One of the enduring mysteries of the Voynich Manuscript’s enigmatic “Voynichese” script is that it varies. Not content with having two full-blown ‘languages’/’dialects’ (known as Currier A and Currier B), the way Voynichese ‘behaves’ on a glyph-level, word-level, line-level, paragraph-level, page-level and even section-level varies in many, many other ways (e.g. LAAFU etc).

This pervasive variability is an easy spanner to throw in the works of the kind of ‘simple [universal] explanation’ that gets periodically churned up for Voynichese – you know, mirrored High German, etc. No natural language structure could explain this variability – languages are stubbornly historical and offer students challenges on many levels, for sure, but Voynichese is just something else.

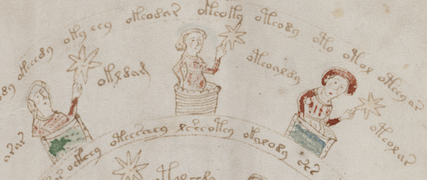

One of the many Voynichese variations is “labelese”: these are short words or phrases that appear to be attached to labels on complicated diagrams (normally with astronomical or zodiacal content, as per the dominant interpretation). Complicating the issue is that labelese can be juxtaposed with non-labelese, such as with this image from the “Aries” (f71r) page:

Here you can see some normal-looking (continuous) Voynichese (on the curved lines of text), together with some shorter labels (in EVA: okldam, oteoaldy, and oteolar). And you might possibly speculate from this that the continuous-looking Voynichese might be normal Voynichese language, and that the labelese might be some kind of simplified subset of Voynichese.

The reason for suspecting a subset is that you almost never see labelese words starting with (EVA) qo- (which is a hugely popular pattern in Currier B – so almost no qok- words or qot- words). And you often see l- initial words in some Currier B (particularly in Q13), which we can see here (but never in Currier A).

But… look again at the image. The outer band of text here runs “okeeedy oky eey okeodar okeoky oteody oto otol oteeyar“. And the inner band of text runs “ockhchy oteesaey lcheotey okarody shs“. The way that so many of these words (both in the labels and the continuous curved text) start with ok- / ot- is more than a bit suspicious, hein?

In fact, you might go so far as to suggest that labelese’s ok- words seem to broadly correspond to (say) Q20’s qok- words (I think that the labelese ok-/ot- ratio is about the same as the Q20 qok-/qot- ratio, but I haven’t checked).

In Q20, y- initial words tend to be the first words in a line (suggesting that there is some clever bastard trickery going on with line-initial glyphs), but in labelese we see very few. Perhaps labelese might be trying to disguise where each individual set of labels start?

So my thought for today is simply this: might ok- be a kind of labelese-specific null? In which case the original text might have been continuous text, which was then divided into small label-sized chunks and had an ok- prepended to most of them.

Please treat the following as mere speculation by a person lacking any competence in comparative linguistics or cryptology.

I think I’m not the only person to whom it has occurred that the glyph which EVA renders as “o” might have the sound-value “a”.

My one-cent worth in this case is that there are terms whose sound might be heard and rendered by a non-native speaker as ‘ak’ and which can refer to stars or to intellect or intelligence. If anyone feels curious about this, I’ll hunt out the source where I read it, though that might take a while. My first guess would be that I read it in terms of the Arabic [‘aql] in Nasr’s Introduction to Islamic Cosmology, or Burckhardt’s little booklet about Ibn Arabi, or Ibn Majid’s Kitāb al-Fawā’id.. or else only in relation to pre-Islamic Egypt where the term for a persons soul was ‘akh’.

Diane: plenty of people have suggested this, usually with the same basic aim – to make ‘star labels’ begin with al-. Unfortunately, like pretty much every ‘universal’ Voynich reading, this breaks down when you try to apply it elsewhere.

I probably should add that my suggestion in this post is broadly consistent with the labels here being a very much expanded / longhand / verbose cipher form of the cisiojanus mnemonic (which I’ve discussed many times on Cipher Mysteries).

i.e. something along the general lines of (for “cisiojanus epi sibi vendicat”):

ok/[cc]/[ii] — Circumcisio

ok/[ss]/[ii]

ok/[oo] — Octava Stephani

ok/[jj]/[aa] — Janus

ok/[nn]/[uu]/[ss]

ok/[ee] — Epiphani

ok/[pp]/[ii]

ok/[ss]/[ii] — sibi

ok/[bb]/[ii]

ok/[vv]/[ee]/[nn] — vendicat

ok/[dd]/[ii]

ok/[cc]/[aa]/[tt]

If these zodiac labels are (effectively) verbosely enciphered syllables within a Cisiojanus-style mnemonic, this would imply quite a lot about the distribution we should see (e.g. consonants usually on the left, vowels usually on the right, but with exceptions in both cases, particularly for longer or shorter syllables).

