Want to know about Antonio Guayneri? As always, Step One is to open Thorndike’s “History of Magic & Experimental Science” Book IV, and go straight to the index. OK: “Guaineri, Antonio, Chap. XLVII”. Let’s go, boiz.

Thorndike largely contents himself with extracting the list of Guaineri’s (many) individual books from the 1481 editio princeps printed at Pavia, as per the copy he examined “in the E. C. Streeter collection at the New York Academy of Medicine”. As far as manuscript copies of the de balneis go, he lists only Turin 1200 (H-II-16; Pasini Lat. 533), 15th century (I think this is dated 1451, ref “V K 10”?).

We also know that Guayneri’s de balneis appears in Pavia MS Aldini 488 (f70v-f74r) [not available online], and BNF Nouv. Acq. Lat 211 [1469, accessible online, but only in black and white]. There’s a 1481 copy online here (which seems to have postdated the 1481 incunabulum). A manuscript copy appears in the 1553 Venetian Giunta print compilation of balneological books (probably the most accessible source), where the text seems very close to MS Aldini 488 (which is in turn very close to BNF Nouv Acq Lat 211).

Guayneri began working on his de balneis around 1435 (when he accompanied his patron to a thermal bath), and then completed it in 1439, according to this article (in Italian). Hence from my Voynichese perspective, I find this interesting because his de balneis is both broadly in the right date range, and short enough to match the general size of the Voynich’s Q13B.

Annoyingly, while Thorndike lists the chapter headings for Michele Savonarola’s book on thermal baths in one of his appendices, he doesn’t do the same for Guayneri’s de balneis (probably because of its brevity). So I’m going to have to summarise its contents the hard way (dash and darn it).

Regardless, the first thing I do is to try to find the earliest copy of any given text I can. So… can I track down the MS Torino 1200 mentioned by Thorndike?

MS Torino 1200 [1451]

According to a 1922 inventory of Italian manuscripts, the contents of MS Torino 1200 (H-II-16, Cod Cart Lat, sec XV, cc 141) are/were as follows (all in Latin):

- Marco Marsilio da S. Sofia. Receptae super I-IV. Avicennae de febribus.

- Calvis Paulus de Mudila. (Calvi Paolo da Modena). Liber de urinis.

- Guainerio, Antonio. De Balneis Aquensibus in Ducatu Montisferrati.

- Guainerio, Antonio. Tractatus de mulierum aegritudinibus.

- Bernerio Gerardo. Consultationes medicae.

- Petrus de Ebeno (Pietro d’Abano). Tractatus de venenis, eorumque medela.

- Gentili, Gentile. Tractatus de proportione medicinarum.

- Guainerio, Antonio. Tractatus de fluxibus.

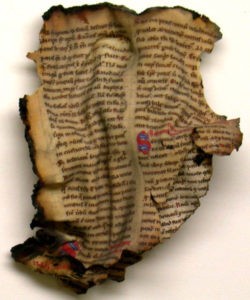

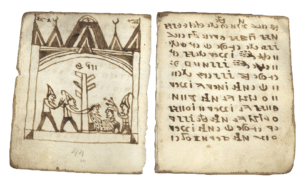

However, I can’t tell whether this manuscript was a victim of the infamous fire of 1904: though many mss were destroyed, many others were rescued or restored. (The Biblioteca was also bombed in 1942.) I found a picture of a similar Torino manuscript that had suffered fire damage in this (Italian) article:

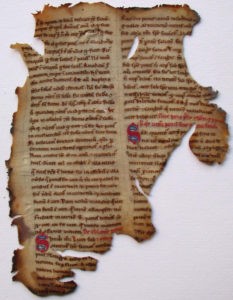

The silver lining from the 1904 Turin fire was the rapid increase in the specialist knowledge of how to restore badly damaged manuscripts. For example, the above fragment was restored to this state:

As an aside, there are some truly epic pictures showing the Italian restorers’ numerous tricks at the end of this other (Italian) article, which I highly recommend.

As an aside, the only Antonio Guayneri manuscripts I found in Italian library catalogues were:

- Milano, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Manoscritti, A 108 inf. (1474), which had just about everything else Guayneri wrote (but not his De balneis); and

- Modena, Biblioteca Estense – Universitaria, Estense, Lat. 607 = alfa.9.13, which only had his De calculosa passione.

I can only really assume (unless you know better?) that MS Torino 1200 was destroyed, probably in the 1942 bombing. So I’m instead going to work with BNF Nouv Acq Lat 211, which seems to be a 1469 copy of a 1454 copy.

BNF Nouv Acq Lat 211 [1469]

You might think that the smart transcription shortcut would be to grab a copy of the 1553 Giunta balneological compilation “De Balneis omnia quae extant” (fol. 43 ff.) and see how close that gets you. However, if you do, you’ll quickly find that the text has plenty of itty bitty Latin abbreviations while the OCR is far from perfect. And then you’ll find that there are plenty of places where the print version seems to have taken plenty of liberties with the text (presumably to make it more palatable to a print audience more than a century later). And the abbreviations are used in an entirely different way.

