A few days ago, I tried using Fiverr.com‘s translation marketplace to enfrenchify the 598 words of my Kickstarter documentary pitch video. The required 10USD will only barely get you a round of drinks in a London pub: and yet given that this seemed to be the going rate for this size of work, I thought it would be an interesting exercise to get me some sous-titres.

All of which is a great theory, but how did it work out in practice?

The Mechanism

Fiverr.com does make it remarkably easy to order a translation: the person I chose turned out (according to his/her blurb) to be a native French speaker living in Morocco, which is absolutely fine by me.

However, I have to say that I found it hard to believe any of the brief biogs the fiverr.com translators put to their names / aliases. There was an air of polished nonsense to all of them, as though peeling back the virtual curtain would reveal a community of Nigerian scammer kiddies feeding your text into Google Translate and laughing at your compliant gullibility.

Of course, I know that’s not actually true or even remotely likely: but that was very much how it felt to me overall. So even though fiverr.com is technically quite sweet, I think it still struggles to make its vendors look credible. Doubtless others will disagree, but… I’m jus’ sayin’, is all. 😐

The Problems

Putting the core translation issue (i.e. of whether or not it’s any good) aside, the biggest problem turned out to be ‘sense reversal’. By which I mean: for the pitifully small amount of money involved, these online translators simply can’t afford to spend time deeply parsing your text, so there is a good chance that they will misread a given sentence and, as a result, accidentally flip its sense into the opposite of what you intended. This occurred three or four times (though these were all fairly easy to pick up), and I fixed them up by hand.

And so I’ve ended up with manually-fixed French subtitles based largely on the translation I bought.

Of course, what you are supposed to do when you find things wrong like that is to send them back for review, i.e. for you to flag such issues so that the translator can fix these problems for you (as part of the price). But I simply couldn’t bring myself to do that, for the simple reason that the amount of money involved was just too small: I felt too bad, if that makes sense.

Other people might possibly get around this feeling of guilt by asking for revisions and then giving a 10USD tip at the end (I wouldn’t be surprised if this is how it tends to work in practice). The only thing I did actually ask for was a single sentence early on that the translator had obviously translated but had accidentally cut-and-pasted over when putting the text together to send back, which I didn’t think was too big a request.

I don’t know: for all the good things about fiverr.com, I think that it is also a strange kind of low-end marketplace that can’t possibly give you technically tight text at the kind of prices quoted, simply because people can’t read text for the prices quoted, let alone translate it. And so I suspect that any kind of non-straightforward or strongly-logically-structured text may well end up being somewhat butchered, not out of intent but simply out of necessarily scant attention.

Perhaps all I can reasonably conclude about Fiverr is: Caveat Emptorr. 😐

Those French Subtitles In Full

As to whether it was worth it or not, here’s the translation.

Salut, mon nom est Nick Pelling.

Je dirige Cipher Mysteries, un blog des recherches historiques.

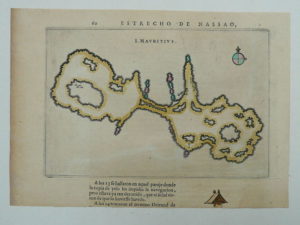

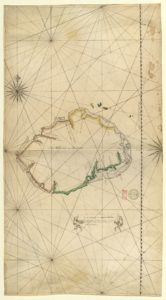

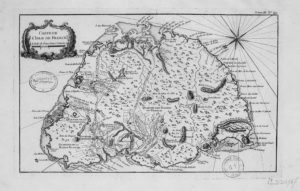

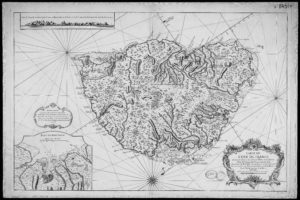

Ce que je tiens à couvrir sont les mystères historiques, quoi que ce soit avec des preuves douteuses à partir du manuscrit de Voynich jusqu’aux cartes aux trésors des pirates.

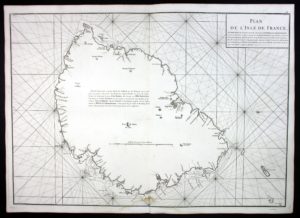

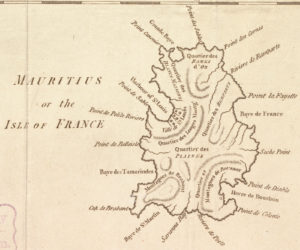

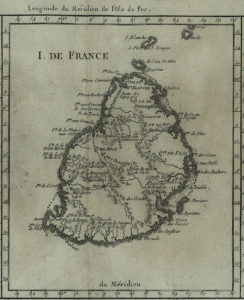

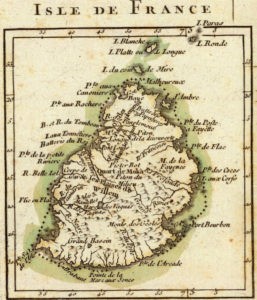

Et depuis des années, j’essayais de comprendre l’histoire d’un pirate de l’océan Indien qui porte le nom Bernardin Nagéon de l’Estang.

