I recently stumbled across a forum discussion comparing the Voynich Manuscript to the “Maybrick Diary” (oh, and the Vinland Map, too) inasmuch as they are all high profile documents that have been dubbed fakes or hoaxes. James Maybrick was a Victorian cotton merchant from Liverpool high up the ludicrously long list of people variously accused of being Jack the Ripper, as well as the alleged author of a Ripperesque diary that surfaced in 1992.

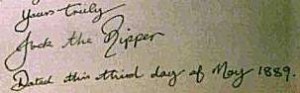

It seems that just about everybody (apart from Robert Smith, the present owner) is reasonably sure that the Maybrick Diary (written in a Victorian diary with the first 20 pages ripped out) is a fake: Michael Barrett, who originally claimed to have bought it in a pub, later swore (twice) that he had dictated the diary to his wife, though these affadavits were (apparently) subsequently repudiated.

To me, the Maybrick Diary fits the general template of hoaxers falling out after the event, guiltily unable to keep up the pretence, not unlike the mad furore over the fake alien autopsy I described a while back. In pattern-speak, one might observe that a Beneficiary (Michael Barrett / Ray Santilli) benefits from the appearance of a MacGuffin (the Maybrick Diary / alien autopsy footage) claiming to unravel a notorious unexplained Mystery (Jack the Ripper / Roswell), but couldn’t quite keep up the pretense for a long time.

Compare that with the Vinland Map, and you can see why historians like Kirsten Seaver go looking for that person who benefitted from its appearance: for without a Beneficiary, you haven’t really got a hoax. Seaver proposed that the VM was forged by an Austrian called Josef Fischer (1858-1944) after about 1923, for a rather tortuous (dare I say “Jesuitical“?) reason involving teasing unknown Nazi scholars. However, introducing Nazis (particularly without any actual evidence) is normally a sign that you’ve lost the argument: so it’s easy to understand why Seaver’s otherwise intensely detailed research has failed to please. What everyone does now agree is that it is an astonishingly clever object, whichever century (or centuries) it was from.

And what of the Voynich Manuscript? While some unknown person did benefit (to the tune of 600 ducats) from its first half-documented appearance in Prague, you’d have to imagine really hard (to the point of hallucination) that they actually created it as well – the VMs has a complex, multi-layered codicology that speaks of a busy 15th century existence in the hands of multiple owners, a whole century before Rudolf II’s collecting heyday. Oh, and the other problem with seeing the VMs as a hoax is that it is doesn’t claim to unravel a Mystery – it is itself the Mystery. Unless you can imagine something even more mysterious?