In four words, the Voynich Manuscript is a puzzling old thing (and really, ain’t that the truth?). Filled with unknown plants, unrecognizable astrology & astronomy, and numerous drawings of small naked women, the fact that we also can’t read a single word of its ‘Voynichese’ text doubles or even triples its already top-end mystery. Basically, the Voynich Manuscript is to normal mysteries as a Scooby sandwich is to an M&S prawn mayonnaise sandwich.

People have their theories about it, of course. The last ripe strawberry of a mainstream Voynich theory came back in 2004 from academic Gordon Rugg, who declared that it was a hoax made using late 16th century cryptographic table-based trickery. Sadly 2009 saw an early 15th century radiocarbon dating of its vellum, which would seem to have made a fool of such fruity ingredients. Or if not a fool, then certainly a bit of a mess.

Despite almost-irreconcilable dating problems, numerous Voynich theories continue to find support from eager evangelists, angrily jabbing their fingers at any epistemological cracks they can see. The most notable get-out clause proposed is that some devious so-and-so could theoretically have used centuries-old vellum for <insert fiendishly clever reason here>, rather than some fresh stuff. This is indeed possible. But also, I think, rather ridiculous.

Why? Because it adds yet another layer of possible unlikeliness (for it is surely extraordinarily unlikely that someone back then would have such a modern sensibility about faking or hoaxing that they would knowingly simulate a century or more of codicological activity), without actually helping us to manage or even reduce any of the existing layers of actual unlikeliness.

Ironically, many such theorists prove anxious to invoke Occam’s Razor even as they propose overcomplex theories that sit at odds with the (admittedly somewhat fragmented) array of evidence we have. Incidentally, my own version is what I call “Occam’s Blunt Razor”: “hypotheses that make things more complicated should be tested last, if ever“.

For more than a decade, I’ve been watching such drearily unimpressive Voynich theories ping (usually only briefly, thank goodness) onto the world’s cultural radar. Most come across as little more than work-in-progress airport novella plots, but without the (apparently obligatory) interestingly-damaged-yet-thrustingly-squat-jawed protagonist to counterbalance the boredom of trawling through what passes for historical mystery research these days (i.e. the first half of Wikipedia entries).

And so I think it was something of a surprise when, back in 2006, I grew convinced that the Voynich Manuscript had been put together by the Italian architect Antonio Averlino (better known as Filarete), and even wrote a book about it (“The Curse of the Voynich”). But by taking that step, wasn’t I doing exactly the same thing as all those other Voynich wannabe theorists? Wasn’t I too putting out an overcomplex theory at odds with the evidence that signally failed to explain anything?

Well… no, not at all, I’d say. Averlino was the cherry on the dating cake I’d patiently built up over the years: the cake led me to the cherry, not the other way around. And that dating framework still stands – all the analysis I’ve carried out in the years since has remained strongly consistent with that framework.

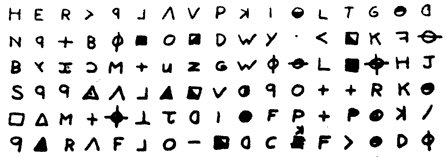

Even so, I’m not wedded to Averlino: my guess is that you could probably construct a list of one or two hundred Quattrocento candidates nearly as good a match as him, and it could very well have been one of those. Yet what I am sure about is that when we ultimately find out the Voynich’s secrets, it will prove to be what I said: a mid-15th century European book of secrets; collected from a variety of sources on herbalism, astronomy, astrology, water and even machines; whose travelling author was linked directly to Milan, Florence, and Venice; and whose cipher was largely composed of 15th century scribal shorthand disguised as medieval scribal shapes (though with an annoying twist).

Averlino aside, please feel free to disagree with any of that… but if you do, be aware that you’ve got some important detail just plain wrong. 🙂

Perhaps the most disappointing thing about the Voynich Manuscript is that historians still skirt around it: yet in many ways, it offers the purest of codicological challenges ever devised. For without the contents of the text to help us (and a provenance that starts only in the 17th century, some 150 years or so after it was constructed), all a professional historian can rely on is a whole constellation of secondary clues. Surely this is the best gladiatorial arena ever offered?

I’ll happily help any historian who wants to take the mystery of the Voynich Manuscript on, 21st century style. Yet it would seem that few have the skills (and indeed the research cojones) to do ‘proper’ history any more, having lost them in the dense intertextuality of secondary research. Without close reading to back their judgment up, how many can build a historical case from a single, unreadable primary source?

You know, I still sometimes wonder what might have happened if, in the 1920s, John Matthews Manly and Edith Rickert had chosen not Chaucer as their über-subject matter but the Voynich Manuscript instead. As a team, they surely had more than enough cryptological and historical brains to come devilishly close to the answer. And yet… other times it seems to me that the Voynich offers a brutally nihilistic challenge to any generation of historians: for the techniques you have been taught may well be a hindrance rather than a help.

All in all, perhaps (capital-H) History is a thing you have to unlearn (if only partially) if you want to make sense of the Voynich Manuscript’s deep mystery – and that is a terrifically hazardous starting point for any quest. For that reason, it may well be something that no professional historian could ever afford to take on – for as Locard’s Exchange Principle would have it, every contact between things affects both parties. A historian might change Voynich thinking, but Voynich thinking might change the historian in the process… which might well be a risky exchange. Ho hum… 😐