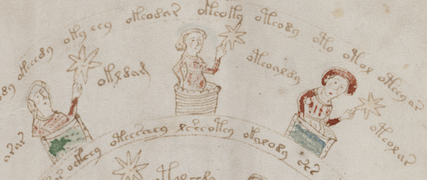

I’ve spent some time recently revisiting the Voynich Manuscript’s labelese, as well as its Pisces zodiac roundel page, and thinking about how that might relate to February. However, making all of these parallel strands “land” at the same time has proved difficult: even if the zodiac labels are some kind of cisiojanus “syllable soup”, we still have many practical problems linking everything together into one solid decryption.

Still, having now spent some time putting February’s “Bri pur bla sus” saint’s days and festivals under the microscope, it’s becoming apparent that many of these Christian saints were martyred virgins: and so perhaps the whole notion of oddly-angelic naked nymphs isn’t as far away from the subject matter as you might at first think.

Moreover, having thought about the really important feast days associated with men, I’m coming round to the idea that perhaps these may be connected to the few “male nymphs”. I’m thinking specifically about whether the beardy breastless nymph below might be connected with February 22nd, Cathedra Petri [the Feast of St Peter’s Seat].

So I’m now coming round to wonder: if the (relatively few) male nymphs in the zodiac section are broadly linked to specifically male feast days, might we be able to use them to reconstruct the nymph numbering? (i.e. which nymph is linked with which day.)

But before launching into that, I thought it would be good to see what people had previously posted on this general topic.

Notes on Nymph Numbering

D’Imperio mentions (3.3.3) that Peterson noted that some of the nymphs might be male: but doesn’t seem to mention trying to reconstruct the correct order of the nymphs.

Going through the voynich.net archives reveals various observations:

- Rene Z [15 Aug 1997]: “The nymphs were drawn from the inside ring outwards, with the text added either immediately or afterwards. I think there are two possibilities for the order: either starting near 00:00 and going clockwise or starting near 09:00 and going against the clock, this from observing where the nymphs are more cramped together (especially the inner circle of Sagittarius).”

- Rene Z [15 Aug 1997] “There is one nymph in Gemini without a label. I would favour the idea that this was a simple oversight. There is also one nymph without a star somewhere…”

- John Grove [05 Oct 1997]: “In the June and December pages, the first nymph outside the circle has a ‘carpet’ under her feet. If you read the calendar from the inside out (as I have had a tendancy to do), these two nymphs occur 5 (for June) and 4 (for December) — days? — before the end of the zodiac month.”

- Rene Z [1 Oct 1998]: “In the zodiac section, the standing nymphs all have their right hands either pointing backwards or placed on their hips.”

- Rene Z [18 Jan 1999]: “About 1 out of 6 of the standing nymphs have their hand pointing behind them, not on the hip. But for nine-pointed stars this fraction is zero. I checked that the probability of this is 0.02 if this was just due to chance.”

One thread also suggested looking here at a woodcut in: Paul Heitz (Hg.), Einblattdrucke des 15. Jh., Bd. 18: Richard Schmidbauer, Einzel-Formschnitte des 15. Jh. in der Staats-, Kreis- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg, Straßburg 1909, Taf. 9. Wilhelm Ludwig Schreiber, Handbuch der Holz- und Metallschnitte des XV. Jh., Leipzig 1925-1930, Nr. 1883a. However, Google Books didn’t seem to have a copy of this, alas.

I also found a VoynichViews blog post that highlighted a specific Sagittarius nymph holding her star downwards.

Please feel free to point me towards any posts that specifically discuss issues around determining / reconstructing the correct order of the Voynich zodiac nymphs, because (for example) I had no luck finding anything on voynich.ninja.

However, most of the interesting thoughts on the (old) list were in a single 1999 post by Jorge Stolfi: he wondered if he could discern any visual clues that signalled which was the first nymph of each zodiac page. So I decided to copy the whole post here as a section in its own right…

Jorge Stolfi’s thoughts [21 Jan 1999]

(Here’s what Jorge Stolfi posted on the subject of nymph numbering back in 1999):

Yesterday I thought that those nymphs might mark the starting point

for reading each ring of stars. Now that I have looked at those cases

with some care I am not so sure. Anyway, here are the cases that I

could see:

70v2 Pisces

There is one nymph with both arms raised at 00:15 in

the inner band.

I would say that this is the most likely starting point for

the inner star sequence, which runs clockwise (agreeing with

the text). Thus I think that the inner parade begins with

Miss Otalar (stretched arm), and ends with Miss Otaral

(facing clockwise)

This is another anomaly of Pisces, since in the

other diagrams the starting point seems to be around 10:30. I

suppose tha the last nymph at 11:30 was reversed so that it

would face the "honor spot" at noon.

The starting point of the outer band is not so obvious. I

would say it is near the top, too, but it could be before,

after, or in the middle of the four "baby" nymphs.f70v1 Aries “dark”

Here all nymphs have the right hand on the hip; several have

the left hand down too. My guess for the starting point is at

10:30 in both bands, i.e. Miss Otalchy (the Tar Am Dy) and

Miss Okoly. Note that they (and only they) are holding their

high enough to intrude into the surrounding text ring.

