[Here are links to chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Enjoy!]

* * * * * * *

Chapter 3 – “Unjust Desserts”

“I suppose you just happened to pick this up at a rummage sale?”, said Emm, minutely scrutinizing the jacket’s material through her Swiss army knife’s magnifying glass.

“No, it was my grandfather’s – Mani Harvitz, he was a WWI codebreaker. He knew John Manly well, so must have known all about the Voynich Manuscript, I guess.”

“Hmmm… so why’s it in such good condition?”

“Ah”, said Graydon as he leaned over to pick up his club sandwich, “there’s a family story. On the boat back to the US from some European trip in the late 1920s, my grandpa fell seriously ill – and that turned out to be the tail end of the whole encephalitis lethargica epidemic.”

“Oh my God”, said Emm appalled, “the whole Oliver Sacks ‘Awakenings‘ thing, right?”

“Right. My grandfather stayed in a kind of catatonic state for decades – he died before I was born. Somehow I ended up inheriting his favourite jacket.”

Emm paused, looking at him through narrowed eyes, furious mental calculations plainly rattling through her head. The moment she turned her magnified gaze around to the small piece of parchment. Graydon stuffed an ungraciously large lump of sandwich into his mouth, trying hard not to moan with pleasure at his accelerated relief from starvation.

“Well, at least we know what he was doing”, Emm said, her shoulders relaxing a little as she began to take off her white cotton gloves.

“Errrm… which was… what?” Graydon replied, trying hard not to open his overfilled mouth too widely.

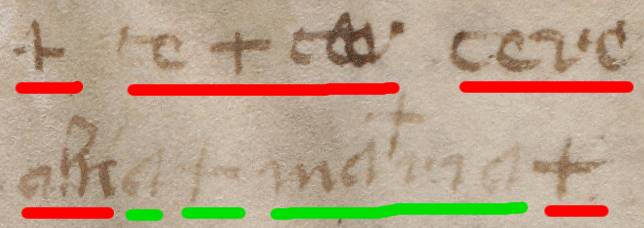

“For a start, he was visiting the Knihovna národního muzea v Praze – the Czech National Library, you can tell from the handwritten shelfmark. And here’s the giveaway he was stealing this”, she continued, pointing at the vellum’s left hand side , “the clean edge where Mani cut it out – probably with a smuggled-in razor blade – before stashing it in his secret pocket.”

“Jeez, so now I’m on a lunch date with Gil Grissom. Did you happen to notice any anomalous beetle larvae?”

“You ate your sandwich first, you tell me. Was the salad unusually… crunchy?”

But now it was Graydon’s turn to go vague and starry-eyed, triggered by a cascade of half-memories from his capacious mental warehouse of Voynich trivia. “I reckon the connection here is… Edith Rickert. See, my grandpa had had this massive crush on her from the codebreaking office, but she was utterly devoted to working with John Manly and so turned him down: basically, Mani got married on the rebound. I went through Rickert’s letters in the archives: the last one from him promised to travel up and show her something she’d be very interested in. Didn’t say what it was, though.”

“So, if Edith Rickert was into the Voynich…”

“Way back then, Wilfrid Voynich called it his ‘Roger Bacon Manuscript’, but I don’t think she was ever fooled.”

“OK, whatever the damn manuscript was called, it seems pretty likely to me that the thing hidden in this jacket was a Voynich-related fragment your grandpa stole from the Czech museum library to try to impress Rickert.” Emm said as she finally reached over to her plate. “You know, exciting her mind to get her into bed.”

“People do recommend that, but honestly, it’s never worked for me yet”, said Graydon. “Personally, I tend to find a nice lunch far more effective.”

Emm laughed, nearly choking on her sandwich, before frowning and pointing an accusatory finger at him. “Don’t you get any ideas – it would take much more than a club sandwich to get me into bed.”

“Whatever you say, Scully. Oh, the desserts here are pretty good, by the way.”

“Cheeky bastard!”

“And you’d definitely have to promise not to wear those cotton gloves”, continued Graydon grinning. “That would be wrong on so many levels.”

“Well, as long as I get to keep my magnifying glass and ruler, though.”

“Cheeky bastard!”

They both paused awkwardly, eyes scanning the other, resolutely reading between each other’s lines.

“Look”, said Emm as she began putting her things back into her clutch bag, “I’ve… I’ve got to get back to work now, before Mrs Kurtz starts punching the film crew. Could turn ugly.”

“That’s good”, said Graydon, noticing that even he didn’t believe the sound of his own words. “Ummm… thanks for dismantling my jacket and giving me a whole new research lead. Might even save my PhD. Oh, and I’d be very happy to help you with your cleaning, any time.”

“That’s great”, she replied, but her face was looking away as she stood up to leave. “Anyway, the Voynich film crew are filming an interview with Marina Lyonne this afternoon, I guess you probably know her, right?”

Graydon’s face dropped faster than a Wile E. Coyote grand piano. “Yeah, I know her”.

Ouch-a-rama.

His Voynich über-skeptic ex-wife was in town.

Oh, Marina, Marina, Marina: she knew the Beinecke curators very well – far too well, in fact – and she had a score of scores to settle with him. And this was more than just a bad moment for her to turn up wielding her +10 Axe of Grudgery, this was surely the worst imaginable moment.

Whoever said “one step forward, two steps back” was surely wearing X-ray specs, looking at the workings of the heart…

John Matthews Manly and Edith Rickert, 1932

John Matthews Manly and Edith Rickert, 1932