So rather than map this 16th century print rendering onto the 1469 manuscript copy, what I actually ended up doing was using the 1553 Giunta book to roughly guide me as I transcribed the 1469 manuscript (if that makes sense).

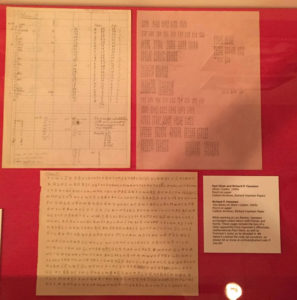

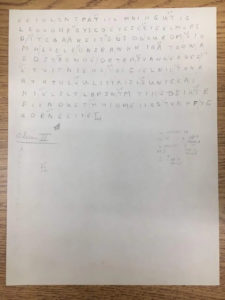

So, here’s a quick initial transcription (i.e. I haven’t corrected this at all) to give you a feeling of what we’re looking at here, in all its funky abbreviated glory. More to follow in other posts, particularly on the middle chapters:

ANTONII GUAYNERII PAPIENSIS DE BALNEIS AQUIS CIVITATIS

ANTIQUE QUE IN MARCHIONATU MONTISFERRATI SITA SU[N]T

TRACTATUS INCIPIT

Quia no[n]nulli viri doctissimi, quor[um]da[m] balneo[rum] i[n] Italia existe[n]tiu[m] virtutes desc[ri]pseru[n]t p[ro]p[ter] mirabiles ip[s]o[rum] effectus, h[ab]ita su[n]t adeo famosa, vt a re[m]otissimis p[ar]tib[us], caterua langue[n]tium dicti[ua] [con]fluat. Su[n]t ite[m] alia de q[ui]b[us] tum p[ro]p[ter] guerras, tum p[ro]p[ter] euenientes ta[m] febro[?] pestes, apud modernos nulla sc[ri]ptura rep[er]it[ur]. Et n[isi] sup[er] excelle[n]tis virtutes essent, de eis a[m]plius me[n]tio nulla fieret.

[*] Haec quoq[ue] que dixi tam virtuosa balnea, i[n] marchio[n]atu Mo[n]tisferrati i[n] mobilissimo olim aeque sane co[m]itatu, in simulatio vni[us] ciuitatis, que ab ip[s]is aq[ui]s cal[d]is nome[n] retinuit sita sunt.

[*] Ea enim Aqui ciuitas illi[us] antiquissimi co[m]ptat[us] caput e[st].

[*] Et q[uia] illie aqui calide i[n] numerabilib[us] eg[ritudini]bus s[u]b ueniebant, aque sane antiq[ui]tus vocaba[n]t[ur]. Et ad huc aq[ui] sane co[m]itat[us] dict[us] e[st]. Fuit hec qua[m] dixi ta[m] antiqua ciuitas, a, siluio p[ri]mo latino[rum] rege, [con]dita, vt ei[us] i[n] analib[orum] legi. Et quo et tu[n]c syluia dicta e[st].

[*] Post adue[n]tum vero [Christi], hi semp[er] fidelissimi fuere [christi]ani: sic vt [?]esis i[n] eis nu[n]q[uam] rep[er]ta sit. Cui[us] c[aus]a beat[us] papa siluester ep[iscop]alem sedem sibi [con]donauit. A quo deinceps syluestris dicta e[st].

[*] Ve[rum] totie[n]s hec misella ciuitas euersa e[st]: vt tam silie, q[uam] siluest[r]e, no[min]ibus abolitis, antiquu[m] solu[m] aq[ui]s retinuit nome[n]

[*] Que octi[n]gentos tam a[n]nos sub dictione sup[er]illustris [...]

[...]

Capitulu[m] [secundu]m. De balneo[rum] ext[ri]nseco[rum] notificatio[n]e, at que et qualis sit tam ext[ri]nseco[rum] qu[em] i[n]t[ri]nseco[rum] minera, quib[us] quoq[ue] i[n] generali eg[ri]tudinib[us] [con][uener?]unt.

[...]

Capitulu[m] [tertiu]m. Que si[n]t balneo[rum] p[re]sc[ri]pto[rum] p[ro]p[ri]etates

ac quibus p[ar]ticularibus eg[ri]tudinibus [con]ueniunt.

[...]

Capitulum [quartu]m. Qua[lit]er ta[m] balneis, q[uam] ceno, q[uam] stufa vti debe[amus],

& de modo bibendi aqua[m] fontis.

[...]

Capitulum [quintu]m. De mo[do] succurre[n]di, accidentib[us], q[uo] ex his balneis accidu[n]t, qn p[er]fectiora su[n]t. Et q[ua]ntu[m] sit tibi te[m]pus i[m]mora[n]du[m].

[...]

[*] Explicit tractatus pro balneis de aqu[ui]s. Editus p[er] claru[s] artui[?] et medicine doctore[m] magistru[m] Antoniu[m] de guaynariis papiensius

Finitus, die xxi maii, 1454, hora xvii. Laus deo.