Moreover Miss Okoly is wearing a striped sleeve (or

whatever).

Note again that the label at 06:00 is not obviously

associated with any star, so it must be attached to one of

the nymphs. I would say that, going clockwise, each label is

associated with the preceding nymph.f71r Aries light

Here all nymphs have the same pose: right arm

on the hip, left arm up and holding the star.

The stars have no tails, except for the outer 04:30

one that has a very short one.

The starting point for each text ring is clearly marked by

the "notched square" device, which occurs in other cosmo

diagrams, presumably with the same function.

As I argued in my previous message, this is the zodiac page

with the most "primitive" style.f71v Taurus “light”

Here too all nymphs have the same pose. I see no obvious

"start" marker for the nymphs, except perhaps for the

decorated dustbin of Miss Otalody, the inner nymph at 00:00.

However the outer text ring has a wider gap at 10:30 (the

"standard" starting place), with a centered dot which may be

the last vestige of the notched square symbol.

To my eyes, the style of this page is only a bit less primitive than that

of f71r.f72r1 Taurus “dark”

The outer nymph at 02:30 has her right arm stretched back and

down; all the others have the right hand on the hip or inside

the dustbins.

There are no obviosu start markers that I can see, but the

reproduction I have is unreadable around 03:00. There is

anextra wide gap in the inner parade around 10:30, but that

may be a consequence of the "cigarette hole" and its visual

pun. Other plausible candidates are the nymphs at 00:00, Miss

Otchoshy and Miss Oaiin Ar-Ary.

I would say that the figures on the outer band of this

diagram are the first attempts by the artist at drawing

full-body naked women.f72r2 Gemini

My copy is almost illegible. I can see on the outer band one

naked nymph at 10:30, Miss Okar-Aldy, with the right arm

stretched out. That seems to be the "standard" starting

position in several other diagrams.

Most of the other nymphs have the right hand on the hip. Some

have the right arm back and down, bent or straight, but it is

questionable whether this pose is significantly different

from hand-on-hip. The extreme case is the figure at 06:30 on

the outer band, Miss (or Master?) Otarar (dressed, standing

on an horizontal tube); the first of four dressed figures.

Miss Ofchdamy, the first of the five "extra" nymphs at the top,

may be another significant exception, but her

forearm is not visible on my copy.f72r3 Cancer

The outer nymph at 11:00, miss Otchy(?)-Daiin, has the right

arm stretched back and down at 45 degrees. She may well be the

leader of that band; there is a wide gap between her and the

preceding nymph at 09:30.

I cannot see any other nymph with stretched right arm, but

half of the nymphs are just faint blurs on my copy. f72v3 Leo

I see two ladies with the right arm stretched back and down at

45 degrees, bot on the inner band: Miss Oky at 11:30,

and Miss Oteeod(?) at 06:15.

There is no obvious starting point, but the diagram is

cut by multiple creases between 07:00 and 10:30, which seems

a natural place to start.f72v2 Virgo

This seems to be a very complicated month astronomically 8-)

There are many nymphs in new and strange poses, and even a freak

reappearance of the dustbin (shallow, with "cutaway" edge).

I can see several nymphs with the right arm stretched back and

down at 45 degrees. In the outer band there are Opaiin at 08:30,

and Ofchdy-Sh. at 05:00. In the inner band we have four consecutive

nymphs starting at 05:00 (Cheosy, Ofcheey, Yteedy, On-Aiin).

However we also have a nymph at 00:15, Miss Oeedy, with *both*

arms stretched back, and hands clasped behind her. Three

nymphs (outer Oeedey and Oeeo-Daiin at 10:30-10:45, inner

Oka*** at 10:30) are grasping their stars with both hands;

and inner Okeeom at 01:30 is almost doing the same.f72v1 Libra

Miss Oteoly at 10:30 on the outer band (the "standard" starting

place), has the right arm stretched back and down. But so do

Miss Okeeoly at 01:00 and Miss Okal at 11:00.

In the inner band the nymphs are holding their right hand in

various positions near the hip; none seems to have a clearly

"stretched-out" arm. The one that comes closest is Miss Oko**y

at 03:30, but she is bending down to avoid the "cigarette

hole", and the hand position my be accidental. In any case

that hole would be a natural starting place for the inner band.f73r Scorpio

Outer Misses Dolshey and Opaiin at 08:00-09:00 have outstretched

right arms. The latter is more exhuberant and holds a bigger

star. 09:00 could be a starting place in this case.

Ladies Shekal, Okeedy and Okedal at 05:00-06:30 outer band,

have stretchde arms. They cannot be all starting points...

In the ineer band, the stretched-arm ladies are Miss Chek and

Miss Kar (not their real names, I am sure 8-) Miss Kar, by the

way, is the one who was involved in the cigarette hole affair

with Taurus girl, as reported bove.

Outside the diagram, at the top, there are Miss Chockhy and

Miss Yteeody; the latter may a full stop, hardly a start marker...f73v Sagittarus

I see only three ladies with stretched arms here. In the outer

band we have Miss Ykeody at 02:00 and Miss Okeody at 10:00; the

latter may well be the band leader. In the inner band I see only

Miss Otal at 03:00.