There are two big problems with the Voynich Manuscript handwriting: (1) it doesn’t flow like normal handwriting; and (2) there are apparently a number of different “hands” in play.

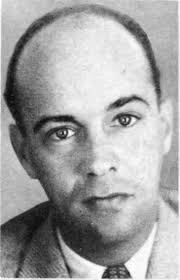

The first researcher to properly foreground the idea of different “Voynich hands” was the US WWII codebreaker Prescott Currier: he noted not only that there were different types of handwriting (which he called “Hand 1”, and “Hand 2”), but also different types of contents, to the point that he grudgingly dubbed them different ‘languages’ (e.g. “Currier A” and “Currier B”, though it should be born in mind that his angle on them was overtly statistical/cryptanalytical rather than linguistic).

Rene Zandbergen has long written about numerous issues that arise from Currier’s A/B insights, as well as with the limits of what you can conclude from them (e.g. here): generally, it is more sensible to talk of Herbal-A, Herbal-B, Pharma-A, Bio-B, etc, because the differences between A and B taper and lurch around rather than abruptly switch.

What emerges from this is a far more nuanced and subtle picture than, say, Gordon Rugg ever assumed, as evidenced in particular by Mary D’Imperio’s interesting paper on cluster analysis (declassified in 2002).

Hand 1 vs Hand 2

But the same kind of thing turns out to be true of Currier’s initial Hand 1 / Hand 2 dichotomy: for when you look a little more closely at the pages, you find that there could easily be several different hands in play.

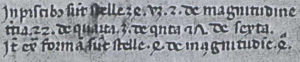

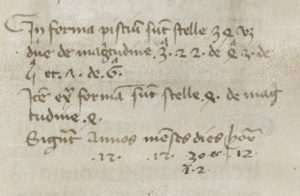

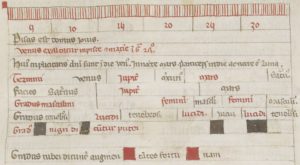

Certainly, few would disagree that there appears to be a broad division to be made between large-hand A pages (such as f8v, the last page of the first quire)…

…and tiny-hand B pages (such as f33r, the first page of Quire 5)…

It is certainly conceivable that Hand 1 and Hand 2 were both written by the same person (say, using different types of quill, or with different types of content, etc etc): moreover, some researchers (such as Sergi Ridaura and others) have specifically asserted that this is the case.

Yet the more that I have tried to work with the Voynich Manuscript’s pages as 15th century palaeographical artefacts, the less comfortable I have become with this suggestion. There are similarities between Hand 1 and Hand 2, for sure: but those similarities also sit at broadly the same kind of level you would expect to see from different scribes working in the same town, or taught by the same teacher. Further, I’d argue that there is no palaeographic ‘tell’ to be seen that links 1 with 2 in a definitive way: and that’s precisely the kind of thing you’d need to properly form the logical core of a “Hand 1 == Hand 2” argument.

More Than Two Hands?

Even though Currier started from this two-hand viewpoint (and was also not working with anywhere near as good a set of images as we now have), he eventually found himself pushed to a radical conclusion:

Summarizing, we have, in the herbal section, two “languages” which I call “Herbal A and B,” and in the pharmaceutical section, two large samples, one in one “language” and one in the other, but in new and different hands. Now the fact of different “languages” and different hands should encourage us to go on and try to discover whether there were in fact only two different hands, or whether there may have been more. A closer examination of many sections of the manuscript revealed to me that there were not only two different hands; there were, in fact, only two “languages,” but perhaps as many as eight or a dozen different identifiable hands. Some of these distinctions may be illusory, but in the majority of cases I feel that they are valid. Particularly in the pharmaceutical section, where the first ten folios are in a hand different from the middle six pages, I cannot say with any degree of confidence that the last ten pages are in fact in the same hand as the first ten.

Taken all together, it looks to me as if there were an absolute minimum of four different hands in the pharmaceutical section. I don’t know whether they are different than those two which I previously mentioned as being in the herbal section, but they are certainly different from each other. So there are either four or six hands altogether at this point. The final section of the manuscript contains only one folio which is obviously in a different hand than all the rest, and a count of the material in that one folio supports this; it is different, markedly different. I’m also positive it’s different from anything I had seen before. So now we have a total of something like five or six to seven or eight different identifiable hands in the manuscript. This gives us a total of two “languages” and six to eight scribes (copyists, encipherers, call them what you will).

So, might Captain Currier have been right about there having been so many contributing hands? Surprisingly, it’s not something that has been satisfactorily dealt with by palaeographers at any time in the last century. If you thought the silence following Mary D’Imperio’s paper was bad, the pin-drop-library-quiet surrounding Voynich palaeography is arguably even worse.

But perhaps we’ll start putting that right before too long…

Voynich Manuscript handwriting

Finally, the palaeographic problem with Voynich Manuscript handwriting is that it does not flow – for the most part, it’s not “joined-up writing”, as British children are taught to call cursive handwriting, but printed out, one letter (or short block of letters) at a time.

The reason I call this problematic is that this reduces our ability to do satisfactory palaeographical matching between Voynichese and other texts, simply because almost all other texts of the right kind of period are cursive. (So when we do comparisons between Voynichese and other texts, we are immediately at a disadvantage, because they are different kinds of things.)

The big exception to this sweeping generalization is, of course, humanist handwriting, which survives in numerous top-end Quattrocento examples much loved by palaeographers. While what we see in the Voynich Manuscript is most definitely not humanist handwriting, there is a strong case to be made that it is a “humanistic hand” – by which I mean something that borrows from the letter formation and ductus of both pure humanist hands and is yet close to more straightforward cursive mercantile hands of the time.

But a discussion of that will have to wait for a further post…