In the 1970s, Captain Prescott Currier noted that the Voynich Manuscript’s text seemed to contain two separate ‘languages’ (“A” and “B”), each containing sub-languages that varied yet further. For him, the language differences were primarily statistical rather than linguistic: to tell what we now call ‘Currier A pages’ & ‘Currier B pages’ apart, he observed that (using the EVA transcription):-

“(a) Final ‘dy’ is very high in Language ‘B’; almost non-existent in Language ‘A.’

(b) The symbol groups ‘chol’ and ‘chor’ are very high in ‘A’ and often occur repeated; low in ‘B’.

(c) The symbol groups ‘chain’ and ‘chaiin’ rarely occur in ‘B’; medium frequency in ‘A.’

(d) Initial ‘chot’ high in ‘A’; rare in ‘B.’

(e) Initial ‘cTh’ very high in ‘A’; very low in ‘B.’

(f) ‘Unattached’ finals scattered throughout Language ‘B’ texts in considerable profusion; generally much less noticeable in Language ‘A.’“

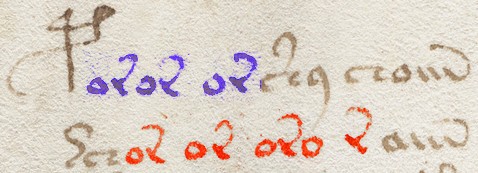

Similarly, he thought that the writing seemed to have been done by at least two hands (specifically, a larger, rounded hand he called “1” [mainly on A pages], and a more cramped, tighter hand he called “2” [mainly on B pages]), which he was convinced were those of at least two different people. He also pointed out that certain Voynichese letters appeared to have a very position-dependent behaviour, and that a line of text seems to be a functional unit in some way.

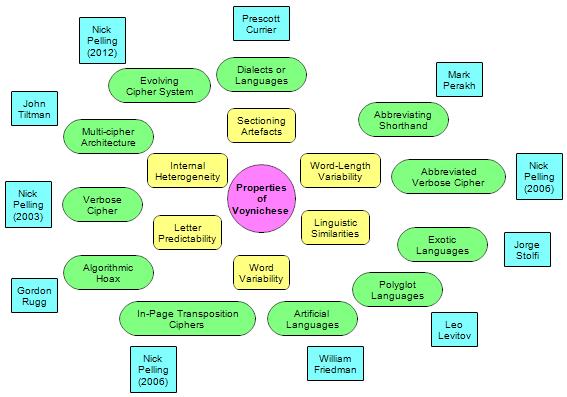

I would argue that Currier’s work has been arguably the single most influential piece of Voynich research of the last few decades, because it in effect erects a pragmatic conceptual framework for working with the Voynich Manuscript that every researcher who follows should strongly bear in mind, if not actually use.

So when I get told about so-called Voynich ‘research’ that treats the entire Voynich Manuscript as a uniformly homogenous linguistic entity (i.e. ignoring Currier completely), I give a little sigh of muted exasperation and move swiftly on. This is simply because Currier’s languages are to the Voynich manuscript what the Gillogly strings are to the Beale Ciphers: hence any claimed explanation or decryption that fails to account for Currier’s raw (yet actually rather unexpected, if you think about it) set of statistical observations is simply doomed to failure, period, even 40 years on.

I think it’s important to point out that Currier wasn’t some technical-minded Army codebreaker doing a bit of Voynich moonlighting: having graduated in Philology (with a focus on Romance Languages) from the University of Washington, he was surely perfectly placed to contribute a balanced analytical insight into the elusive internal structure of Voynichese. Hence I think the real reason that Currier’s work has been so influential in the field is that he really cared about what he was doing, and that he wanted to make a constructive, positive difference to Voynich studies.

Sadly, Currier’s insights failed to inspire a community-wide statistical assault on the Voynich Manuscript: researchers trundled on with their existing ad hoc studies, perpetually reinventing wheels – the big red revolution bus never arrived at the Voynich stop. The only obvious difference was that at least a few sensible people (Rene Zandbergen, Mark Perakh, etc) did manage to do statistical tests on A and B pages separately, which is a start, I guess… but only a start.

But because Currier restricted his work to statistical observations, he never built his framework up into the kind of thing Annales historians call a problematique, i.e. a fully rounded research question that drives future research forward. It’s all very well cleverly spotting the presence of different languages (some people prefer to say “dialects”, but it’s an open question) within the text, but that does beg some rather big questions, so-called “elephants in the room” that everyone can see but nobody talks about:-

* Why are the different languages fragmented across the document, often mixed up within a single quire?

* What gives rise to all the variation both within Currier A and within Currier B?

* Why was there a need for multiple languages at all? Why not just stick with Currier A?

Fast forward to 2013, and I think we can answer at least one of these questions, and provide reasonable (if tentative) answers to the other two.

Firstly: the simple reason that the Voynich languages are in disarray appears to be that the bifolios themselves are in disarray. I and others have uncovered numerous different codicological artefacts that strongly suggest the initial gatherings were disrupted, bound, rebound, and indeed misbound; and there is even specific evidence that quite a few bifolios ended up reversed relative to their original facing direction (i.e. folded back to front across the central crease).

Essentially, as the bifolios themselves were scrambled, so too were the languages: which is why A bifolios and B bifolios appear juxtaposed within individual bound quires. Yet given that there are large homogenous stretches of A and B bifolios, it seems likely that the scrambling wasn’t absolute – while I don’t think the Voynich bifolios were ever blown down a street in the wind, I do believe that what we see arose from a combination of planned shuffling (e.g. moving the large multi-panel bifolios towards the back and binding them there) and unplanned shuffling (binding breaking on some quires, spilling the bifolios onto the floor).

Secondly: I strongly believe that the structural and palaeographic differences between A pages and B pages tells a strong story of two major writing phases (let’s call them the “A phase” and the “B phase”). Identifying different composition phases through close reading is the kind of thing that modern historians do all the time, so this isn’t a fundamentally new approach: the only nuance here is that rather than close textual analysis (for Critical Reading) or art technique de-layering (for Art History), we’re instead looking at a cryptanalytical close reading. But then again, isn’t that what Currier was hoping for?

Note that I’m not speculating here about why there were two writing phases: at this point it’s enough just to identify them and give them names. But it does point to some interesting questions about why there should be both Herbal A pages and Herbal B pages, and what the difference between them might turn out to be (a topic upon which I’ve previously speculated more than enough for one lifetime, some would say).

Thirdly: within each of the A & B writing phases, I believe that the variations in the statistics will turn out to have arisen because of cryptographic evolution during each phase. By this, I mean that the core cryptographic system in use at the outset of each phase evolved during the various writing phases, as the author(s) finessed the system to work around specific cryptographic challenges encountered along the way, and so ending up a very different beast at the close.

I suspect that this will prove to be a set of “ratchet” effects, in that once changes were made to the system they would probably tend to stay in place until they in turn were replaced or finessed. I therefore believe that the cryptanalytical challenge we face is working out the evolutionary curves that the A system and the B system traced out – quantifying and then mapping them as if the system driving them were a probabilistic Markov state machine, its configuration relentlessly evolving as the text flows from page to page to page.

As to the specifics of how we should do this, you’ll have to wait for the next post…