The occasional gentle thunk sound of a book landing on my doormat has of late been replaced by a near-continuous clunking sound, as my second hand book addiction has changed gears. It feels like I now know just about everything anyone sensible would eer want to know about Unit 731, Fu-go balloons, the Roswell Incident, War in the Pacific, Project Helios, Project Mogul, Piccard family minutiae, etc etc. And still books keep arriving.

Anyway, here’s a brief 16x-speed scan of what I’ve been working my way through in the last few days.

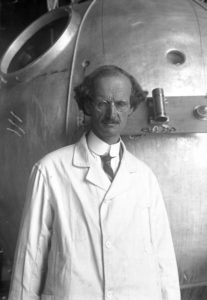

Jeannette Ridlon Piccard

I was very pleased to find a biography of Jean Felix Piccard’s wife Jeannette Ridlon Picard online. This was Sheryl K. Hill’s (2009) in-depth (and yet very readable) dissertation “ ‘Until I Have Won’ Vestiges of Coverture and the Invisibility of Women in the Twentieth Century: A Biography of Jeannette Ridlon Piccard“.

The central primary source that Hill relied upon was the The Piccard Family Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., that had been donated to the LOC by Jeannette Piccard, and which you may (possibly) recall being mentioned here previously.

And so it is that Hill seems to have read all the correspondence from all the boxes I was most interested in, which hopefully has saved me an awful lot of time and effort. 🙂

In the section “Stratospheric Flight Déjà vu: Helios Project” (pp. 249-252), Hill briefly tells the story of how Project Helios unwound (from Jeannette’s point of view) [p. 250]:

However, within months it was evident the Navy Department was taking over the project, now classified “confidential: project number 9-U-J,” and known as “Free Balloon Research Laboratory.” Part “B-1a” specified the contractor “shall design, construct, test and fly the stratosphere balloon specified in the contract with a crew approved by the Navy.” The December 1946 news release indicated the ONR had “entered into a contract with the General Mills Aeronautical Research Laboratory for the construction of a special cluster-type balloon and gondola to be used for scientific studies in the higher altitudes…The ascent itself [was] planned for mid-June [1947] from the Naval Air Station at Ottumwa, Iowa…” The news release indicated the “services” of Jean Piccard were “under contract,” but no mention was made of Jeannette’s role as pilot.

It didn’t take too long before the ONR pulled the money rug from under the whole project [p. 251]:

Although Jean remained optimistic that a clustered-balloon flight could be made, the

Navy pulled its financial support in June 1947, stating “operational tests of the prototype

balloons which were to be used in a cluster to form a lifting medium for project Helios

have clearly demonstrated that a piloted flight cannot be accomplished this year.” Jean

wrote his fellow scientific collaborators that he would do “all…possible…to organize a

stratosphere flight at the earliest possible date…” “I shall not leave you stranded,” he

stated, “but I shall make a serious effort to get other sponsorship.”

And that, as far as the Piccards seem to have been concerned with Project Helios, was that: despite their (literally) high hopes, they never did manage to reach the stratosphere together. For me, the #1 unanswered question was whether they secretly planned to inaugurate the 20-Mile High Club? Hill doesn’t say, so I guess we’ll never know.

Lt. Harris F. Smith USNR

So it seems that we are left with a small (but niggling) gap in the ballooning timeline between the end of Project Helios (June 1947) and the start of Project Skyhook (where the first balloon was launched on 25th September 1947). Note that there seems to be no record of “Project 9-U-J” anywhere: in NARA, just about everything with “9-U-J” turns out to be an OCR error. So for now I’m running with the idea that 9-U-J was just an internal ONR reference for Project Helios, rather than some other top secret project name.

According to Craig Ryan (The Pre-Astronauts, p.63), the ONR replaced Jeannette Piccard as pilot with “balloonist and airshipman Lt. Harris F. Smith USNR”. I’m pretty sure this is the same “Lt. Smith from Navy NYU” who arrived at Alamogordo on 28th June 1947, as noted in Albert Crary’s logbook, because this would help explain how the Project Mogul team moved from serial linkage between balloons to using a Project Helios (parallel) cluster mounting around this time:

Balloon expedition personnel arrived Saturday evening – Peoples, Trakowski, Mears, Ireland, Olsen, Moulton, Alden from AMS and Moore, Schneider, Hackman, Smith, Hazzard, 2 others and a Lt Smith from Navy NYU.

According to Fold3, Harris F. Smith had service number 4041150, and in 1942 was stationed at Lakehurst Naval Air Station, NJ. And according to the blurb for J. Gordon Vaeth’s (2005) “They Sailed The Skies” (my copy will arrive from America in a few weeks’ time, *sigh*), it was Harris F. Smith and William J. Gunther at Lakehurst who revived US Navy ballooning after WWII.

