It’s been a rollercoaster of a day for me at the Warburg Institute on the Early Modern Research Techniques course, like being given the keys to the world twice but having them taken away three times. I’ll try to explain…

Paul Taylor kicked Day Two’s morning off in fine style, picking up the baton from Francois Quiviger’s drily laconic Day One introduction to all things Warburgian. My first epiphany of the day came on the stairs going up to the Photographic Collection: an aside from Paul (that the institute was “built by a madman”) helped complete a Gestalt that had long been forming in my mind. What I realised was that even though the Warburg’s “Mnemosyne” conceptual arrangement was elegant and useful for a certain kind of inverted historical study, it was actually pathological to that entire mindset. Essentially, it seems to me that you have to be the “right kind of mad” to get 100% from the Warburg: and then you get 100% of what?

(The Warburg Institute is physically laid out unlike any other library: within its grand plan, everything is arranged neither by author, nor by period, nor by anything so useful as an academic discipline, but rather by an arbitrary conceptual scheme evolved to make similar-feeling books sit near each other. It’s not unlike a dating service for obscure German publications, to make sure they keep each other company in their old age.)

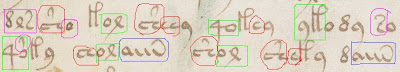

My second epiphany arrived not long afterwards. On previous visits, I’d walked straight past the Warburg Photographic Collection, taking its darkness to mean that it was closed or inaccessible: but what a store of treasures it has! My eyes widened like saucers at all the filing cabinets full of photographs of astrological manuscripts. I suddenly felt like I had seen a twin vision of hell and purgatory at the core of the Warburg dream – both its madness and its hopefulness – but had simultaneously been given the wisdom to choose between them.

It was all going so well… until Charles Hope (the Warburg’s director) stepped forward. Now: here was an A* straight-talking Renaissance art historian, sitting close to the beating heart of the whole historical project, who (Paul Taylor assured us) would tell it like it is. But Hope’s message was both persuasive and starkly cynical: that, right from the start, Aby Warburg had got it all wrong. And that even Erwin Panofsky, for all his undeniable erudition, had (by relying on Cesare Ripa’s largely made-up allegorical figures) got pre-1600 iconology wrong too. With only a tiny handful of exceptions, Hope asserted that Renaissance art was eye candy, artful confectionery whipped up not from subtle & learned Latin textual readings (as Warburg believed), but instead from contemporary (and often misleading and false) vulgar translations and interpretations – Valerius Maximus, Conti, Cartari, etc. And so the whole Warburgian art history research programme – basically, studying Neoplatonist ideas of antiquity cunningly embedded in Renaissance works of art – was dead in the water.

To Hope, the past century of interpretative art history formed nothing more than a gigantic house of blank cards, with each card barely capable of supporting its neighbours, but not of carrying any real intellectual weight on top: not unlike Baconian cryptography (which David Kahn calls “enigmatology”). All of which I (unsurprisingly) found deeply ironic, what with Warburg himself and his beloved Institute both being taken apart by the Warburg’s director.

The second step backwards came when I tried to renew my Warburg Institute Reader’s Card: you’re not on the list, you can’t come in. (Curiously, there were already two “Nicholas Pelling“s on their computer system, neither of them me.) It seems that, without direct academic or library affiliation, I’m now unlikely to be allowed access except via special pleading. Please, pleeeease, pleeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeease… (hmmm, doesn’t seem to be working, must plead harder). If I had a spare £680 per year, I’d perhaps become an “occasional student” (but I don’t).

My third (and final) step backwards of the day was when I raced up to the Photographic Collection both during the afternoon tea-break and after the final lecture and had an Internet-speed finger-browse through the astrological images filing cabinets. Though in 20 minutes I saw more primary source material than I would see in a fortnight at the British Library, I ended up disappointed overall. Yes, I saw tiny pictures of a couple of manuscripts I had planned to examine in person next month (which was fantastic): but there didn’t seem to be anything else I wasn’t already aware of. Rembrandt Duits has recently catalogued these mss in a database (though only on his PC at the moment), so perhaps I’ll ask him to do a search for me at a later date…

Perhaps I’m wrong, but it seemed to me that even though old Warburgian/iconological art history is basically dead, the new art history coming through to replace it revolves around precisely the kind of joint textual and stylistic interpretation I’m doing with the Voynich Manuscript, with one eye on the visual sources, and the other on the contemporary textual sources. Yet the problem with this approach is that you have to be an all-rounder, a real uomo universale not to be fooled by spurious (yet critical) aspects along the way. All the same, though I’m no more than an OK historian (and certainly not a brilliant one), I’m now really convinced that I’m looking at a genuinely open question, and that I’m pointing in the right kind of direction to answer it.

Don’t get me wrong, Day Two was brilliant as a series of insightful lectures on the limits and origins of art historical knowledge: but I can’t help but feel that I’ve personally lost something along the way. Yet perhaps my idea of the Warburg was no more than a phantasm, a wishful methodology for plugging into the “strange attractors” beneath the surface of historical fact that turned out to be simply an illusion /delusion: and so all I’ve actually lost is an illusion. Oh well: better to have confident falsity than false confidence, eh?

As a curious aside, for me this whole historical angle on the Warburg also casts a raking light across the “Da Vinci Code”. The book’s main character (Robert Langdon) is a “symbologist”, a made-up word Dan Brown uses to mean “iconologist”: and as such is painted on the raw canvas of the Warburg ‘project’. What cultural archetype is the ultra-erudite, friendly (yet intellectually terrifying) Langdon based upon? A kind of Harvardian Erwin Panofsky? In my mind, the “Da Vinci Code” (and its ‘non-fiction’ forerunner, “Holy Blood, Holy Grail”) both sit astride the ebbing Warburg wave, both whipping at the fading waters: and so the surge of me-too “The [insert marketing keyword here] Code” faux-iconology books and novels is surely Aby Warburg’s last hurrah, wouldn’t you say?

R.I.P. 20th Century Art History: now wash your hands. 🙁