I’ve had a few recent emails from historical code-breaker Tony Gaffney concerning the Voynich Manuscript, to say that he has been hard at work examining whether Voynichese might in fact be an example of an early Baconian biliteral cipher.

This is a method Francis Bacon invented of hiding messages inside other messages, by (say) choosing between two typefaces on a letter-by-letter basis – that is, steganographically hiding a binary message inside another message, one binary digit at a time. To squeeze in a 24-letter cryptographic alphabet, you’d need 5 bits (2^5 = 32), a bit like a fixed-length Morse code. Bacon proposed the following basic mapping:-

a AAAAA g AABBA n ABBAA t BAABA b AAAAB h AABBB o ABBAB u/v BAABB c AAABA i/j ABAAA p ABBBA w BABAA d AAABB k ABAAB q ABBBB x BABAB e AABAA l ABABA r BAAAA y BABBA f AABAB m ABABB s BAAAB z BABBB

Immediately, it should be obvious that this is (a) boring to encipher, (b) awkward to typeset and proof, (c) boring to decipher, and (d) it requires a printed covertext five times the size of the ciphertext. So… while this would be just about OK for someone publishing prolix prose into which they would like to add some kind of hidden message for posterity, it’s not honestly very practical for “MEET ME BY THE RIVER AT MIDNIGHT”. Here’s a simple example of what it would look like in action (though using cAmElCaSe rather than Times/Arial, I’m not that sadistic):-

to Be, OR noT To be: ThaT is ThE quesTIon:

whETher ‘tiS nOBleR in the Mind tO SuffeR

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

[…]

Famously, the giants of ‘enigmatology’ (David Kahn’s somewhat derisive term for hallucinative Baconian Shakespeare-ology) Ignatius Donnelly and Elizabeth Wells Gallup hunted hard for biliteral ciphers in the earliest printed editions of Shakespeare, but I’m pretty sure there’s more in the preceding paragraph than they ever found. 🙂

Historically, Bacon claimed to have invented this technique as a youth in Paris (which would have been circa 1576), so it is just about possible (if you half-close your eyes when you look at, say, the fifteenth century marginalia, and squint like mad) that he (or someone to whom he showed his biliteral cipher) might have used it to encipher the Voynich Manuscript around that time. But that leads on to two questions:

- How might the stream of enciphered bits be hidden inside Voynichese?

- How could we decipher it reliably?

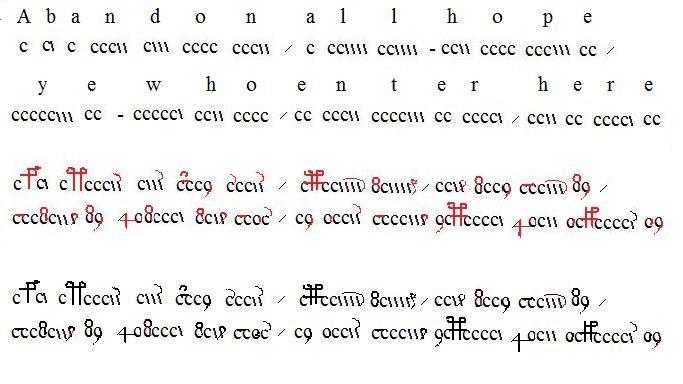

Tony’s suggestion is that Voynichese might be hiding “dots” and “dashes” (basically, binary zeroes and ones) in the form of ‘c’-like and ‘\’-like strokes (and where gallows are nulls and/or word delimiters), something along the lines of this:-

Spookily, back in 1992, Jim Reeds tried converting all the letters (apart from gallows) to c’s and i’s, to see if anything interesting emerged:-

Spookily, back in 1992, Jim Reeds tried converting all the letters (apart from gallows) to c’s and i’s, to see if anything interesting emerged:-

Starting with the original D’Imperio transcription, I converted some characters to ‘c’ and some others to ‘i’, and then counted letter pairs (for pairs of adjacent non space chars, viz, in the same word).