I’ll return to this in a future post…

What I once suspected is that ot/ok is a prefix for “Lord” or “Lady”. However, in the example page ( f71r ) this inscription is also continued in the outermost and innermost circle. This speaks against this assumption.

bi3mw: it’s a decent enough suggestion, but (like almost all Voynich ideas) it only makes sense locally. To be fair, that’s no less true of 95% of the Voynich ideas I’ve had myself. The difficulty is combining multiple ideas into something a bit more broader which you can test, which is basically what I try to do on Cipher Mysteries.

For any able to access it through JSTOR (not in my institution’s list, sadly) there’s what looks to be an interesting discussion, in a Franciscan journal, of the way the ‘cisiojanus’ mnemonic intended to help students, moved through Europe, and being altered to suit the liturgical feasts observed in different places, altered the syntactical structures and month-names…’ [from the first page preview]

William O’Sullivan, ‘An Irish cisiojanus’, Collectanea Hibernica, No. 29 (1988), pp. 7-13 (7 pages).

Gut reaction to “okeeedy oky eey okeodar okeoky oteody oto otol oteeyar“is that it looks like a declension or conjugation. Two cents.

Diane: I indeed have a Cipher Mysteries post going into this very topic:

https://ciphermysteries.com/2018/11/23/the-linguistic-diffusion-of-cisiojanus-mnemonics

I think this is the way forward. You can look at the star labels and some differ by one character. It makes no sense to look for a cipher here. Perhaps it’s a very early form of a hash system, where normal words, phrases or sentences are squashed down to a labelese word, in a many to one relationship.

Hard to decide for sure, but can be done given enough patience.

Nick,

Of course – once again, I should have *begun* by doing a CM search.

Always impressed by specialists abilities when it comes to provenancing breviaries by their regional variants on the liturgical calendar, I’m staggered to think of how much work is implied here. First, get the transcription values right; then re-hydrate the mnemonic; then identify the language, and finally identify the local roster for this this particular cisiojanus (supposing it one) was devised. But if it can be done, and proves true, it will be a huge assist to provenancing.

All the best.

Nick, assume a text written as variables e. g. (a1)(a2)(a3)(a4)(a2)(a3)(space)(a5)(a1)(a1)… sufficiently long, so we must utilize our entire alphabet when we replace these variables with concrete plaintext letters, such as e. g. -> bcrwcr zbb… How many possible permutations do we have? Simply n! (factorial) when our alphabet has n different letters. Now, let’s add one more letter, because ‘b’ might not always be a ‘b,’ but could be a similar yet different letter, say a ‘v’. Our text could then be -> bcrwcr zvb… Thus, we have (n+1)! possible permutations for all substitutions now. The difference is (n+1)! – n! = n!*n permutations.

We can’t exclude anything as we are still uncertain about the plaintext language. When we increase our alphabet from, for example, 20 to 21 different glyphs/letters, we gain additional 48.658.040.163.532.800.000 possible permutations. That only if we can consistently distinguish between ‘b’ and ‘v.’ If not, assuming both possibilities on uncertain places, we get even more possible permutations for investigation. Now, we do statistics based on a 20-letters alphabet. Are we capable to recognize a plaintext language consisting of 21-letters? The number of potential additional patterns exceeds 48.658.040.163.532.800.000. I can’t imagine! But some people perceive different dialects of the hypothetical 20-letter based language. Only, this language has nothing to do with our 21-letters plaintext… Now, imagine not just one letter difference, but ten letters! Statistics based on a 20-letter alphabet become useless for further plaintext recognition. Sorry, making something an axiom that is not leads nowhere.

Let me give you a concrete example from the “labeleses” (is it one according to definition?). On page 70r, in the outer ring, there are seemingly 9 consecutive ‘o’s followed by an “awareness ribbon” glyph and two others. According to EVA it must be a pure decoration. What else should it be – 9 x ‘o’? However, if we acknowledge a difference among the ‘o’s – some open at the top, some not – we include an additional glyph. Assuming these are two separate glyphs, and using my key, we can match this to a valid sentence in the plaintext (naturally, the scribes play here with words to combine the glyphs this way omitting other glyphs). It says:

אֵתָם שׁוֹא בּוֹא גֵּא גַּב אוֹ גֵּב בַּג

Devastation/ruin to be burned up will come upon proud bulwarks/breastworks/boss (convex projection of shields) and/then (become) a den (of lions) (or locusts’) spoil/booty