“Jack and the Cursed Manuscript” – Part One

1. MEDIEVAL HOVEL

(THOUGH AS THE LIGHTS COME UP, IT INCREASINGLY RESEMBLES A MODERN-DAY CRACK DEN)

JACK’S MUM: Woe is me! I’m a poor old peasant woman ‘oo ‘as frittered a giant’s castle full o’ gold on online casinos an’ Class A drugs.

JACK [aside to the audience]: You’d have thought it might have lasted longer than a week.

JACK’S MUM: Tell me, my darlin’ Jack, does we ‘ave anyfink in the world left ter sell?

JACK: Only the cow you won in a virtual meat raffle, the one you called “Meteor”.

METEOR: Moo.

JACK’S MUM [aside to the audience]: Face it, you can’t get Meteor than a cow. [badum-tshhh]

JACK: I’ll take her to market, I’m bound to see some more magic beans there. I’m on a lucky streak, got the Midas touch, I have.

JACK’S MUM [aside to the audience]: Don’t ‘e take after me? Ooh, I couldn’t be prouder!

2. TOWN SQUARE

TOWN CRYER: Young fellow!

JACK: Errrm… [looks around] do you mean me?

TOWN CRYER: The very same! The young man unwillingly taking his cow to market, just like Rick Astley and his sheep.

JACK: Rick Astley?

TOWN CRYER: It’s how he got rich, you know. “Never gonna give ewe up, never gonna let ewe down”.

METEOR: Moo.

TOWN CRYER: Exactly. And not at all like that idiot lad Jack who swapped his cow for magic beans and killed the giant.

JACK: Errrm… “idiot lad”?

TOWN CRYER: Even as we speak, insurance company agents are combing the land to track him down and bring him to justice.

JACK [backing away]: I’d… best be going, I think.

3. MEDIEVAL MARKET

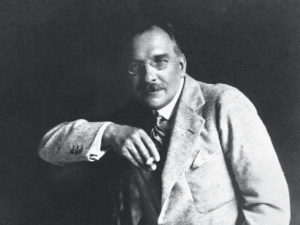

JACK APPROACHES A BOOKSELLER WITH A MOUSTACHE AND TWINKLING EYES.

JACK: Excuse me, sir, but have you seen a curious traveller? He was right here last week, selling m-m-m-mysterious beans. Definitely not magic ones, anyway.

WILFRID: He’s been and gone. [badum-tshhh]

JACK: Oh no! So what priceless MacGuffin will I exchange our possessions for this week?

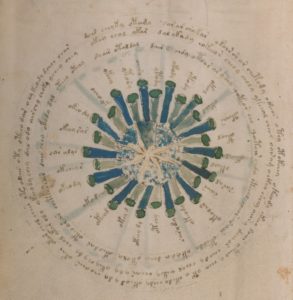

WILFRID: I have just the thing for you. [He brandishes the Voynich Manuscript] Behold – the world’s most unreadable manuscript! And it even has a blank price tag!

JACK: That’s my kind of price tag.

WILFRID: …because you’re insanely rich?

JACK: No, because I’m innumerate.

WILFRID: Errrm… so how much do you actually have to spend?

JACK: Basically, this cow.

METEOR: Moo.

WILFRID: Well… this manuscript’s proper price should be ten cows, but I’d accept one cow now with another nine in the future if you become unexpectedly filthy rich.

JACK: No, no, I had that last week: a guy selling magic geese here also wanted a down payment.

WILFRID [rolls eyes]: OK, just one cow for the manuscript, then.

JACK: A pleasure to do business with you, Mister. [Takes book and hands him cow’s lead]

WILFRID [aside to audience]: Why should I care? Now I’ve seen one, I can hoax as many as I like. Ethel will be delighted!

4. BACK AT THE HOVEL

JACK: I’m back, mum!

JACK’S MUM: So what did you get for dear old Meteor, then? More magic beans?

JACK: No, something much better. I give you – The World’s Most Unreadable Manuscript! [He triumphantly holds the book aloft]

JACK’S MUM: Errrm… [awkward pause] more unreadable than Article 57? And every footballer’s memoirs ever written?

JACK: At least 10% more unreadable than those, yes.

JACK’S MUM: So… what’s it about?

JACK [rolls eyes, passes the book to his mother]: It’s not about anything, it’s unreadable. Even the pictures aren’t about anything, they’re unreadable too.

JACK’S MUM: Well, that is a novelty. [Puts on airs and graces voice] One shall have to run one’s new acquisition past one’s dear friends next door.

JACK [encourages audience to join in]: Oh, No We Won’t!

JACK’S MUM: Oh, Yes, We Will. Dame Trot and Prince Salerno know all about ‘erbal medicine. They’re bound to be able to broaden your young scope.

JACK [muttering under his breath]: So I’ve heard, so I’ve heard.

JACK’S MUM: Come, young Jack. Take one’s arm as one perambulates to one’s neighbour’s esteemed location.

JACK: Whatevs, Mama. [shakes head silently]

5. AT DAME TROT’S CAMP MANSION

DAME TROT [opening the door]: How fantabulosa, it’s my bona omi young Jack! And his shyckled palone Margaret. [calls upstairs] Princey, off the khazi, visitors at front of ‘ouse.

JACK’S MUM: So delayted to see, you, may dear Dame Trot.

JACK: But… she’s a man?

DAME TROT: I’ll have none of that lingua in my flowery, young omi. Again in Polari, please.

JACK: But… Palone Trot is an omi?

DAME TROT [aside to the audience]: I don’t think the poor chicken knows he’s in a panto! [To Jack, somewhat condescendingly] Oh, it’s an old tradition in these parts.

JACK: But… your riah isn’t zhooshed like a palone, and you haven’t even got fake willets. What kind of a panto Dame are you?

DAME TROT [aghast]: Why, according to Charles Singer’s (1928) “From Magic to Science”, Dame Trot was a made-up female practitioner based on an entirely male medical tradition.

JACK: So you’re a Dame only in name?

DAME TROT: Precisely. You can’t just camp up your crypto to get onto Cipher Mysteries, these days you have to play by the ‘istorical rule book.

PRINCE SALERNO [emerging from inside the house]: Bona journo, everyone. What brings you here this bona morning?

JACK’S MUM: One has a mysterious book to show you both. [She extracts the Voynich Manuscript from her capacious handbag]

PRINCE SALERNO [visibly shocked and appalled]: Kiss my quongs and slap my town-hall drape, it is The Cursed Book that she has!

DAME TROT: What, Katie Price’s fifth autobiography?

PRINCE SALERNO: Nay, nay, 10% worse still – it is the book that has no beginning and no end.

DAME TROT: That still sounds like “Love, Lipstick and Lies”

PRINCE SALERNO: Jest not!

DAME TROT: I jest did.

PRINCE SALERNO: Margaret and Jack, to free yourself from this terrible curse, you must now climb Mount Doom and hurl the book deep into the biggest Crack you can find.

JACK’S MUM: Oh. Is there not time for a cup of Earl Grey before one goes?

PRINCE SALERNO [glowers even more powerfully]: No. When destiny raises its head, you must grasp it firmly with both hands.

DAME TROT: Definitely both hands.

PRINCE SALERNO: Go now, and remember the ancient wisdom of the Masons – the bigger the Crack, the better the builder. Fare thee well!

[TO BE CONTINUED…]