Because Ancestry’s account doesn’t include access to Fold3’s “Premium Features” (or indeed to Newspapers.com’s “Premium Features”), my best current guess is that this was Harris F. Smith born 4th September 1919 in Newark, NJ, died 26th Jan 2013 in New Jersey.

The 1947 Manned Balloon Incident

Now that I have a copy of Craig Ryan’s “The Pre-Astronauts”, I’m able to see the full text (and reference) for the 1947 manned balloon incident (pp. 20-21) I mentioned before:

One of the first postwar manned balloon flights sponsored by the military was launched from the Tularosa Basin in 1947 with the intent of crossing the Rockies and landing somewhere along the Eastern Seaboard. Unfortunately, the entire flight’s supply of ballast was expended in the crossing of the Sacramento range to the east of Alamogordo and the balloon’s journey ended just short of Roswell. A potential embarrassment, the aborted continental crossing was kept quiet and the pilot’s name never released. “We were naive as hell,” explained one of the NYU scientists.

Craig Ryan’s notes for this chapter gives the source of this story as an interview with Duke Gildenberg, who had worked in the NYU team in 1947, and then after graduation worked at Holloman AFB (which, prior to late 1947, was Alamogordo AAFB) from 1951 to 1981. Yet there are two curious things about this story. Firstly, the first manned polyethylene balloon flight on record was Charles B. Moore in 3rd November 1949 in Minneapolis. And secondly, even though Gildenberg was interviewed many times about the events of 1947 (four years before he started at Holloman), the interview with Gildenberg in Ryan’s book is the only place I’ve seen this incident mentioned anywhere.

Hence I’m currently trying to work out who that unfortunate balloonist was. It seems entirely possible that it was Lt. Harris F. Smith, but – as Gildenberg says – the flight was “a potential embarrassment”, and “was kept quiet”. So I’m guessing it will take a fair bit of work to retrieve it from the archival maw.

Note that this 1947 incident seems entirely separate from the 1959 incident with Dan D. Fulgham and Captain Joe Kittinger (“I also recall an incident involving a manned balloon flight.” etc) that Gildenberg gave testimony about decades later.

Earliest balloon launch date

According to this site, the first plastic balloon tests were on 24th April 1947:

This report describes the first outdoor inflation and flight attempt of a full-size pliofilm balloon on April 24, 1947. Purpose of the test was to obtain data on (1) proposed method of inflation; (2) use of plastic ground cover; (3) behavior of the aerostat at low wind velocity; (4) weighing off the aerostat; (5) rate of ascent; (6) operation of appendix; (7) excess lift for safe take-off without dragging; (5) balloon suspension system; (9) behavior of suspended parachute. Several preconceived opinions on these points were found wanting. A suspension harness failure precluded an actual flight. Nevertheless, the experiment was very revealing, producing information vital to any future attempt. Prior to the first outdoor inflation, a trial inflation had also been successfully made at the balloon loft.

The project update for Helios seems to imply that by May 1947, General Mills’ balloons were going well, though Piccard’s fancy high-altitude gondola-made-for-two was still very much a work in progress:

Between June 1946 and May 1947 the contractor has designed and built the gondola and auxiliary equipment for Helios to within 75% of completion, and has tested and built seven large, and several small balloons made of various plastic films. Through trial and error it has been shown that the present design will fly if the proper plastic film is used. The ideal balloon material has not yet been found, but an adequate plastic film, polyethylene, is now in production and 500 lbs. of this film will be available for assembling in June. A balloon which loses practically no lift in twelve hours has been developed. It has a diameter of 70 feet and a volume of 165,000 cubic feet. By stressing the cellophane-taped seams, it is possible to use a film of lower tensile strength and keep the weight of each cell below 100 pounds.

Presumably the “500lbs of this film [that] was available for assembling in June [1947]” went towards Project Mogul’s relatively small needs. Might the rest have been made into a separate balloon?

Interview with Gilruth

Finally, there’s a curious almost-an-out-take in an oral history interview with Robert Gilruth given by David DeVorkin:

GILRUTH: Yes, I remember that Piccard was very, very hurt by the National Geographic that would not give them a dime, and they gave so much to these other people. There was a colonel I can’t remember his name now —

DEVORKIN: Anderson, and a Major Kettener?

GILRUTH: No. There was one that lost his life or almost lost his life. I can’t remember those things anymore.

Which colonel was Gilruth was referring to here?