For decades, Voynich Manuscript research has languished in an all-too-familiar ocean of maybes, all of them swelling and fading with the tides of fashion. But now, thanks to the cooperation between the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library and the documentary makers at Austrian pro omnia films gmbh, we have for the very first time a basic forensic framework for what the Voynich Manuscript actually is, vis-à-vis:-

- The four pieces of vellum they had tested (at the University of Arizona / Tucson) all dated to 1420-1, or (to be precise) 1404-1438 with 95% confidence (“two sigma”).

- The ink samples that were tested (by McCrone Associates, Inc.) were consistent with having been written onto fresh vellum (rather than being later additions), with the exception of the “cipher key” attempt on f1r which (consistent with its 16th century palaeography) came out as a 16th-17th century addition.

- It seems highly likely, therefore, that the Voynich Manuscript is a genuine object (as opposed to some unspecified kind of hoax, fake or sham on old vellum).

The f1r cipher “key” now proven to have been added in the 16th/17th century

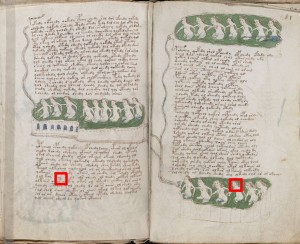

The programme-makers conclude (from the ‘Ghibelline’ swallow-tail merlons on the nine-rosette page’s “castle”, which you can see clearly in the green Cipher Mysteries banner above!) that the VMs probably came from Northern Italy… but as you know, it’s art history proofs’ pliability that makes Voynich Theories so deliciously gelatinous, let’s say.

Anyway… with all this in mind, what is the real state of play for Voynich research as of now?

Firstly, striking through most of the list of Voynich theories, it seems that we can bid a fond farewell to:

- Dee & Kelley as hoaxers (yes, Dee might have owned it… but he didn’t make it)

- Both Roger Bacon (far too early) and Francis Bacon (far too late)

- Knights Templars (far too early) and Rosicrucians (far too late)

- Post-Columbus dating, such as Leonell Strong’s Anthony Askham theory (sorry, GC)

It also seems that my own favoured candidate Antonio Averlino (“Filarete”) is out of the running (at least, in his misadventures in Sforza Milan 1450-1465), though admittedly by only a whisker (radiocarbon-wise, that is).

In the short term, the interesting part will be examining how this dating stacks up with other classes of evidence, such as palaeography, codicology, art history, and cryptography:-

- My identification of the nine-rosette castle as the Castello Sforzesco is now a bit suspect, because prior to 1451 it didn’t have swallowtail merlons (though it should be said that it’s not yet known whether the nine-rosette page itself was dated).

- The geometric patterns on the VMs’ zodiac “barrels” seem consistent with early Islamic-inspired maiolica – but are there any known examples from before 1450?

- The “feet” on some of the pharmacological “jars” seem more likely to be from the end of the 15th century than from its start – so what is going on there?

- The dot pattern on the (apparent) glassware in the pharma section seems to be a post-1450 Murano design motif – so what is going on there?

- The shared “4o” token that also appears in the Urbino and Sforza Milan cipher ledgers – might Voynichese have somehow been (closer to) the source for these, rather than a development out of them?

- When did the “humanist hand” first appear, and what is the relationship between that and the VMs’ script?

- Why have all the “nymph” clothing & hairstyle comparisons pointed to the end of the fifteenth century rather than to the beginning?

Longer-term, I have every confidence that the majority of long-standing Voynich researchers will treat this as a statistical glitch against their own pet theory, i.e. yet another non-fitting piece of evidence to explain away – for example, it’s true that dating is never 100% certain. But if so, more fool them: hopefully, this will instead give properly open-minded researchers the opportunity to enter the field and write some crackingly good papers. There is still much to be learnt about the VMs, I’m sure.

As for me, I’m going to be carefully revisiting the art history evidence that gave me such confidence in a 1450-1470 dating, to try to understand why it is that the art history and the radiocarbon dating disagree. History is a strange thing: even though thirty years isn’t much in the big scheme of things, fashions and ideas change with each year, which is what gives both art history and intellectual history their traction on time. So why didn’t that work here?

Anyway, my heartiest congratulations go out to Andreas Sulzer and his team for taking the time and effort to get the science and history right for their “DAS VOYNICH-RÄTSEL” documentary, which I very much look forward to seeing on the Austrian channel ORF2 on Monday 10th December 2009!

UPDATE: see the follow-up post “Was Vellum Stored Flat, Folded, or Cut?” for more discussion on what the dating means for Voynich research going forward…