A few days ago I promised you my post-Frascati thoughts on the Voynich Manuscript radiocarbon dating. Errrm… little did I know quite what I was letting myself in for. It’s been a fairly bumpy ride. 🙁

Just so you know, the starting point here isn’t ‘raw data’, strictly speaking. The fraction of radioactive carbon-14 remaining (as determined by the science) first needs to be adjusted to its effective 1950 value so that it can be cross-referenced against the various historical calibration tables, such as “IntCal09” etc. The “corrected fraction” value is therefore the fraction of radioactive carbon-14 that would have been remaining in the sample had it been sampled in 1950 rather than (in this case) 2009. Though annoying, this pre-processing stage is basically automatic and hence largely unremarkable.

So, the (nearly) raw Voynich data looks like this:

Folio / language / corrected fraction modern [standard deviation]

f8 / Herbal-A / 0.9409 [0.0044]

f26 / Herbal-B / 0.9380 [0.0041]

f47 / Herbal-A / 0.9389 [0.0041]

f68 / Cosmo-A / 0.9338 [0.0041]

What normally happens next is that these corrected fraction data are converted to an uncalibrated fake date BP (‘Before Present’, i.e. years before 1950), based purely on the theoretical radiocarbon half-life decay period: for example, the f8 sample would have an uncalibrated radiocarbon date of “490±37BP” (i.e. “1460±37”).

However, this is a both confusing and unhelpful aspect of the literature because we’re only really interested in the calibrated radiocarbon dates, as read off the curves painstakingly calibrated against several thousand years of tree rings; so I prefer to omit it. Hence in the following I stick to corrected fractional values (e.g. 0.9409) or their straightforward percentage equivalents (e.g. 94.09%): even though these are equivalent to uncalibrated radiocarbon dates, I feel that mixing two different kinds of radiocarbon dates within single sentences is far too prone to confusion and error. It’s hard enough already without making it any harder. 🙁

The problem with the calibration curves in the literature is that they aren’t ‘monotonic’, i.e. they kick up and down. This means that many individual (input) radiocarbon fraction observations end up yielding two or more parallel (output) date ranges, making using them as a basis for historical reasoning both tricky and frustrating.

Yet as Greg Hodgins described in his Frascati talk, radiocarbon daters are mainly in the business of disproving things rather than proving things. In this case, you might say that all radiocarbon dating has achieved is to finally disprove Wilfrid Voynich’s suggestion that Roger Bacon wrote the Voynich Manuscript… an hypothesis that hasn’t been genuinely proposed for a couple of decades or so.

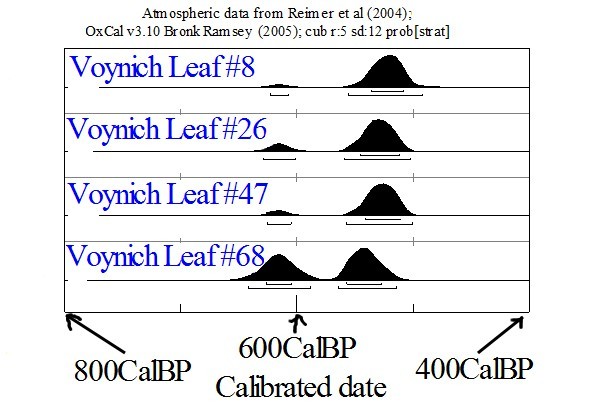

Of course, Voynich researchers are constantly looking out for ways in which they can use or combine contentious / subtle data to build better historical arguments: and so for them radiocarbon dating is merely one of many such datasets to be explored. In this instance, the science has produced four individual observations (for the four carefully treated vellum slivers), each with its own probability curve.

