It’s well-known that the distribution of Voynichese page-initial (and indeed paragraph-initial) glyphs is, unlike the rest of the text, strongly dominated by gallows characters. But what is less widely known is that something really fishy is going on with the distribution of all the other line-initial glyphs too.

As far as I know, nobody has yet given this behaviour the in-depth attention it properly deserves, which is why I think it would make a good subject for a paper. Though it perhaps needs a catchier name than “Line-Initial But Not Paragraph-Initial Glyph” (LIBNPIG) statistics (so please feel free to come up with a better name or acronym).

Though you might reasonably ask: isn’t this just another side of the whole constellation of LAAFU (“line as a functional unit”) behaviours?

Well, yes and no. “LAAFU” is a shorthand mainly used by some Voynich researchers to signal their despair at the unknowableness of why certain glyphs seem to ‘prefer’ different positions within a line. So yes, LIBNPIG behaviour is a kind of LAAFU behaviour: but no, that doesn’t mean it can’t be understood. (Or at least carefully quantified and tortured on a statistical rack.)

LIBNPIG Observations

How do we know that something funky is going on with LIBNPIGs?

LIBNPIG ‘tells’ are perhaps most visible in Q20 (Quire #20). For example, even though EVA daiin is common in Currier A pages (you may recall that it’s one of the ‘Big Three’ A-words – daiin / chol / chor), it’s far less common in Currier B pages: however, when it does occur in Q20, it is frequently in a LIBNPIG position. In fact, this is true of all word-initial EVA d- words in Q20, which you can see here (scroll to the bottom).

Similarly, if you look at EVA s- words (ignoring sh- words, which is a particularly annoying EVA artifact, *sigh*) in Q20, you should also see that these appear far more often line-initially than they should.

Is that all? No. The same is true of EVA y- words in Q20 too, but this pattern is additionally true in Herbal B pages. Note that this also seems to be true of some Herbal A pages, but EVA y- words in Herbal A appear to work quite differently to my eyes. (Though I’d advise looking for yourself, & form your own opinion.)

Curiously, even though paragraph-initial words so strongly favour gallows characters, LIBNPIG words seem to abhor gallows characters, a behaviour which is in itself quite suggestive and/or mysterious.

Conversely, if you go looking for LIBNPIG EVA ch- and sh- words, I believe you’re far more likely to instead find them clustering at the second word on a line. Note that Emma May Smith (with Marco Ponzi) looked at this back in 2017, though more from a word-based perspective (even though the first two words on a line in Q20 are often fairly odd-looking). The concern for me is more that these behaviours mean that Voynich word dictionaries (and indeed all word analyses) based on line-initial words are unreliable.

So, what is going on in Q20 (in particular) that is making LIBNPIG words prefer d- / s- / y- so much? I guess this really is the starting point of the paper I’m suggesting here.

Vertical keys?

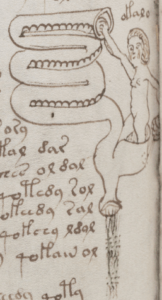

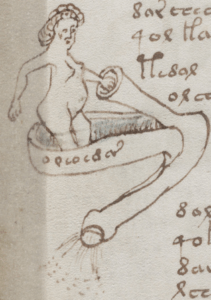

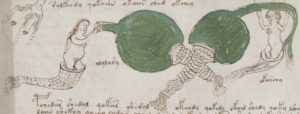

The notion that the first column of glyphs might have some kind of special meaning is far from new. In fact, there is evidence suggesting this in the manuscript itself on page f66r, where you can clearly see a column of glyphs (though admittedly there is also a column of freestanding words to its left). This is a curious item to find in a manuscript.

But might all (or, at least, many) pages of Voynichese text contain vertical keys inserted as a single line-initial glyph at the start of lines? Philip Neal speculated about this possibility many years ago, causing me to (occasionally) refer to these as “vertical Neal keys”. A vertical key might conceivably be used for many things, such as inserting an (enciphered) page title, or even a folio number or page number: though it’s easy to argue that the relatively narrow range of glyphs we see appearing here probably rule this out.

In “The Curse of the Voynich” (2006), I speculated instead that a glyph inserted at the start of a line might form part of some kind of transposition cipher. The suggestion there was that a second glyph (say, a k-gallows) might act as a token to use the glyph (or some function of that glyph) inserted at the start of the same line. This would be a fairly simple crypto ‘hack’ that would make codebreakers’ jobs difficult.

There are many other possible accounts one can devise. For example, it’s possible that the first glyph on a non-paragraph-initial might function as a kind of catchword, to link the end of one line with the start of the next. Alternatively, it might be telling the reader how to join the text at the end of the preceding line with the text at the start of the current line. Or it might have some kind of crypto token function (e.g. selecting a dictionary). Or it might be a numbering scheme. Or it might be a marker for some funky line transposition scheme. Or a null. Or… one of a hundred other things (if not more).

If all these speculations seem somewhat ungrounded, it’s almost certainly because the basic groundwork to build a sensible discussion of LIBNPIG behaviour upon hasn’t yet been done. Which is your job. 🙂

LIBNPIG Groundwork

What needs doing? For a start, you’d need to build up a solid statistical comparison of paragraph-initial glyphs and LIBNPIG glyphs, along with paragraph-second glyphs and LSBNPS (line-second-but-not-paragraph-second) glyphs, for paragraph text in each of Herbal A, Herbal B, Q13 and Q20 (I would suggest).

With those results in hand, there are some basic hypotheses you might want to try testing:

- Is there any statistical correlation between a LIBNPIG glyph and the glyph immediately following it? Oddly, it seems that nobody has yet tried to test this – yet if there isn’t (as visually seems to be the case), then I think it’s safe to say that something is provably wrong with all naive text readings.

- Is there a correlation between a LIBNPIG glyph and the previous line’s end-glyph?

- Is there a correlation between a LIBNPIG glyph and the following word’s start glyph?

- Do paragraph-initial second words behave the same way as LIBNPIG second words?

- Might LIBNPIG glyphs simply be nulls? Might they be chosen just to look nice? Or do they have some genuinely meaningful content?

- How does all this work for paragraph text in each of the major sections of the Voynich Manuscript? e.g. Herbal A, Herbal B, Q13, Q20

- (I’m sure you can devise plenty of your own hypotheses here!)

Ultimately, what we would like to know is what LIBNPIG behaviours tell us about how the start of Voynichese lines have to be parsed – for if there is no statistical correlation between a line-initial glyph and the glyph following it, this cannot be a language behaviour.

Even though we can all see numerous LAAFU behaviours, it seems that few Voynich researchers have yet accepted them solidly enough to affect the way they actually think about Voynichese. But perhaps it is time that this changed: and perhaps LIBNPIG will be the thing that causes them to change how they think.