letters mapped to c: QWXY9CSZ826

letters mapped to i: DINMEGHRJKThe results, sorted by decreasing frequency:

15481 cc

4774 Ai

4375 Oi *** O like A on right

3612 cO *** O like A on left

2591 cA

2528 OF

2482 4O

2449 Fc

1496 Pc

1427 OP

1390 ic *** rule breakers

1313 Oc

1212 FA

690 cF

495 PA

455 iO

452 cP

362 Bc

359 FO

354 PO

330 iF

275 iA *** rule breakers

168 OB

164 ci *** a few more rule breakers

124 AT

102 Vc

89 cB

88 OA

87 BO

71 Ac

68 ii

54 OV

…From which one sees that O is as much c-like on the left and I-like on the right as A is.

Also notice that ic and ci does occur. In the B corpus, I-like letters seem to occur only at the ends of words. Typically a word starts out C-like and ends up I-like.

Can this I-like, C-like, and neutral stuff be a cryptological not linguistic phenomenon? Maybe the author has a basic alphabet where each letter has both a C-form and an I-form. He writes out the text in basic letters, and then writes the Voynich MS, drifting in and out of the C and I forms, just to amuse us. If this were the case, we should treat Currier <2> and Currier <R> as the same, etc, etc.

Or the author could be putting all the info in the choice of C-form versus I-form: C-form could be ‘dot’, and I-form could be ‘dash’, and choice of ‘base letter’ is noise. (Say, only the C/I value of a letter following a gallows counted, or maybe that and plume-presence of letter following a gallows.) That gives you a sequence of bits or of ‘dibits’, which is used in a Baconian biliteral or Trithemian triliteral cipher, say.

Or if you figure each word starts C-like and ends I-like, maybe the only signficant thing is what happens at the transition, which will take the form cAi or cOi. The significant thing is the pair of ci letters.

On rereading this all, it seems unlikely.

Could the VMs really be built on some kind of c-and-\ biliteral cipher? Cryptologically, I’d say that the answer is almost certainly no: the problem is simply that the ‘\’ strokes are far too structured. Though Tony’s “abandon all hope” demo shows how this might possibly work, his example is already both too nuanced (with different length cipher tokens, somewhat like Morse code but several centuries too early) and too far away from Voynichese to be practical.

While I would definitely agree that Voynichese is based in part around a verbose cipher (as opposed to what Wilkins [below] calls “secret writing by equall letters”), I really do doubt that it is as flabbily verbose as the biliteral cipher (and with lots of delimiters / nulls thrown in, too). I’d guess that a typical Herbal A page would contain roughly 30-40 characters’ worth of biliteral information – and what kind of secret would be that small?

As an historical sidenote, Glen Claston discussed the biliteral cipher on-list back in 2005:-

[…] I’ll clue you in to Bacon research – only two books are of interest, both post-fall for Lord Bacon. (I own originals of all of them, so I’m positive about this). The biliteral cipher exists in only two books, the first of which is the Latin version “De Augmentis”, London edition, 1623. This will lead you to the second, published “overseas”. (No real ground-breaking secrets there however). It raises its head only one other time, in a book entitled “Mercury, the Swift and Secret Messenger”. (Only two pages here, at the beginning, a simple exercise). [A brief use in a Rosicrucian manuscript, but Bacon was not a Rosicrucian, so this is simple plagiarism].

To be accurate, John Wilkins’ 1641 “Mercury, the Swift and Secret Messenger” does actually devote most of its Chapter IX to triliteral and biliteral ciphers (which he also calls “writing by a double alphabet”), with a reference in the margin specifically pointing to Bacon’s “De Augmentis” as its source. Personally, I suspect that Wilkins was having more fun with…

Fildy, fagodur wyndeeldrare discogure rantibrad

…though I suspect a “purer” version of the same would be…

Fildy, fagodur wyndeldra rogered ifsec ogure rantebrad

Read, decipher, enjoy! 🙂