah Rich, and specifically in the ornate (and occasionally impractical) arbitrary signs added to them.

There must have been more than a hundred subtly different (usually plagiarised) shorthand systems based on Jeremiah Rich’s original, with many of them still in surprisingly active use circa 1823: and so I would predict that finding the closest match to the source of (or the inspiration for) the Anthon Transcript would likely be a perfectly possible (if painstaking) job, given a copy of Pitman’s book as a starting point.

Are the letters Tironian notae? Stout suggest comparisons between various individual Transcript letter-shapes and the sprawling array of Tironian notae accumulated over the centuries. However, my judgment is that you could construct visual correlations between just about any non-pictographic alphabet and Tironian notae: and so I’m very far from convinced that there is any immediate causality implicit in the choice of letter shapes.

Are the letters “reformed hieroglyphics”? Given that I place the Anthon Transcript’s alphabet firmly within the visual & stylistic tradition of arbitrary-loaded shorthands (which themselves all ultimately derive from Jeremiah Rich’s mid-seventeenth century shorthand system, even if the Anthon Transcript’s text is apparently not written in a shorthand system), I have to say that I am at a loss to see any conceivable connection with hieroglyphics (or even with Demotic, for that matter).

Are the letters written in an Old Irish shorthand? Richard Stout points to one shape in particular (you can see an example on line 2 of the Anthon Transcript, two glyphs to the right of the filled square) comprising two left-curving lines joined by a horizontal line: he points to a resemblance with an Irish glyph used on “page 311” of the late fourteenth century Book of Ballymote, and continues by pointing to resemblances between rows of dots elsewhere in the same manuscript and in the Anthon Transcript.

Yet dots were used by medieval monks across Europe to encipher vowels: so I’m far from sold on the idea that rows of dots (which, in any case, were used a quite different way in the Transcript) link this to the Book of Ballymote at all.

Stout’s proposed Irish manuscript connection seems to be an apologium for other Mormon cipher claim, in which the other main source document was allegedly written in some kind of old Irish writing. But I don’t really see that connection here at all: before I get too excited about a single letter-shape, I’d want to have trawled through the relevant shorthand archives first.

Are the letters a cipher alphabet? The Anthon Transcript seems quite ill-judged for this, too: what on earth would any cipher alphabet be doing with a nine-vertical-strokes-plus underline shape (line 2)? This seems to be unnecessarily showy – and in fact, I would suggest that this sort of “prison-cell counting” shape is more the kind of thing you would see in a child’s made-up cipher to denote ’10’ (or possibly ‘X’).

Regardless, the whole document could possibly be written in a cipher: and so I think it would be a good idea to subject a transcription of the Transcript to some statistical tests. It would be more credible were this to be done by someone outside of the Mormon Church (in contrast to previous attempts, according to Wikipedia). It’s true that there are some repeated patterns inside the Transcript, sure: but might these amount to complete words, phrases, or even sentences? Right now, I’m not sure: it looks fairly fragmentary to me.

Are the letter-shapes all fake? I don’t think so: to my eyes, they do give the impression of forming a moderately coherent set of “characters” copied from one or more existing shorthand documents, but with child-like cipher shapes added, very probably to give the whole thing slightly more of an ‘exotic’ feel. More than anything else, I think it is this awkward blend of the nuanced and the naive that makes it seem unconvincing as a real piece of text.

Because the ratio of arbitraries to simple strokes also seems quite high to my eyes, I would also be unsurprised if the author had cherry-picked the interesting-looking letter-shapes from a shorthand source.

In summary, probably the least controversial inference you can draw from the lettershapes is their post-1650 dating: the embellished “H” shape and the probable links with Rich-family shorthand letter-shapes indicate that this is in no way ancient.

In the absence of any other credible information, the most likely story I can reconstruct is that the “caractors” in the Anthon Transcript were copied in no particular order from a shorthand Bible (or possibly a shorthand diary), with various other letter-shapes added to make the overall alphabet look more ‘exotic’, or even “hieroglyphic” (even though, to our modern eyes, these singularly fail to have the desired effect). I would also be fairly unsurprised if the same shorthand Bible itself was subsequently used as a prop to convince skeptics – in short, that this was the Detroit Manuscript itself (but which, like the rest of the Anthon Transcript, subsequently disappeared from sight).

Of course, a single good piece of evidence could well refute all of this… but I haven’t seen it yet.

What do you think?

Post update: a very big thank you! to Richard Stout for suggesting corrections to the first two paragraphs – much appreciated! 🙂