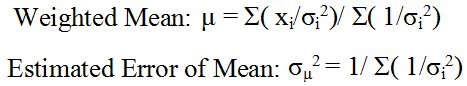

The obvious desire here is to find a way of reliably combining all four observations into a single, more reliable, composite meta-observation. The two specific formulae Greg Hodgins lists for doing this are:-

So, I built these formulae into a spreadsheet, yielding a resultant composite fractional value for all four of 0.93779785, with a standard deviation of 0.004169. I’m pretty certain this yields the headline date-range of 1404-1438 with 95% confidence (i.e. ±2 sigma) quoted just about everywhere since 2009. But… is it valid?

Well… as with almost everything in the statistical toolbox, I’m pretty sure that this requires that the underlying observations being merged exhibit ‘normality’ (i.e. that they broadly look like simple bell curves). Yet if you look at the four probabilistic dating curves, the earliest calibrated date (on f68) yields two distinct dating ‘humps’, whereas the latest calibrated date (on f8) has almost no chance of falling within the earlier dating hump. This means that the four distributions range from normal-like (with a single mean) to heteroscedastic (with multiple distinct means).

Now, the idea of having formulae to calculate weighted means and standard deviations is to combine a set of individual (yet distinct) populations being sampled into a single larger population, using the increased information content to get tighter constraints on the results. However, I’m not convinced that this is a valid assumption, because we are very likely sampling vellum taken from a number of different animal skins, very possibly produced under a variety of conditions at a number of different times.

Another problem is that we are trying to use probability distributions to do “double duty”, in that we often have a multiplicity of local means to choose between (and we can’t tell which sub-distribution any individual sample should belong to) as well as a kind of broadly normal-like distribution for each local mean. This is mixing scenario evaluation with probability evaluation, and both end up worse off for it.

A further problematic area here is that corrected fractional input values have a non-linear relationship with their output results, which means that a composite fractional mean will typically be different from a composite dating value.

A yet further problem is that we’re dealing with a very small number of samples, leaving any composite value susceptible to being excessively influenced by outliers.

As far as this last point goes, I have two specific concerns:

* Rene Zandbergen mentioned (and Greg confirmed) that one of the herbal bifolios was specifically selected for its thickness, in order (as I understand it) to try to give a reliable value after applying solvents. Yet when I examined the Voynich at the Beinecke back in 2006, there was a single bifolio in the whole manuscript that was significantly thicker than the others – in fact, it felt as though it had been made in a completely different way to the other vellum leaves. As I recall, it was not far from folio #50: was it f47? If that was selected, was it representative of the rest of the bifolios, or was it an outlier?

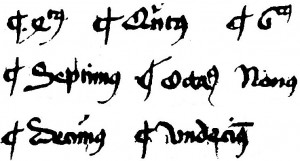

* The 2009 ORF documentary (around 44:36) shows Greg Hodgins slicing off a thin sliver from the edge of f68r3 (the ‘Pleiades’ panel), with the page apparently facing away from him. But if you look just a little closer at the scans, you’ll see that this is extremely close to a section of the page edge that has been very heavily handled over the years, far more so than much of the manuscript. This was also right at the edge of a multi-panel foldout, which raises the likelihood that it would have been close to an animal’s armpit. Personally, I would have instead looked for pristine sections of vellum that had no obvious evidence of heavy handling: picking the outside edge of f68 seems to be a mistake, possibly motivated more by ease of scientific access than by good historical practice.

As I said to Greg Hodgins in Frascati, my personal experience of stats is that it is almost impossible to design a statistical experiment properly: the shortcomings of what you’ve done typically only become apparent once you’ve tried to work with the data (i.e. once it’s too late to run it a second time). The greater my experience with stats has become, the more I hold this observation to be painfully self-evident: the real world causality and structure underlying the data you’re aiming to collect is almost without exception far trickier than you initially suspect – and I can see no good reason to believe that the Voynich Manuscript would be any kind of exception to this general rule.

I’m really not claiming to be some kind of statistical Zen Master here: rather, I’m just pointing out that if you want to make big claims for your statistical inferences, you really need to take an enormous amount of care about your experimental methodology and your inferential machinery – and right now I’m struggling to get even remotely close to the level of certainty claimed here. But perhaps I’ll have been convinced otherwise by the time I write Part Two… 🙂