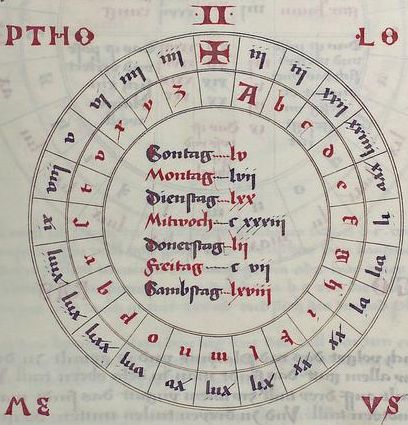

Following my recent post on modern per-degree astrology, Rene Zandbergen very kindly left a comment here pointing to online scans of a 15th century German translation of some of Pietro d’Abano’s works on astrology. While idly flicking through that, I noticed (starting on folio 132r) a short book by Johannes Hartlieb on ‘Namenmantik’ (onomancy, using names to tell fortunes). Dating right to the middle of the 15th century, this shows circular volvelle-like things that remind my eye of Alberti’s speculum (his rotating code wheel):-

Cod. Pal. germ. 832 Heidelberger Schicksalsbuch, folio 132r

Given that this kind of thing was in the air round that time, was it mere chance that Alberti happened to devise it first? It’s true that Hartlieb’s ones (like the one for Ptolemy above) probably didn’t rotate at all… but all the same, I do honestly think it wouldn’t have involved a vast leap of mid-Quattrocento imagination to make them do so.

But the mention of Hartlieb reminded me of another research strand I’ve been meaning to blog about – flying potions. You see, it was Hartlieb who first wrote (in 1456) about witches’ flying potions, in his puch aller verpoten kunst, ungelaubens und der zaubrey, i.e. on “forbidden arts, superstition and sorcery”.

Reading up again on this subject just now, I was somewhat disappointed to discover that Ioan Couliano’s colourful account of how the handles of broomsticks were used to administer the hallucinogenic unguent turns out to be only supported by a single (and fairly unreliable) source. Mainly, the ointment seems more likely to have been administered to the armpits and absorbed into the bloodstream from there. Still, it probably beats flying cattle class on a charter flight, right?

To me, the bizarre thing about the historical sequence is that in the early Middle Ages it was heretical to believe witches’ descriptions of flight (because they were clearly delusional), while during the Early Modern period it became heretical to disbelieve witches’ descriptions of flight (because they were clearly possessed by the Devil). So much for the continual march forward of knowledge! 😮

For much, much more on this fascinating subject, I heartily recommend Shantell Powell’s set of pages on flying potions. Enjoy!