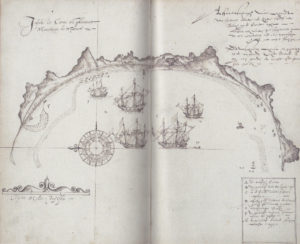

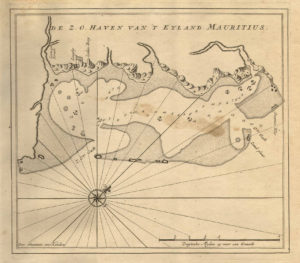

Il avait naufragé prétendument dans la côte Sud-Ouest de l’île Maurice, et il avait récupéré le trésor de son bateau ; il a repris un ruisseau par une falaise ; et puis il l’enterré dans une caverne souterraine qui avait été cachée par des pirates.

C’est une histoire incroyable, bien sûr, mais il faut être très prudent sur ce que vous croyez de ces mystères chiffrés.

D’une part, il n’y a aucune preuve que “Bernardin Nagéon de l’Estang” a jamais existé ; et ses lettres ?

Il n’y a encore aucune preuve que ce qui est mentionné dans ces lettres est vrai.

Tout ce que nous avons sont les différentes versions de ces lettres contradictoires qui confondent les uns des autres.

Pourtant, malgré ces problèmes profondément enracinés, ces documents ont aidé à alimenter une ruée vers l’or du pirate sur l’île Maurice.

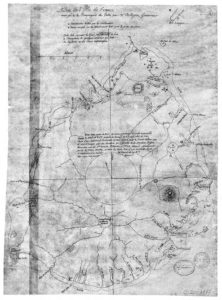

Pendant des années – voire des décennies – les mauriciens arpentaient autour de l’île, avec impatience la recherche de tout signe de trésor des pirates, les marques secrètes de pirate – plus précisément les lettres « BN », les initiales du pirate – creusées dans les rochers qui pourraient les conduire à ce cache fabuleux trésor, à l’or au-delà de vos rêves.

En fait, ce qui s’est apparemment passé est qu’aucun de ces chasseurs de trésor ait trouvé des choses comme une boucle d’oreille en laiton du trésor de Nageon de l’Estang… mais la question se pose encore – est-il encore là-bas ?

Ou sinon, pourrions-nous être en mesure de découvrir son histoire secrète, pour savoir ce qui lui est arrivé ?

Depuis quelques années, je l’ai lu et relu tout ce que je pouvais trouver sur Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang: et je pense que je peux enfin comprendre la plupart de ce qui est arrivé.

Mais je cherche maintenant à soulever mes recherches au niveau suivant, et aller à l’île Maurice elle-même, pour parvenir finalement en profondeur ce mystère.

Mais j’ai besoin de l’aide de Kickstarter … J’ai besoin de votre aide pour le faire.

Votre soutien ouvrira beaucoup de portes qui sont restées fermées pour moi.

En discutant avec les historiens et les chasseurs de trésor, en regardant les archives et les musées, en foulant le sol que Nagéon de l’Estang prétend qu’il a sous enterré son Trésor, je pense que nous pouvons enfin aller au fond de ce mystère.

Mais il y a une touche Hi-Tech.

Si Nagéon de l’Estang a enterré son trésor dans une caverne qui a existé pour toujours, la science va surement nous aider à trouver quelque chose.

Ainsi, une partie du plan du projet est de prendre un GPR loué (radar à pénétration de sol) à l’île Maurice,

pour pénetrer ce sol, et voir si nous pouvons voir ce qui est là-dessous, voir s’il y a une grotte à trouver.

L’objectif ultime du projet est de ne pas trouver un trésor physique (même si ça va être génial), mais plutôt de faire des recherches historiques difficiles en plein air, à la caméra, complètement transparent.

Je ne sais pas ce que je vais trouver ; je ne sais pas quelle histoire sera racontée ; mais je sais que c’est un voyage que quelqu’un doit faire, et une histoire que quelqu’un doit raconter- et je pense que c’est le moment d’agir.

À la fin, nous devrions avoir un documentaire qui raconte l’histoire d’un rêve partagé de l’or d’un pirate qui a repris tout un pays.

Mais que sera-t-il en fait cette histoire, les secrets d’elle, je ne sais pas – mais je veux savoir, et avec votre aide, nous pouvons tous le trouver. Merci beaucoup !